Lorenzo Calloway, 13, is soft-spoken and polite especially with strangers.

His mom was in the military, so it’s “yes, ma’am” and “no, ma’am.”

But there’s also a wariness in him. Haltingly Lorenzo tells the story about the first incident in a series of racist incidents targeting him over the course of two years at Windsor Middle School, less than a half an hour northwest of Greeley in Weld County.

Lorenzo was a new sixth-grader at the school in 2022. The family had just moved to Windsor. Lorenzo was excited to go to school. His mom said he’d be the first one up, clothes laid out, ready and raring to go. The active 11-year-old loved football, and the new school had a team.

One day in September, his math teacher was asking kids about their pets. Lorenzo said he had a lot of animals.

“I bet when you look in the mirror you see a monkey,” Lorenzo recounts the teacher saying to him.

Lorenzo is Black.

“Everybody started laughing,” said Lorenzo, softly.

After multiple racist incidents that took place well into the 2023-24 school year, his mom, Shelly Calloway, filed a civil rights complaint desperate to bring change and a desire to show that Lorenzo’s civil rights were violated. They’re still waiting.

The damage caused by racism in schools is severe

A new CDC report shows one in three teens report experiencing racism in school. There are severe consequences for a child’s life when schools and districts don’t act swiftly to eradicate bullying and racist conduct. The study showed poor mental health, suicide risk and substance use were higher in students who reported experiencing racism in school.

Meta-analyses of bullying show it damages a number of brain regions in children. Racial discrimination can also lead to anxiety and depression.

Lorenzo’s story reflects the lengths some families must go to get schools to follow federal and state laws aimed at protecting children from racism and discrimination. One problem is the burden is on students and families to know what qualifies as discrimination and harassment and what to do when it happens while risking retaliation. And it relies on parents trusting schools to take immediate action.

“I'm sending my kids to school and I'm trusting that their principal, their assistant principal, their teachers are all going to rally around every child and make sure that they're safe,” said Calloway.

Repeated trips to office to report racism

Lorenzo’s mom Shelly Calloway encouraged her children to report to the school when they heard racist comments that made them feel uncomfortable. She trusted administrators to respond to them internally.

But when the teacher made the monkey comment to her son, Calloway went to the school the next day and talked to the educator in the hall. Calloway said the teacher apologized to her and said that he shouldn’t have said that.

“And I was like, well, I appreciate the apology but even as an adult …. what would make you think of all things to say that to my son? … Where did that even come from? He's like, ‘I was joking and I even told him before he left, you know, hey, thanks for being the butt of my jokes today, you made the day. But it was just in playing.”

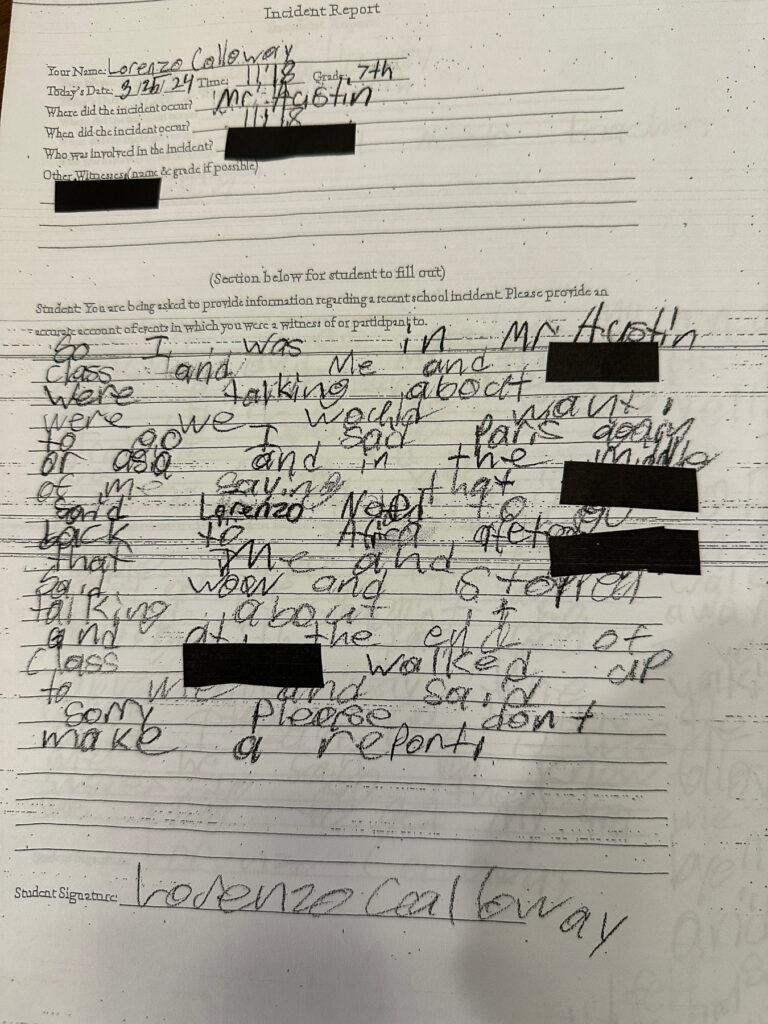

But when that class period ended, Lorenzo said the teacher asked him not to report the incident and that he was sorry and didn’t mean it.

Lorenzo made the first of what would be many trips to the office to report a racist or bullying incident.

A year and a half later Weld RE-4, which is less than 1 percent Black, responded to Lorenzo’s incident complaint about it, and seven months after Calloway filed a complaint on a different form. The district said the allegation was substantiated — in part. It concluded the remark, given the context, wasn’t made with discriminatory intent. But it said the teacher’s words would “likely and did cause” Lorenzo discomfort. It said due to confidentiality policy, it couldn’t share what specific actions it took with respect to the employee. He still teaches at the school.

“As a district we are currently working on adding additional training for employees on discrimination prevention and will reinforce best practices whenever possible in student and staff conversations,” it said in the letter written in May this year.

The district declined interviews.

In a statement it said it works to create a safe and secure learning environment for all students that is free from threat, harassment, or bullying.

“We look to ensure our schools are places where all students are accepted and feel a sense of belonging; a safe space to come to and learn from. Bullying of any form is not tolerated.”

It wasn’t just Lorenzo who was a target

That same semester in 2022 another parent detailed in front of the Weld RE-4 school board the racism, bullying, intimidation and “hateful words and actions” her biracial children had experienced since elementary school. That included racial slurs and a “horrifying” incident at the middle school where some students dressed up as monkeys for Halloween.

She begged the board for action. She recommended specific trainings in restorative practices and professors at Colorado State University who could help with diversity, equity and inclusion training and education.

Officials later told her they take bullying and harassment seriously. The district had implemented a “Character Counts” curriculum, counselors paid quarterly visits to support student needs and to let them know how to report bullying.

But nothing really changed.

A year after that meeting, as Lorenzo walked the school’s hallways, he’s called the n-word and other racist slurs. Students would switch lights off in class to make it dark and say, “where’s Lorenzo?” There were cruel Snapchats to Lorenzo, like the one that said “no one else wants you there. Not even the teachers.”

It got hard to focus in school.

“It was all the time,” said Lorenzo.

Reports culminate with federal civil right complaint

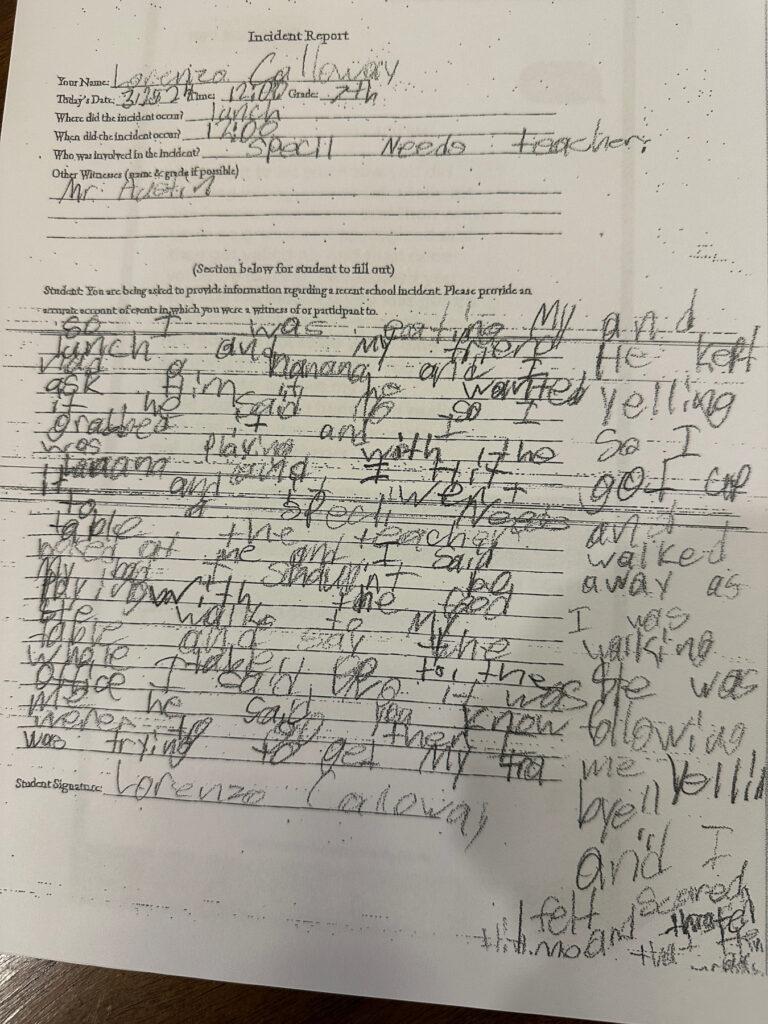

Page after page of complaints are laid out on the Calloway’s dining room table. They’re painstakingly documented in the sixth grader’s handwriting. Calloway pressed for accountability. Last October, she filed a federal civil rights complaint.

Calloway said the principal told her they were trying to navigate the situation but they didn’t know exactly what to do.

“If you don't know how to navigate it, then do you not know how to reach out to someone that can possibly come in to help? But at no point or turn with any incident were they ever wanting to see how is it affecting Lorenzo? How’s it affecting our day-to-day life?”

‘I just didn’t want to learn’

It was affecting it a lot.

Lorenzo’s sister, Auz’sia, left the school in the first semester of 2022, declaring “I can’t do it.” She finished out seventh grade living with a friend of the Calloway’s in Denver.

Calloway said trying, without success, to get something done about Lorenzo’s torment, exacerbated her own PTSD from her time in the military. And Lorenzo often didn’t want to go to school. He’d tell his mom that his head or stomach hurt. It affected his whole outlook on school.

“I just didn’t want to learn,” he said. He liked football though and thought he could push through.

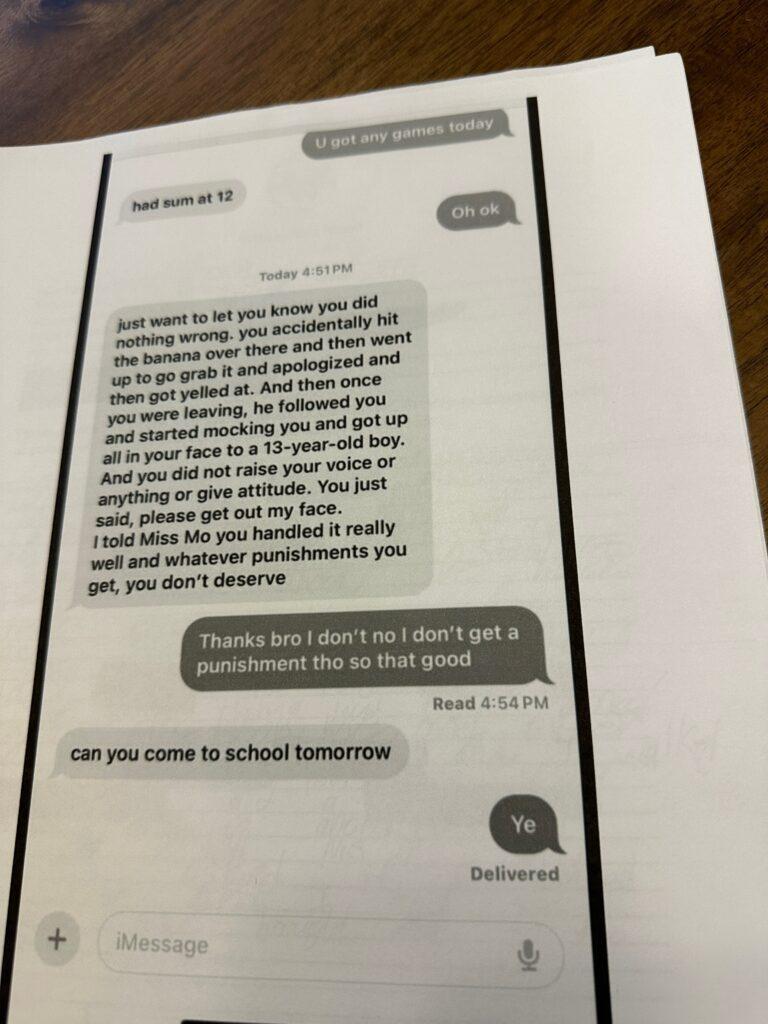

One day in the cafeteria, when a banana being tossed landed on the floor, another teacher accosted Lorenzo.

“He was yelling at me and he's telling me, ‘get out, get out, get out!’ And as I'm trying to walk around him, he was walking towards me and like trying to block me from walking out.”

Lorenzo wrote in his complaint that it was scary. He was taken to the office where he stayed nearly all day. The school called Calloway and she asked why her son was still there when a video camera showed he didn’t throw the banana.

“He’s missing education time…and he has text messages from people that were in the cafeteria that (state), ‘Why was he running up on you being aggressive with you, yelling and spitting in your face? And I'm like, what are we going to do about that?”

The school said HR would handle it.

Lorenzo’s demeanor at home changed. Anger. Depression. He isolated in his room. When the family finally got him to join the dinner table one night, he said to his brother “whatever monkey.”

“Everybody at the table kind of froze,” said Calloway. She knew it was serious, affecting Lorenzo’s self-image and esteem. She got him into therapy.

At one point, a district official told Calloway that officials had a lunch meeting with students who were racially taunting Lorenzo to educate them about what they were doing. That was on a Wednesday.

On Friday, “Lorenzo was told that “How the Grinch Stole Christmas” should have been changed to Black people breaking out of the zoo and stealing stuff like they do,” said Calloway.

Frustration all around

A school official told Calloway he was frustrated with the situation.

“You're frustrated because you're having to deal with it. I'm frustrated because my child is actually enduring it,” she told him.

Schools are supposed to do timely investigations, discipline offenders, and offer emotional support to targeted students. A violation of federal civil rights law happens when schools are “deliberately indifferent” to persistent racial harassment. The district said all appropriate practices and procedures were followed, including disciplinary action if warranted. Not according to Calloway.

“His principal and even the superintendent, they failed him,” she said.

In June this year, the district said it would pay for tutoring for Lorenzo for missed school. It outlined steps to confront future discrimination and harassment. It said Lorenzo can do eighth grade on a safety plan at Windsor Middle School or the district will pay to transport him to another middle school in another town.

Calloway didn’t respond. She already made up her mind. For Lorenzo’s safety, they emptied the bank account and moved away from Windsor.

“That should have been home.”

Carrying trauma to a new school

Now, Lorenzo smiles and laughs as he plays a video game at his new apartment. He has been diagnosed with PTSD from bias-motivated harassment that meets Colorado’s hate crime criteria and depression. The racial trauma has affected his ability to function in school.

“I just feel like somebody is going to say something out of nowhere,” he said.

Calloway said her son is a shell of himself. He doesn’t leave his room; he barely wants to eat; he no longer plays football. School is a struggle. He can’t stay focused.

“It's taking a toll on each one of us differently and I'm even trying to just keep myself grounded because he needs me.”

The therapist Lorenzo sees reports that the school’s failure to intervene or protect him and a lack of timely or meaningful response were separate acts of revictimization.

Lorenzo said it helps to talk to the therapist. It’s good too, he says, to be around more students who look like him. He feels like he won’t get bullied.

“It makes me feel better around people of my skin color.”

New student safety coordinator hired

In a statement, Weld RE-4 said administrators got training this summer on investigating, analyzing, and reporting discrimination and harassment. The district improved all-staff bullying and harassment training. It hired a new student safety coordinator. Windsor Middle School started a mentor and anti-bullying program, called WEB, an acronym for “We All Belong.” It plans to have a speaker on the topic of anti-bullying and racism.

“Even if one student has a poor experience in any of our schools, it is one student too many,” the district said in a statement. “We take reports of bullying or harassment very seriously. We continuously work to learn and grow each to ensure our schools are safe and all students feel a sense of acceptance and belonging. Bullying of any form is not tolerated in Weld RE-4 Schools.”

“But who's holding them accountable?” asks Calloway.

Meanwhile, Calloway’s federal civil rights complaint is still being investigated. The district has asked for a resolution agreement to make corrective actions. It’s unclear whether there’ll be a finding on whether Lorenzo’s civil rights were violated. That’s what Calloway wanted.

At home, Calloway makes dinner with Lorenzo, savoring the happy moments. They joke about sneezing as they add in the seasoning. But she says the whole family has suffered.

“It hurts,” she said. “But for me and for my kids, we're not going to allow that to determine who we are. But we can call them out on the type of people that they are and it shows that they didn't stand for what's just humane. And for that, I will never forgive them.”