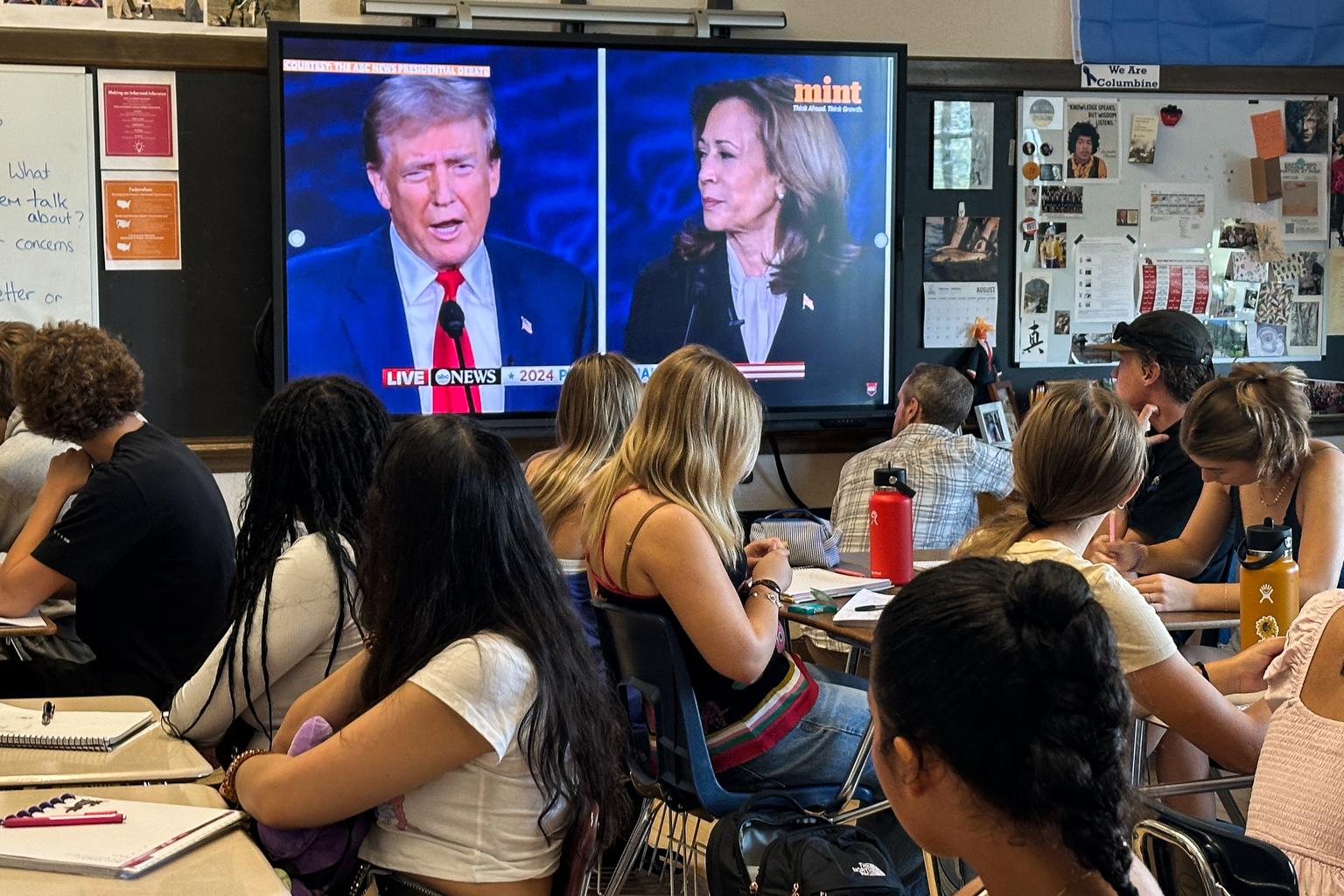

Matthew Fulford’s Denver East High civics class listens with rapt attention.

“They have destroyed our country with policy that’s insane,” says former President Donald Trump, in a 10-minute presidential debate highlight reel projected on the classroom whiteboard.

Many of the students watched the full debate the previous night.

“Well, as I said, you’re going to hear a bunch of lies and that’s not actually a surprising fact,” responds Vice President Kamala Harris.

Fulford couldn’t imagine teaching civics during a presidential election and not helping students make sense of it.

That’s not the case for every teacher. A recent nationally representative survey found most educators didn’t plan on lessons addressing the 2024 presidential election. Some were concerned about parent complaints. One in five said they didn’t believe their students could discuss the topic with one another in a respectful manner.

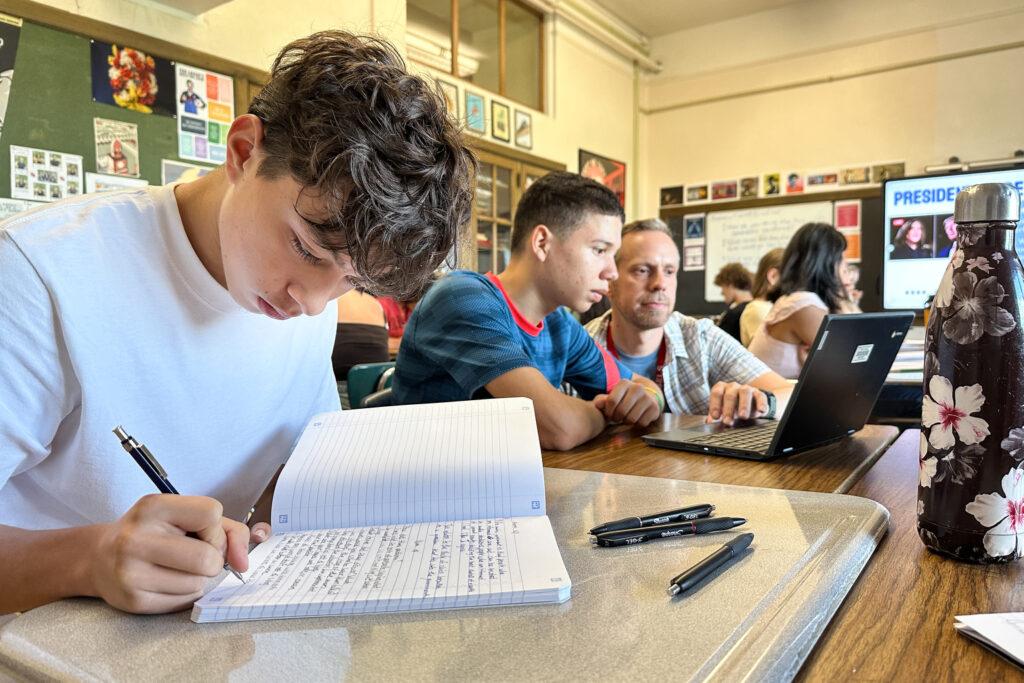

“Civics is about helping students prepare to be informed and active members of society, so by not teaching the election, I'd be undermining my own goals,” he said. “I am careful to create an environment where all students feel comfortable expressing their views, and I want us to model civil discourse. Even if students aren't seeing civil discourse from many of our elected representatives I want them to experience it in the classroom.”

The class is studying freedom of expression and how “We the People” can check the power of the government. Fulford emphasizes the importance of voting, being well-informed, and speaking up for your values and beliefs. The students take notes on the debate and the candidates' closing statements.

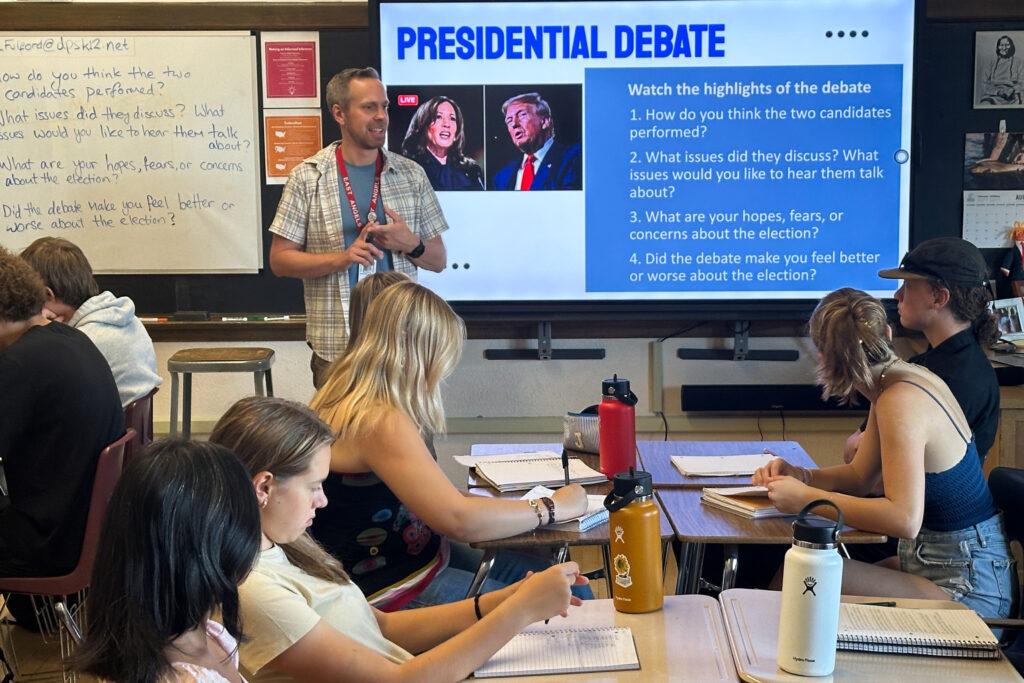

Fulford directs his students to talk in groups, addressing four questions:

- How do you think the two candidates performed?

- What issues did they discuss and what issues would you like to hear them talk about?

- What are your hopes, fears or concerns about the election?

- Did the debate make you feel better or worse about the election?

A student, E, wanted Trump to lay out a clear vision for the future but said he didn’t.

“Instead of talking about what he would do he was just talking like, Kamala hasn’t done this, she said she was going to do this but she hasn’t, instead of talking about what he would do,” E said.

But other students noticed both sides didn’t try to discuss the points made by their opponents. Trey, 18, said Trump didn’t respond to Harris’ points about abortion, “but then when Trump would bring up some of the issues that came up in the Biden administration with immigration, she kind of dodged them.”

One student liked Harris’ proposal to provide $25,000 in down payment assistance for first-time homebuyers.

“The housing crisis is crazy and it’s really hard for young people to get on their feet,” she said. Another student said there was too much focus on foreign wars and not enough details about domestic policy.

A couple of students said the debate was funny, as in — a joke. Another student disagreed.

“I can’t laugh at this and find it funny, because it is who will be making the change that everyday people have to deal with every single day,” said Zoe.

But overwhelmingly, the students were surprised and dismayed that the candidates dodged so many questions. They were exasperated that the two talked over each other and spent valuable time attacking one another instead of discussing each other’s platforms. High school students are used to following the rules of debate and discussion. Cora found what she saw terrifying.

“They were both behaving like children, like going on tangents and fighting and engaging with each other. Meanwhile, I feel really unsafe, and I want to hear about the policies that they want to enact and like, actually what's going to happen instead of arguing with each other and they didn't do that.”

Teenagers ‘desperately want opportunities to try out their ideas’

Fulford, with 15 years’ experience teaching social studies, is comfortable discussing potentially controversial topics in ways that don’t alienate his students. He said he would have found this election very difficult to navigate as a new teacher.

But he points to the American Historical Association’s recent comprehensive report finding that history teachers overwhelmingly are dedicated to “presenting multiple sides to every story” and helping students find their own voice.

“Teenagers have nuanced opinions on a variety of issues and they desperately want opportunities to try out their ideas and to listen to others,” he said.

He asks the students why they think Harris attacked back when they didn’t expect her to. One student said it is a natural instinct to fight back when you are being attacked, but that she wanted to see Harris rise above that. Ali, 18, has another viewpoint.

“I do feel like at this point in the election, it's what she needs to do because right now, she's just trying to win the swing states. She’s clear on her policies, people know what she wants. So, she's trying to get people to change their opinion on Trump.”

Ali is anxious about the election. She’s voting for the first time and is in a club to register 100 percent of high school seniors. She’s studied the candidate’s platforms carefully.

“I feel like that's what makes it so much more important to me because I'm invested in all of our futures,” she said. “I want to know exactly what to expect.”

Can students trust that adults have their best interests in mind?

Ali and several other female classmates said they’re worried people won’t vote for Harris because she’s a woman. A few signs of the reported ideological gender divide in Generation Z — with young women increasingly more liberal than some young men — popped up.

A couple of male students, one who holds some Republican views but is voting for Harris and the other who is undecided, expressed a sense of alienation that they see Trump tapping into. But many students regardless of race, ethnicity or gender felt the candidates weren’t really speaking to young people.

“Being African American, racial issues and police brutality and stuff like that, I feel like 100 percent should have been talked about way more and just wasn't, like, at all,” said Helen, 17.

Others found it surprising that gun control wasn’t mentioned or the fentanyl crisis or college affordability, issues that hit close to home for young people. Some were disappointed that climate change, the greatest threat facing the planet, was discussed (and only by Harris) for less than a minute. There is a sense these students want to feel as though they can trust the adults to have their best interests in mind. The debate shook that trust a little.

National polls show about 42 percent of young people don’t believe their vote will make a difference, and 56 percent believe politics today are no longer able to meet the challenges the country is facing.

Fulford puts the fiery political times into context

“This is kind of a new thing,” Fulford tells his students. “The past 10 years the debates have gotten pretty fiery. When I was your age, there wasn’t name-calling, there wasn’t shouting. It wasn’t like this.”

A week later Fulford shows his students a clip from one of the 1960 Nixon-Kennedy debates. The students are struck by how much detailed policy was discussed, that the candidates didn’t seem to hate each other. It’s a style of politics these students have never seen in their lifetimes.

Students said the 1960 debate was pretty boring — but they’d much prefer politics to be boring. A strong majority of these students are afraid of violence after Election Day, Nov. 5, no matter who wins.

“The idea of Trump losing almost makes me more worried. Not because I want him to win,” said Eli. “But after the backlash that happened with the whole January 6th riot, which he incited when he lost last time, I'm worried about what could happen if he loses again, if we see that again if we see something worse.”

Fulford tells them it’s important for people to hear what youth are thinking, their hopes and fears.

“Your opinion matters, your voice matters,” he said. “People want to know what you think about this. You are the future.”

Trey reminds his classmates who will be voting that there are dozens of important issues, state and local, on the ballot where they can have a big influence. He dislikes that the presidential race hogs all the attention.

“There’s a lot of things that are really important to be educated on and to vote about.”

This year, 73,523 Coloradans turning 18. While there have been significant increases in some states in registering young voters since July, Colorado is down 1 percent as of the beginning of September compared to the number of youth registered on Election Day in 2020. Colorado is one of the states where youth can pre-register to vote online or by paper at age 16, according to the Civics Center.

Youth typically turn out to vote at significantly lower rates than older Americans.

Not Nathaniel. He’ll make his opinion known. He turns 18 on Nov. 3, two days before the election.

“I’m looking forward to voting for the first time. I think it’s a very important election, and it’s high stakes so I’m especially excited.”