By Philip Randazzo, Haiyi Bi and Akanksha Goyal/Boston University and the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at the University of Maryland Boston University and the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at the University of Maryland

They are the U.S. House’s frequent fliers — representatives who have traveled the country and the world on official business paid for by private interest groups. Over the past decade, they have accepted nearly $4.3 million for airfare, lodging, meals and other travel expenses.

Almost one-third of those payments — just over $1.4 million — covered the costs for a lawmaker’s relative to join the trip.

From European enclaves such as Rome, Geneva and Copenhagen to oceanfront golf resorts on both American coasts, to Asia and Africa, the trips allow members and their families to stay in world-class resorts, spend days soaking up the culture and score reservations at the hottest restaurants in town.

Critics maintain the trips — paid for by nearly 200 advocacy organizations, nonprofits, and liberal and conservative think tanks — are no more than “influence-peddling vacations.”

Since 2012, hundreds of House members, closely split along party lines, and their staff, have taken at least 17,000 privately funded trips, congressional records show.

But a five-month investigation by Boston University and the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at the University of Maryland reveals how dozens of lawmakers legally turn the trips into free family adventures. The investigation examined 628 privately sponsored trips taken by lawmakers who topped the list of “frequent fliers” in the House in the past decade.

U.S. Rep. Barbara Lee, D-California, leads the list of frequent fliers with 45 trips since 2012. Lee has brought her grandson, spouse, sister, two daughters-in-law and two children on trips to Beijing, Berlin, two locales in Africa, as well as Istanbul, Israel and other destinations — with the family always flying business class and staying in five-star accommodations.

Lee declined interview requests. In an email, her spokesperson wrote, in part: “Congresswoman Lee has been in complete compliance with Ethics guidelines when traveling on privately funded official trips. As the Ranking Member of the House Appropriations subcommittee on State and Foreign Operations, these trips provide her an important opportunity to engage on foreign policy matters that inform her committee work and her work on behalf of her district and constituents.

“As one of the few Black lawmakers in these influential positions on foreign policy, she takes very seriously every opportunity she can to improve her understanding of global peace and security policy. Her legislative record speaks to that.”

The 24 House members who travel most frequently on the private sponsor dime took either their spouse, grandchild, sister, daughter-in-law or child with them on nearly 44% of their trips, congressional records show. House ethics rules permit funders to pay for one relative to join a trip.

“It seems like an egregious abuse,” said Beth A. Rosenson, a political science professor at the University of Florida and author of a 2009 congressional private travel study.

Allowing sponsors to pay for relatives to travel, Rosenson said, undercuts the sweeping 2007 House ethics reforms intended to distance lawmakers from special interest influence on trips, and insert more transparency into the process.

Some interest groups include lobbyists on their boards or accept money from foreign governments. When they pay the relatives’ trip costs, it heightens risks that lawmakers will feel indebted to those paying the big bills, Rosenson said.

“The member is not going to forget that the group paid for them and their spouse to go to Copenhagen, which I think is a huge problem,” Rosenson said. “It goes against the professed intent of the law, which is to reduce the influence that special interest groups have on members.”

The reforms, prompted by a 2006 scandal ensnaring public officials who took extravagant free trips from prominent Washington, D.C., lobbyist Jack Abramoff, resulted in stricter limits on lobbyists’ roles in private trips. For House leaders to approve trips, details on who pays, who goes, all expected costs and an hour-by-hour daily itinerary must be disclosed in advance. Members must participate in a full day of official programming per day on trips, and are generally expected to personally pay for recreational activities and entertainment not considered “official programming” under House travel rules.

House leaders have approved dozens of trip itineraries clearly listing recreational and entertainment activities. Trip disclosure records rarely indicate whether the sponsor or lawmaker pays for the leisure activities. The itineraries show that, in addition to the trip’s official purpose — such as a conference, policy summit or meeting with business or government leaders — opportunities for travelers include fishing, golfing, sightseeing, shopping, riverboat cruises, ceramic painting, museum and art gallery visits, hip-hop concerts, sunrise yoga and even an afternoon ballgame at Yankee Stadium.

Trip records also show the members’ relatives are rarely, if ever, part of official programs. That contrasts with federal executive branch spousal travel regulations, which require spouses to participate in formal events for funding to be approved.

House rules allow the travel, in part, so lawmakers can experience firsthand the challenges facing areas of the U.S. and the world, and enable Congress to better legislate, invest in, regulate and devise foreign policy for those regions.

Few of the 628 trips the frequent House travelers took were to impoverished regions or global trouble-spots, records show.

“These trips are not to problematic areas like Afghanistan or Iraq but usually to some sort of wonderful vacation spot like Paris or Brussels,” said congressional ethics expert Craig Holman of the nonprofit watchdog group Public Citizen. “It is little more than a vacation designed to endear the member of Congress to whoever is paying for the trip.”

Some of the House members traveling frequently take a relative on nearly every trip, even local ones to Virginia or Maryland, trip records show.

Sponsors spent nearly $100,000 for Washington Democrat Rick Larsen’s wife, Tiia Karlén, to accompany him on 19 of his 24 trips since 2012, including $12,607.76 for a 2022 excursion to Madrid, trip records show.

In an emailed statement, Larsen wrote, in part: “Private nonprofit groups regularly invite members on approved trips. I am no exception to those invites. If the work is relevant to my district, my committee, or an issue where I am developing an expertise and time permits, I consider going. Then, if, and only if, the House Ethics Committee approves the travel consistent with the House Rules, will I participate in the trip.”

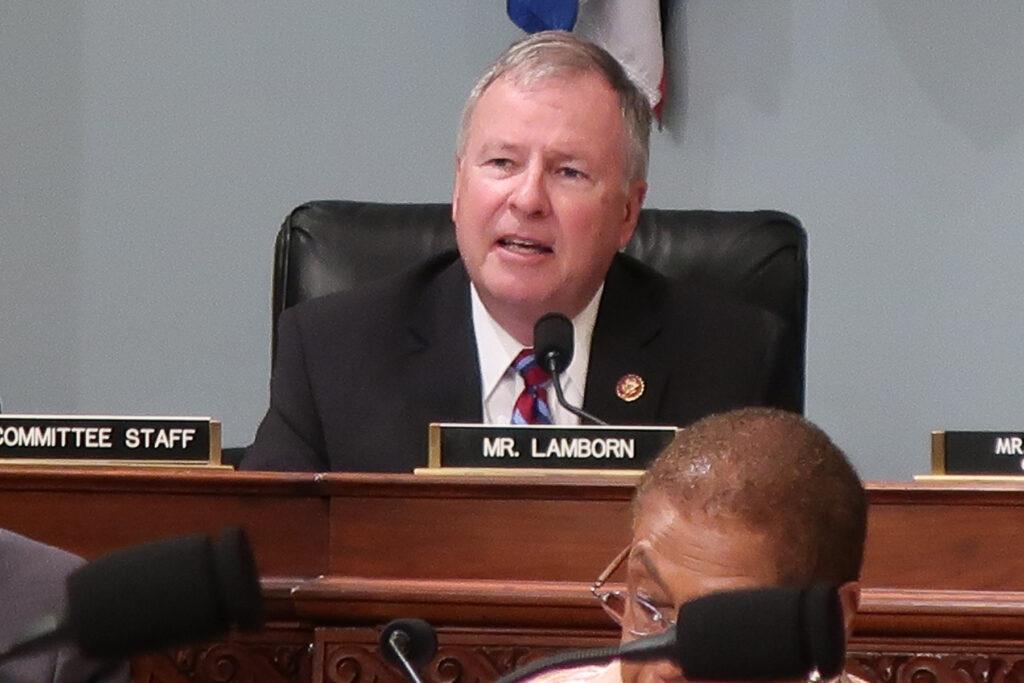

U.S. Rep. Doug Lamborn, a Colorado Republican, took his wife Jeanne Lamborn on nearly every privately funded trip he took between 2012 and 2023. Sponsors ranging from The Heritage Foundation to The Aspen Institute to The German Marshall Fund of the United States underwrote almost $90,000 in costs for Jeanne Lamborn for 15 separate trips she took with her husband. The couple traveled the globe, staying in posh hotels and resorts in London, Vancouver, Jerusalem, Berlin, Prague, Nairobi, Buenos Aires and Reykjavik, as well as locales in the U.S., the records show.

A spokesperson for Lamborn did not respond to two emails and a call to his Washington office seeking comment.

In February 2020, a private car took Lee and her new husband, the Rev. Dr. Clyde Oden Jr., from the airport to luxe German resort Schloss Elmau, a historic icon nestled in the Bavarian Alps. With Lee attending a five-day forum on U.S.-German relations, Oden could enjoy the amenities of a hotel listed by Condé Nast as one of the best in the world. Oden’s trip tab: over $12,000, records show.

Illinois Democrat Jan Schakowsky brought her lobbyist husband, Robert Creamer, on 22 trips, staying in luxury hotels in London, Prague, Istanbul and São Paulo, among other destinations. Private sponsors, most frequently Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit The Aspen Institute, paid nearly $135,000 for Creamer’s travel since 2012, records show.

Schakowsky described the “educational” trips as “no walk in the park.”

”We are often working 12-hour days speaking at roundtable discussions, meeting with dignitaries and scholars and examining local policies,” she said in a statement.

An array of private organizations has underwritten nearly $136,000 for California Democrat Ami Bera to bring his wife to Copenhagen, Tokyo, Switzerland, Iceland and the opulent Cloister resort on private Sea Island, Georgia, among other places, trip records show.

Bera did not respond to multiple calls or emails to his office seeking comment.

Of the 21 privately funded trips former GOP Rep. Fred Upton of Michigan took over the past decade, he brought his wife Amey Upton on all but one. Upton retired from Congress in 2023. His most frequent sponsors were The Aspen Institute or The Ripon Society, the records show. Amey Upton’s travel cost private sponsors over $113,000. She and her husband stayed in world-class hotels and resorts in London, Paris, Copenhagen, Geneva, Rome and Istanbul, among other global cities. The sponsors also paid for the Uptons’ to travel numerous times to Sea Island, Georgia, where they stayed in the luxurious waterfront five-star resort, The Cloister, set on a private island, the records show.

Messages left on cellphones listed for the Uptons seeking comment were not returned.

In dozens of instances, the cost of one relative exceeds $10,000 or more per trip, funding that critics claim lawmakers should report as taxable income. House rules lack any guidance requiring the disclosure to the IRS of family travel costs as income, a glaring ethical omission, according to critics.

Congress updated the U.S. tax code in 1993, mandating money provided to an individual for a spouse or dependent travel costs on a business trip must be reported as income unless the relative is an employee or had a legitimate business reason to be on the trip. An IRS spokesperson did not respond to calls, emails or text messages requesting comment.

It’s not only House members who can bring family on trips. Their staff can as well.

Since 2012, some of the most frequent staff travelers on both sides of the aisle have taken their spouses on dozens of trips to resorts and spas, courtesy of private sponsors such as the Congressional Institute. According to travel disclosure forms filed by staff members, the nonprofit — which takes pride in its “premium level” programming, provides “valuable educational and organizational tools” for managing a congressional office. It also provides the spouses of these staffers the chance to stay at world-class resorts such as The Greenbrier in West Virginia. While congressional staffers are attending lectures, spouses can try their hand at falconry or yoga classes, enjoy spa treatments or play golf.

An analysis of dozens of staffers who traveled most frequently in the last decade shows private sponsors spent more than $12,000 so spouses could accompany staffers on these educational trips.

While staffers tend to keep their privately sponsored travel domestic, their bosses can be found traveling around the globe. The most frequent international destinations for House members and relatives are Israel, luxury resorts in Kenya and other regions of Africa, and Germany. U.S. popular travel spots include Virginia’s horse country, San Diego and Santa Monica, California, and annual jaunts hosted by the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation to historic Tunica, Mississippi, home to casinos, golf courses and rich Southern hospitality, records show.

Boston University and the Howard Center did not examine travel records for the much smaller Senate, which reported more than 2,600 trips during the same period. The Senate disclosure forms do not provide sponsors or destinations in a format that can be readily analyzed.

In addition to travel disclosures, nonprofit tax records and lobbying registrations, the examination by the Howard Center and Boston University also used data collected by OpenSecrets, a nonpartisan government watchdog organization, and by LegiStorm, a public affairs information platform.

In nearly 90 trips in which relatives traveled, legislators added extra days to their travel. While members are required under House rules to cover some of those costs personally, it is still a bargain for lawmakers, as private funders almost always cover round-trip airfare to the trips’ original destination for members and relatives, trip records show.

Colorado Democrat Diana DeGette leads frequent-flier House members in adding time to official trips, sometimes by up to five additional days. On seven of the trips, one family member joined her — either her husband, Lino S. Lipinsky de Orlov, a Colorado judge, or two different children, with stops in Belgium, Prague, Istanbul, Japan and a beachfront Ritz Carlton Hotel in Florida, trip records show.

Numerous travel invitations include a lawmaker’s spouse by name, another ethical red flag, critics said.

“Dear Diana: I would like to invite you and Lino to participate in a congressional conference on U.S. Russia Relations: Policy Challenges in a New Era,” reads one invitation to DeGette, from the nonprofit organization The Aspen Institute Inc. Congressional Program, a top funder of House trips since 2012. The Jan. 25, 2017, letter adds: “Expenses for you and Lino, including business class airfare” will be covered.

Such direct solicitations to members of Congress impart a basic “lack of ethical hygiene,” said Dylan Hedtler-Gaudette, senior government affairs manager for the Project on Government Oversight.

DeGette did not respond to requests for comment.

In response to questions about whether it was appropriate to include a lawmaker’s spouse on a trip invitation, a spokesperson for The Aspen Institute said in an email: “Congressional Ethics rules are clear that members may be accompanied by a spouse. As the invitation in the document you attached indicates, we take compliance seriously and our programming is aligned with the spirit and the letter of those rules.

“For more than four decades, the Congressional Program has encouraged constructive interaction between members, and we have found that the presence of spouses certainly contributes to better relationships among them. Our programming is funded by foundations and 501c, free of special interests and lobbying. We’re proud of the role the Congressional Program has played in strengthening bipartisan cooperation and providing a space for members to delve into complex and pressing public policy issues.”

It is unclear if any House members report the family travel costs as income.

When asked about this and other travel guidelines for members and staffers, Tom Rust, the chief counsel and staff director for the House Ethics Committee, declined to comment.

The IRS ignored a 2006 complaint Holman filed requesting a probe into whether lawmakers broke federal law by failing to report relatives’ costs as income. He said it has never occurred.

Maggie Mulvihill, Shannon Dooling, Irene Anastasiadis, Safiya Chagani, Suryatapa Chakraborty, Sicheng Che, Clara Cho, Ella Corrao, Julia Deal, Mingkun Gao, Daniel Gibbons, Gioia Guarino, Faith Imafidon, Andrea Macho, Eliana Marcu, Maya Mitchell, Deidre Montague, Mackenzie Li, Zichang Liu, Caitlin Reidy, Amber Tai, Laura Tickey, Ella Willis, Xinyi Yang and Ziyue Zhu of Boston University also contributed to this story. Mulvihill and Dooling are associate professors of the practice of journalism.

The Howard Center at the University of Maryland is funded by a grant from the Scripps Howard Foundation in honor of newspaper pioneer Roy W. Howard.