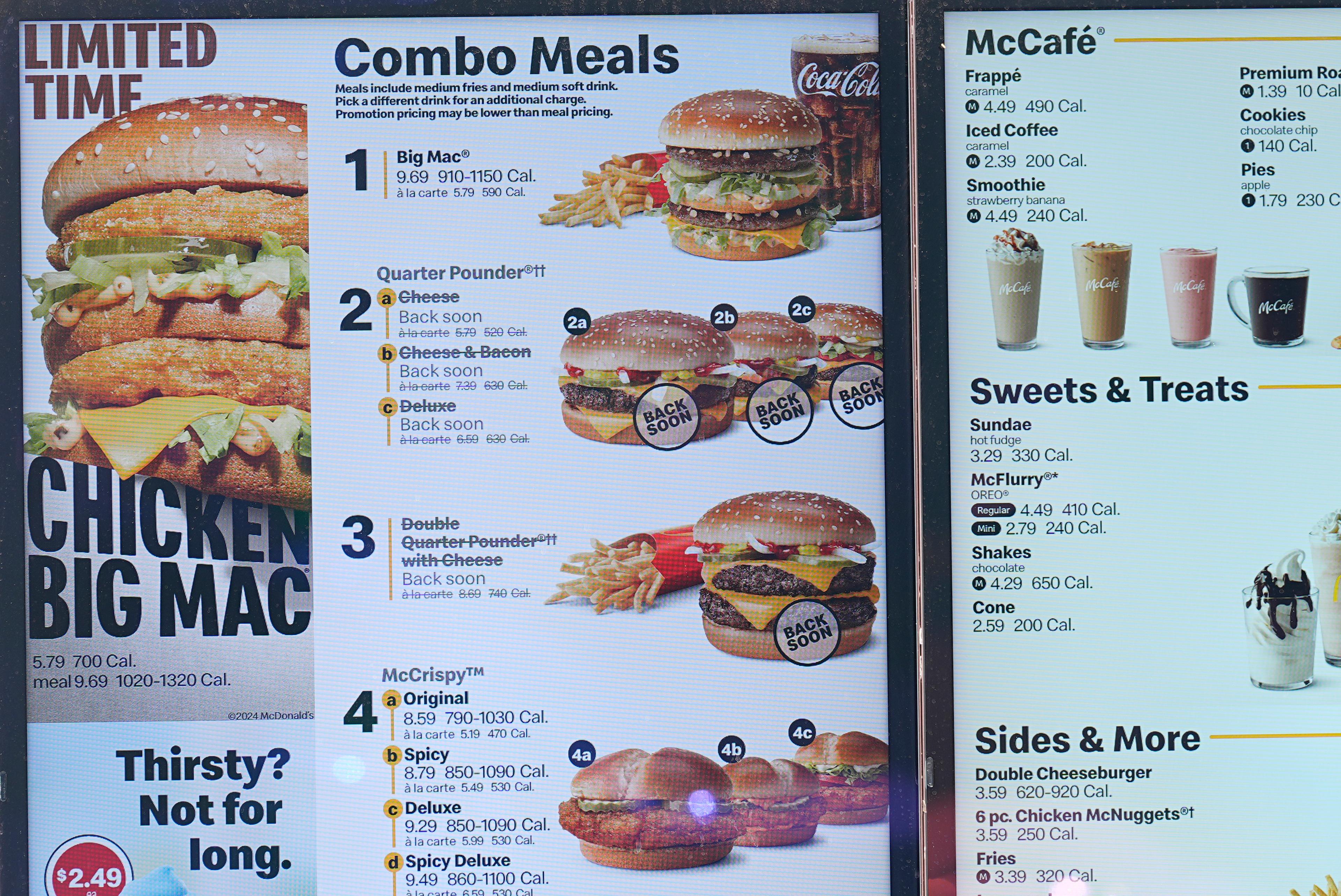

Quarter Pounders are headed back to McDonald’s restaurants in Colorado after an E. coli outbreak, but a food safety expert said investigators are only beginning their work.

The Colorado Department of Agriculture reported Sunday that it found no traces of E. coli in samples of fresh and frozen McDonald’s meat patties. That makes raw onions served on the burgers the apparent source of the contamination that sickened at least 75 people in 13 states between Sept. 27. 2024, and Oct. 10, 2024. About a third of those cases were in Colorado, where one person died.

The onions were recalled last week. McDonald’s has said they came from a Taylor Foods facility in Colorado Springs.

Alice White is a senior instructor at the Colorado School of Public Health and leads a team at the school’s Integrated Food Safety Center of Excellence. She told Colorado Matters host Ryan Warner investigators will try to trace the onions’ path from the fields to the restaurants.

“At the moment, (the U.S. Food and Drug Administration) is putting a lot of work into figuring out what happened and figuring out where in the production chain the product got contaminated and what went wrong there,” White said.

Improved regulation and food handling practices have made meat contamination less common and the focus now is shifting to produce. While each outbreak is different, experts are getting a better grasp on the problem, she said.

“We're learning more about how produce becomes contaminated, and that's an important step in order to be making these changes with policies or practices that can improve the food safety or produce.”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Ryan Warner: Why is produce a particular problem when it comes to E. coli?

Alice White: A few decades ago we really thought of ground beef as the main source of E. coli infections, and that's changed a lot over time. Part of that reason is because the food industry has made a lot of improvements around food safety with meat and ground beef in particular.

There are a few reasons why produce has increasingly become an issue. One is there have been changing consumer food practices, so people are eating more produce, which of course is a great thing. Produce is often uncooked or undercooked, which can make it a little bit riskier if it's contaminated than a meat product that's contaminated. Also, produce is often commercially distributed, so that means a single farm or a single growing region can be producing the product and then distributing it to many different locations in other states across the country. So if there's an issue, then that product is being sent out quite widely, so that can mean a lot of people are potentially exposed.

Warner: So just a whole host of trends there contributing to this picture. You say that there have been vast improvements in how we manage hamburger meat. Could those same innovations be applied to produce then? I mean, if we've made progress there, can we make progress elsewhere?

White: That's definitely the goal and regulatory agencies, the food industry and Public Health are all working in that direction. We're learning more about how produce becomes contaminated, and that's an important step in order to be making these changes with policies or practices that can improve the food safety or produce.

Warner: What are the holes in our knowledge about produce?

White: So every time an outbreak happens the public health and the regulatory agencies do a lot to investigate what happened, and every outbreak can be a little bit different. So at the moment, FDA is putting a lot of work into figuring out what happened and figuring out where in the production chain the product got contaminated and what went wrong there. So we're always learning more about how our food can get contaminated and what we need to do to make it safer.

Warner: McDonald's has linked the tainted onions to a Taylor Farms facility in Colorado. Springs. Indeed, there is an investigation underway. Taylor Farms has said it voluntarily recalled the onions, and its other products are safe.

The Associated Press reports that this bacteria, E. coli, causes about 74,000 infections in the U.S. every year leading to more than 2,000 hospitalizations, 61 deaths. If we are eating more produce, much of it uncooked as you say, and as you've described how this is distributed commercially all over the country, do we have to accept some level of E. coli in the food supply?

White: I think public health regulatory agencies and the food industry are all working very hard to prevent these outbreaks, and none of these groups want there to be any risk to the public. And of course, the vast majority of our food does not have that risk because we have a very robust safe food system in the United States. And when something like this happens, we learn a lot from it, and we try to make as many changes as we can to make sure that it doesn't happen again.

Warner: What is within my power as a consumer, either of fresh produce at the grocery store? Or I'm thinking of my dad who is obsessed with onions. Every time we go out, he orders an extra plate of onions to put on the burger and then snack on on the side. What would he do?

White: In terms of general food safety practices, of course, always hand washing, following food safety steps at home – so cleaning your hands, cleaning utensils, cleaning surfaces and doing that often. Separating food – food that needs to be cooked in order to eat and food that is going to be consumed ready to eat, those you want to keep separate. And cooking to temperature, refrigerating perishable food. So those are all general food safety guidelines that we can follow at home. And then in a situation like this, of course, following the guidance relating to the specific recall on FDA's website. Some of the other things that can help are people with diarrheal symptoms should stay home from child care as well as if they're working in a job that involves handling food

Warner: Because it can spread that way.

White: It can. This is not the most common way we see E. coli spread, but it does happen. We call this secondary transmission.

Warner: Are you the type who looks up health records for a restaurant?

White: I do. When it's readily accessible I definitely take a look at that. And so I think it's important that it's readily accessible for people to have that information.

Warner: Have you steered clear, then, of a restaurant whose review is not sterling or...

White: I think it's something that I factor in when considering where to eat. But also restaurants or businesses that experience something like this, which of course none of them want to, they often are quite ready to make changes to their practices and ensure that what they're serving to the customers going forward is safe.

Warner: Alice, I'm really fascinated by the timeline in this story. So the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says the first known case in this E. coli outbreak was in September, and the last sickness they know of was October 10. Why did we not hear about this, and why wasn't the recall done until the middle of last week?

White: It takes time to figure out what is going on in a situation like this. So I'll just walk through what happens: When people become ill, they decide to go to their physician, and not everybody does that. And maybe it takes them a couple of days to make that decision. Usually it has to be a fairly severe illness for us to decide to go to the doctor for diarrheal illness. Then of course they have to agree to provide a clinical sample, and then that goes to testing to the clinical lab. And then the clinical lab, if it's positive for an infection for a pathogen like E. coli, they forward it on to the state public health lab where the state public health lab does additional testing to determine the subtype and do some sequencing to look at the genetic characteristics of the pathogen.

And then we need to connect the dots. So Public Health starts connecting the dots, looking at that laboratory data to see how the pathogens, the infection that people have, is related to each other so that we know that there is indeed an outbreak. That whole process takes some time.

As soon as Public Health knows that somebody has E. coli, which is reportable in Colorado and other states, then they call that person on the phone to learn more about their illness. That's even before we have the sequencing information that tells us about whether or not we have an outbreak, whether or not multiple people have the same infection. That's usually local and state Public Health, doing that work very quickly. As soon as they learn that somebody has an infection, they call them and they ask questions about their illness, about their symptoms, about what they have been exposed to. So there's a lot of work happening at local and state health departments before we even know that it's an outbreak.

And then once that information starts coming in that it's an outbreak Public Health starts connecting the dots and figuring out what exposures people might've had in common. So that all takes some time, as it does even when Public Health knows it's an outbreak and they're starting to take action, the regulatory agencies start to take action, it's still going to take some time for additional cases to come through and to be tested and for Public Health to be notified about them.

Warner: I think the key to what you're saying there is that much of this is about people reporting what they've experienced, and so that makes me think that there's likely more folks who were affected by this outbreak who simply didn't go to a doctor or report to Public Health.

White: Absolutely. There most certainly are, in general, people who have these infections but it might not be severe enough for them to go to the doctor, even in an outbreak situation where people are aware of it. So it is of course important that if people think they have been exposed and they have symptoms to get in touch with their healthcare provider. And then also if Public Health calls, to pick up and talk to the public health investigator so they can share additional information. That information is invaluable in an investigation.

- McDonald’s Quarter Pounder back on menus after testing points to Colorado Springs facility as E. coli source

- Coloradan who died from E. coli infection linked to McDonald’s food was Mesa County resident

- One dead, 26 sick in Colorado amid ‘severe E. coli outbreak’ linked to McDonald’s food

- Grand Junction teen fights kidney failure after eating McDonald’s Quarter Pounders