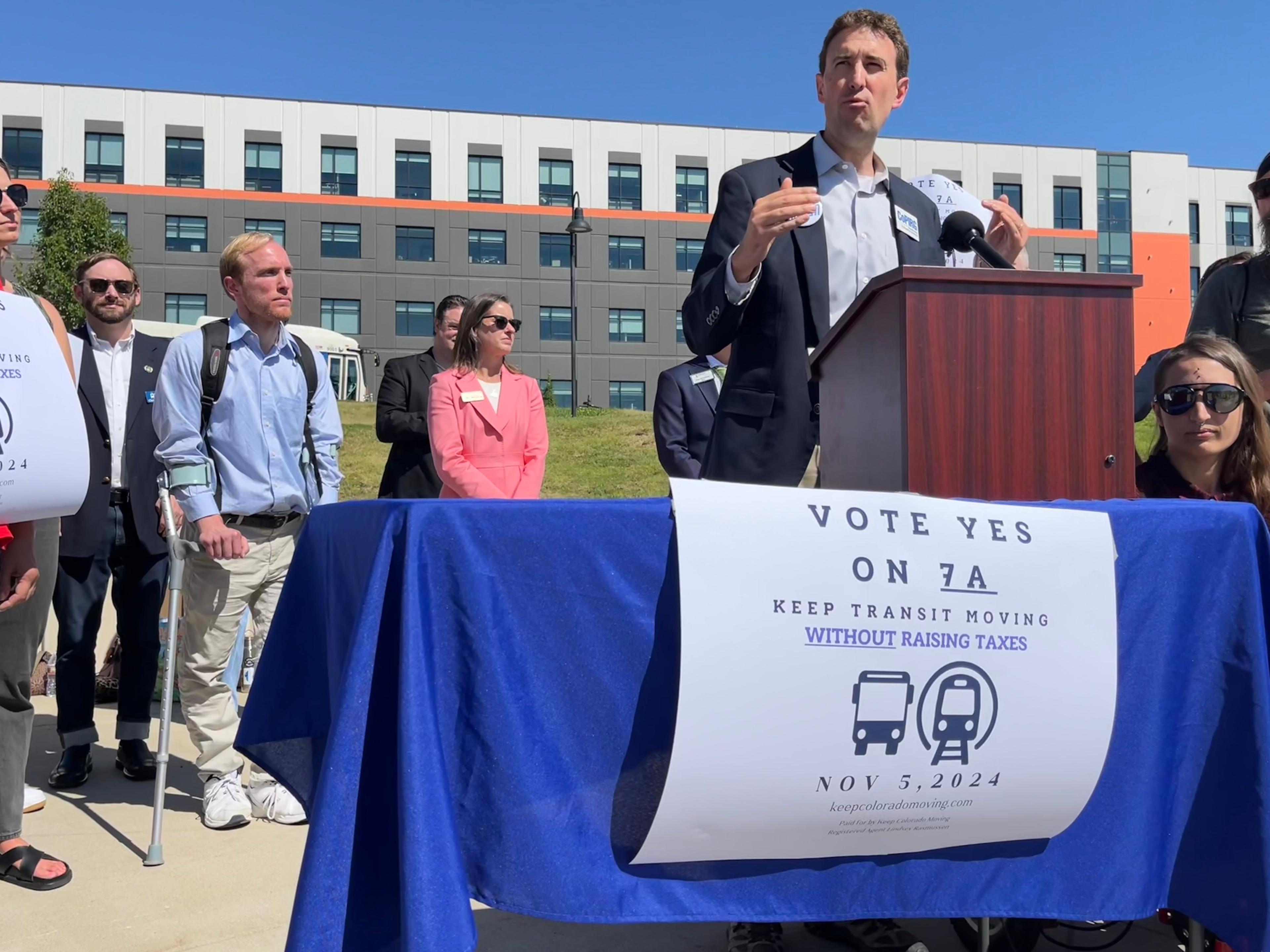

Dozens of transit advocates and local elected officials — including members of the Regional Transportation District’s own board of directors — gathered Friday morning to officially launch a campaign that seeks to permanently allow RTD to keep money that would otherwise be returned to taxpayers.

If Question 7A on the November 2024 ballot fails, about $670 million, or half of RTD’s annual revenue, would be subject to revenue limits set by the Colorado Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights. That could mean cuts to transit service, proponents warned.

“If voters don't take action this fall, then RTD, our major transit agency, will see a cut in how much money they're able to put into our core system,” said Danny Katz, director of the Colorado Public Interest Research Group, part of the coalition backing the “Keep Colorado Moving” campaign.

“That's the exact opposite direction that we should be going,” he added. “Without raising taxes, we can keep transit moving if voters vote yes on 7A.”

RTD officials said it’s difficult to estimate how much revenue would be returned to voters in the future, but they have estimated that the agency would have refunded $650 million between 2007 and 2019 if TABOR restrictions were in place then.

Representatives from the Boulder Chamber of Commerce, the Denver Streets Partnership, the Metro Mayors Caucus, AARP Colorado, the Colorado Cross-Disability Coalition, the Southwest Energy Efficiency Project, and other community groups all attended the campaign launch at an RTD rail station on Denver’s west side. Dozens of other groups have also endorsed the campaign.

Early polling suggested big support for the measure. But it’s been a tough few months for RTD

Polling presented to the RTD board in May showed nearly 70 percent support for the ballot measure among respondents. And so-called “debrucing” efforts, a reference to TABOR’s author Douglas Bruce, are successful more than 80 percent of the time.

But RTD has had a long, difficult summer — especially on its light rail network. A handful of maintenance projects, including one that came as an apparent surprise, have disrupted service significantly and left riders stranded at hot train stations.

The agency’s highly-paid chief of police, who was tasked with improving safety and security on the system, was placed on leave this summer. CPR News later reported that he routinely drove an agency vehicle at more than 100 mph and did not access RTD facilities very often.

RTD has also struggled to restore service slashed during the pandemic and only recently has said it is making enough progress in hiring drivers and other front-line staff that it can begin to plan to do so.

Asked whether such issues may complicate the ballot measure campaign, Littleton Mayor Kyle Schlachter acknowledged they were real.

“But the simple answer is less money isn’t going to solve these issues,” he said. “That’s basically the question with 7A: Do we want RTD to have less money? We certainly don’t. That’s why I’m voting yes.”

Proponents said repeatedly that the measure won’t raise taxes. One person with relevant expertise said they need to be more specific

Miller Hudson, a former state legislator, ran a campaign in the mid-1990s that asked voters to debruce RTD for 10 years. An earlier attempt failed in 1994, Hudson said, but his effort was successful because they were specific with voters about the measure’s cost and benefits.

“If voters don't feel that they understand precisely how much they're going to pay and where it's going to be spent, you're probably not going to win,” Hudson said.

The 7A proponents “ducked the difficult questions” at their announcement, Hudson said. Former RTD director Natalie Menten, a Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights advocate, asked the group whether voters would be giving up their TABOR refunds and what the average taxpayer pays in RTD sales taxes in a given year.

Katz, who was leading the press conference, replied with a “yes” to the first question before emphasizing the benefits of a successful ballot measure for RTD. He didn’t have an answer to the second question.

RTD’s own research said that its funding per capita is $372; the agency hasn’t yet replied to a request for how much of that would be subject to TABOR and potentially refunded to the average taxpayer.

Menten believes TABOR acts as a “24/7 watchdog” on RTD and if voters were to remove its limits permanently, they would effectively abolish that.

“I’m concerned about that,” she said. “It's creating a blank check for a public agency in control of a tremendous amount of money.”

But voters will have to decide whether the prospect of being refunded an as-of-yet unknown fraction of $372 would be worth it for a probable decrease in transit service.

Two transit riders told CPR News it wouldn’t. Maria Guadalupe Zapata, an elderly southwest Denver resident who uses RTD’s services regularly, said she can’t walk or see well and relies on public transit to attend church, get to the food bank and travel to appointments around the city.

“I don’t think the refund would be a lot,” she said through an interpreter.

Dominic Holloway, a Lakewood resident who said he’s used the W Line a lot recently since his car broke down, said he’d probably lose his job if it were to be cut. The possibility of a refund just isn’t that tempting, he said.

“I’d rather have the service,” he said.

- Records show RTD chief of police, now under investigation, routinely drove agency vehicle over 100 mph

- RTD is planning to expand its services in 2025 after years of stagnation

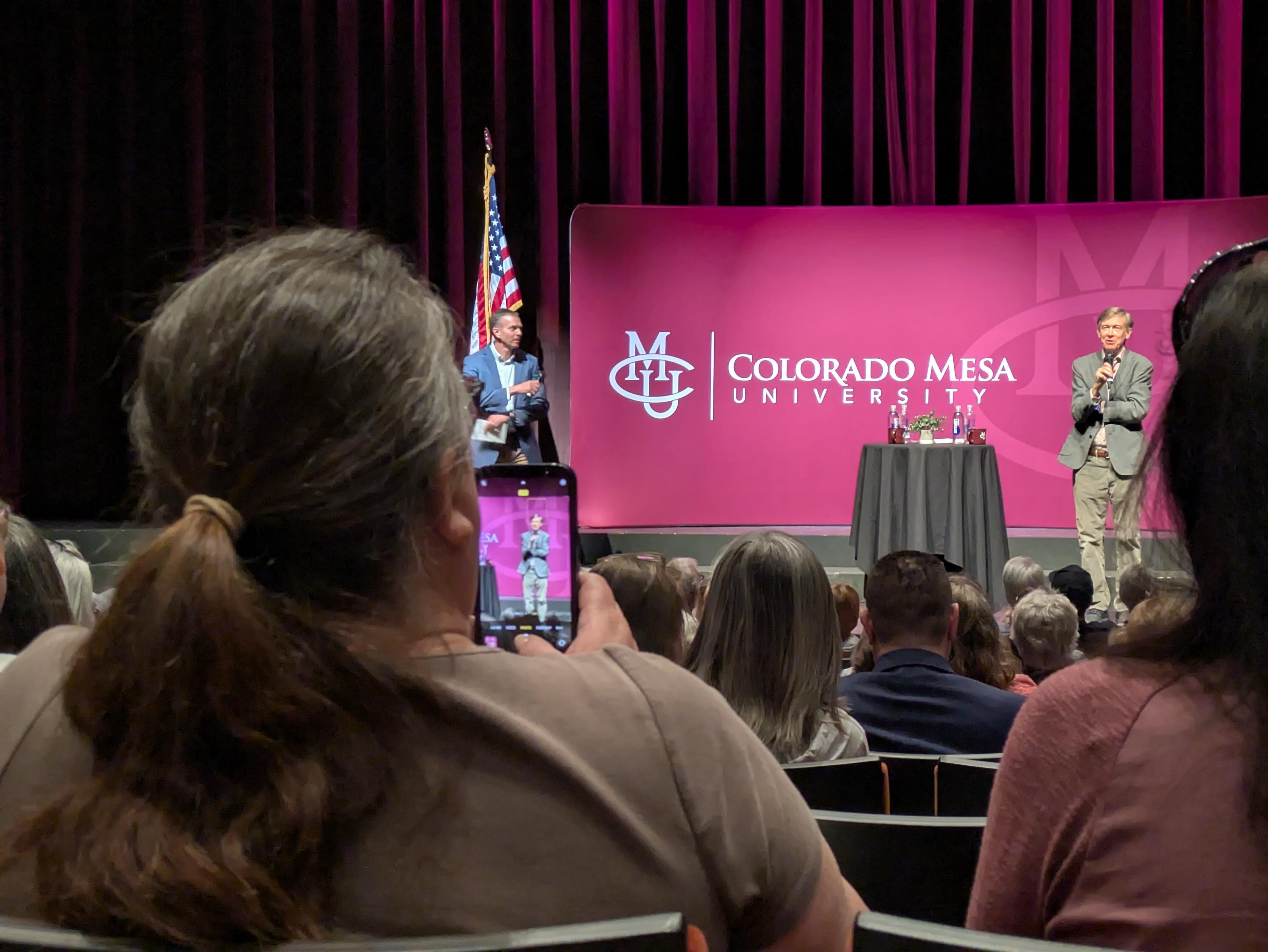

- Gov. Jared Polis plans to take a sharper interest in this fall’s RTD board elections

- More RTD reform is coming next year, Colorado legislators say