Restaurant owner Edwin Zoe learned to love electric cooking by shopping for his first employee: his mom.

After Zoe’s father died, his mom moved from Taiwan to live closer to her son in Colorado. To avoid becoming the focus of her furious work ethic, Zoe opened a small restaurant in 2010 where she could cook traditional Taiwanese dishes. He named the Boulder restaurant Zoe Ma Ma and started sourcing kitchen equipment.

“Having a technology background, I knew about induction ranges, which offer safety, comfort and efficiency — all things I wanted for my mom,” Zoe said.

Induction cooktops use electromagnetic fields to generate heat inside a pot or pan. Since there’s no open flame or red-hot coil, induction appliances keep commercial kitchens cooler and make cleanup as simple as a few wipes with a rag.

Zoe’s embrace of electric cooking puts him at odds with the larger restaurant industry, which has a deep affection for natural gas built through decades of practice, marketing and famous chefs proving their mettle over an open flame. A 2022 survey published by the National Restaurant Association found more than 75 percent of restaurants across the U.S. rely on fossil fuels in some capacity.

The reign of natural gas, however, faces a new challenge from cities trying to regulate fossil fuels out of buildings to cut their climate-warming emissions and improve indoor air quality. Electric equipment is also getting cheaper and more automated, offering restaurants an option to calm and cool often frantic kitchen spaces.

Those developments have left chefs — an influential group tasked with satisfying their customers and their bottom lines — to pick a side in a red-hot climate battle: electricity or gas.

Cities vs. the restaurant industry

Denver offers a clear example of the growing conflict between restaurants and climate-minded communities.

In the last few years, the city has approved building codes and energy-efficiency regulations designed to nudge buildings away from natural gas stoves and furnaces in favor of all-electric alternatives.

Policymakers hope the shift will allow commercial and apartment buildings — the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in Denver and many other large cities — to tap into an energy grid increasingly powered by zero-carbon sources like wind and solar. Multiple studies have also shown that gas stoves produce pollutants linked to respiratory illnesses like asthma.

Denver’s pro-electrification building codes address gas furnaces and water heaters, not gas stoves or other cooking equipment. The city is nevertheless facing a federal lawsuit from the Colorado Restaurant Association, which warns that small mom-and-pop operations could face higher costs as their landlords shift to electric heating and try to improve overall energy efficiency. Trade groups representing the propane industry and homebuilders have also signed onto the case.

“It’s not that we’re against making this transition,” said Colin Larson, the policy director of the Colorado Restaurant Association. “It’s just that we have not seen any of these public policy proposals recognize the costs that are being foisted on small businesses.”

A similar lawsuit filed by California restaurants scuttled the nation’s first ban on gas hookups in Berkeley, Calif. Other jurisdictions like Los Angeles and New York have exempted restaurants from rules limiting natural gas in new and existing buildings.

Denver is fighting the lawsuit, but the city has also hired former chef Andrew Forlines to make a case for a climate-friendly, electrified future directly to restaurants. He now works as an electric cooking administrator for the city’s climate office.

Forlines said his industry has romanticized the image of a tattooed chef toiling over an open flame. While he thinks the stereotype has its place, he’s convinced that many chefs would appreciate a new generation of high-precision electric cooking gear, especially if it’s offered at the right price.

That’s why Forlines is now gathering input for a city-run electric equipment rebate program. Pennsylvania has already launched incentives to nudge restaurants toward electric cooking.

“We're not going to force anyone to do anything. We're going to find the opportunities where they are,” Forlines said.

A tricky decision for small restaurants

Jeremy and Darren Song are two restaurant owners facing a choice between electricity and gas.

Last spring, the brothers and business partners shuttered Turtle Boat - Colorado Poki Salads, an award-winning restaurant in south Denver, to hunt for a larger location. The pair thinks electric cooking might match their environmental values and offer a comfortable kitchen to help retain staff, but they worry about the cost.

“We’re just doing our due diligence, trying to go around and see people who have it in action,” said Darren Song, who manages the restaurant business.

Their curiosity about electric cooking brought the brothers to a demonstration at Dragonfly Noodle, one of Zoe’s ramen shops in downtown Denver. While his mom is now mostly retired, induction burners pack the kitchens of two Zoe Ma Ma locations in Denver and Boulder, plus another ramen operation in Boulder.

Before the restaurant opened to serve hungry office workers, Zoe put a quarter cup of water atop one of the burners and boiled it in seconds. “That’s extremely fast,” Zoe bragged. “It’s faster than gas.”

The Song brothers had a lot of questions for Zoe. Yes, he told the brothers induction ranges cost more than standard gas equipment upfront, but the price gap is narrowing every year. Yes, the cooktops offer precise temperature control that is dialed in through a digital input. Yes, there are bowl-shaped induction burners built for Asian-style wok cooking.

While natural gas tends to cost less per unit of energy than electricity, Zoe told the Songs the comparison doesn’t factor in the efficiency of induction cooking. Almost all the energy drawn by the electric ranges heats food rather than the kitchen space. The difference means his business spends less on air conditioning, and his staff doesn’t sweat through their shifts.

“You could long-term end up saving yourself a lot of headache and heartache by retaining staff,” Zoe told the Song brothers.

Despite Zoe’s faith in electric appliances, his ramen shop still has one natural gas burner below a massive pot of broth. While he would love to electrify the final piece of equipment, he hasn’t found an electric model capable of keeping 20 to 30 gallons of liquid simmering for hours.

Kitchens for a low-carbon future

The ramen shop is far from the only commercial kitchen with a ravenous hunger for energy.

A 2018 survey by the U.S. Energy Information Administration found food service uses more energy per square foot than any other type of commercial space, including retail shops, healthcare clinics or offices.

Natural gas offers chefs a reliable way to deliver large amounts of energy for stoves and fryers. The steady fuel supply frees up their electrical panels to handle walk-in fridges and other appliances. If cities limit access to fuel, restaurant and natural gas groups warn small shops could end up paying thousands to upgrade kitchen hardware and electrical wiring.

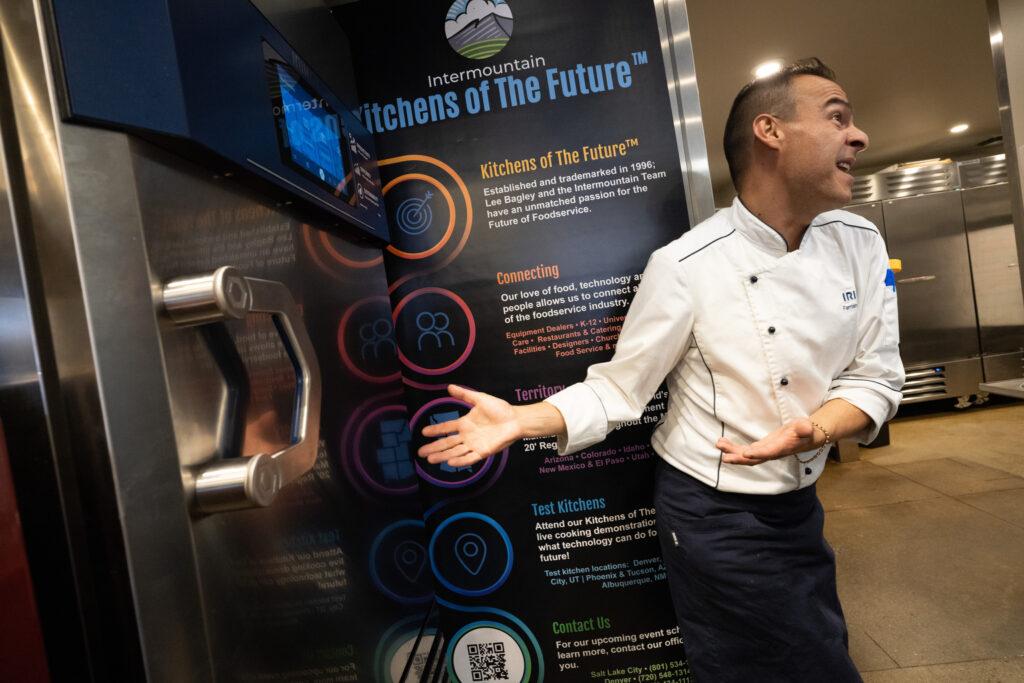

While high energy demands have helped make gas nearly standard in commercial kitchens, a new generation of efficient, all-electric equipment could shift the equation. To see some examples in action, Jeremy and Darren Song recently visited an equipment demonstration called Kitchens of the Future organized by Intermountain Food Equipment, a local appliance retailer.

That’s where a sales representative for Rational, a German equipment manufacturer, showed off his company’s iCombi oven, which applies steam and convection heat in an automated sequence to cook three types of taco meats. While the machine in the demonstration space was gas-powered, the company offers an identical electric version.

Darren Song bit into a steak taco and was blown away by the results. Jeremy Song, the head chef for Turtle Boat, talked about how the machine could help make his future staff more creative by automating more mundane tasks in the kitchen.

The brothers left the demonstration interested in all-electric equipment, but not primarily for environmental reasons. Based on all their research, making the switch away from natural gas seems like a good move to support their team and build a menu with consistent and creative dishes.

The Songs won’t make a final decision until they find a bigger space for their restaurant. In the meantime, they hope Denver doesn’t force them to avoid gas appliances but instead adopts a flexible approach that supports small, minority-owned businesses.

“Any restaurant is going to be operating on razor-thin margins,” Darren Song said. “If you can be enticed and aided into affecting change — those policies have always made more sense to us from a sustainability standpoint.”

Editor's note: This story has been updated to clarify that Denver's building codes don't address gas stoves or other cooking equipment.