Going to jail shouldn’t mean you lose your say in our democracy — that’s the thinking behind a new state law requiring all jails to offer an in-person opportunity for inmates to vote, making Colorado the only state in the nation to require its jails to offer in-person voting.

“This is my first time voting,” said 36-year-old Raul Vidaurri who is serving time in the Denver County Detention Center. He’s said he’s originally from Texas. “But I've been out here for 10 years trying to go back home and I just got into a bit of a situation, but I'm glad to be in here, get my head right.”

Vidaurri is one of the inmates taking advantage of the in-person voting law and said he’s excited to cast his ballot.

“Very new, I guess more like a new start, new beginning,” he said.

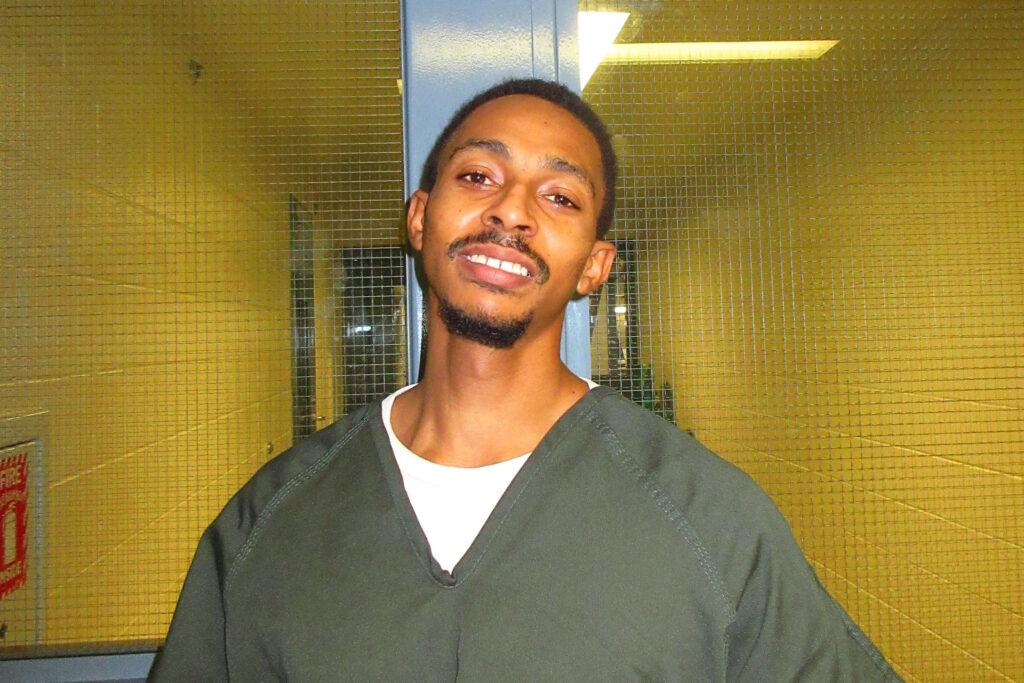

Fellow voter Jerome Whitfield said he’s been in jail for a few months, and his top issue is affordable housing.

“So I'm just happy I'm able to participate. I thought my background may prevent me from that, but thank God, by the grace of God and everything else, I'm able to, so makes me feel like I'm still involved in the community out there.”

Under Colorado law, the only people in the justice system who aren’t allowed to vote are those serving a felony sentence, but once they’re paroled, they get the right to vote back. Inmates serving time for a misdemeanor or awaiting trial never lose the right to vote. Democratic State Senator Julie Gonzales of Denver was the main sponsor of the new law. She said so much of criminal justice is focused on punishing people.

“But when we actually remind folks, ‘Hey, look, yes, you have caused harm and we are going to hold you to account for that, but also your voice still matters’ …. And (that) reminds them of their humanity.”

She notes that 90 percent of people in jail will eventually return to the community. And while it used to be common practice in the U.S. to make felons ineligible to vote, in some cases permanently, over the last few decades more states have been reinstating the right to vote for former felons, according to the National Council of State Legislatures.

Kyle Giddings helped advocate for the new law at the statehouse with his work at the Colorado Criminal Justice Reform Coalition. He spent time in the Jefferson County jail a decade ago while heavily addicted to opioids and said he saw firsthand how much this right matters to people.

“I was talking with a fellow who was talking about how he was no longer going to be able to vote because he had a felony conviction now on his record.”

But Giddings, who had previously worked in politics before his addiction, knew the laws in Colorado.

“And suddenly there (were) like 20 guys, we were all talking about voting, and I was talking to guys that were in their 30s, 40s, and 50s that had never voted before.”

His organization and others currently visit the Denver county jails a few times each month to help register eligible voters.

“We are constantly running into folks that just never knew they had the right to vote because of old felony convictions.”

Colorado’s election rules already allowed counties to do in-person jail voting, but only Denver had tried it before it became a requirement this year. Inmates can also get a ballot mailed to them in jail, but Amanda Gonzalez, the Jefferson County Clerk, said that just didn’t happen much. Her county ran the numbers and said voting from jail accounted for just around a half percent of voter turnout.

“(That’s) in a county where we usually have north of 70 percent voter turnout So (we were looking) at, ‘What are the ways that we can make this better?’ And I think the obvious answer was in-person voting.”

But the idea got pushback at the legislature from some of the sheriffs who run county jails. They worried about safety, logistics, and how to navigate the process. Under the law, county jails are required to offer six hours of in-person voting.

So far, counties say it’s going well.

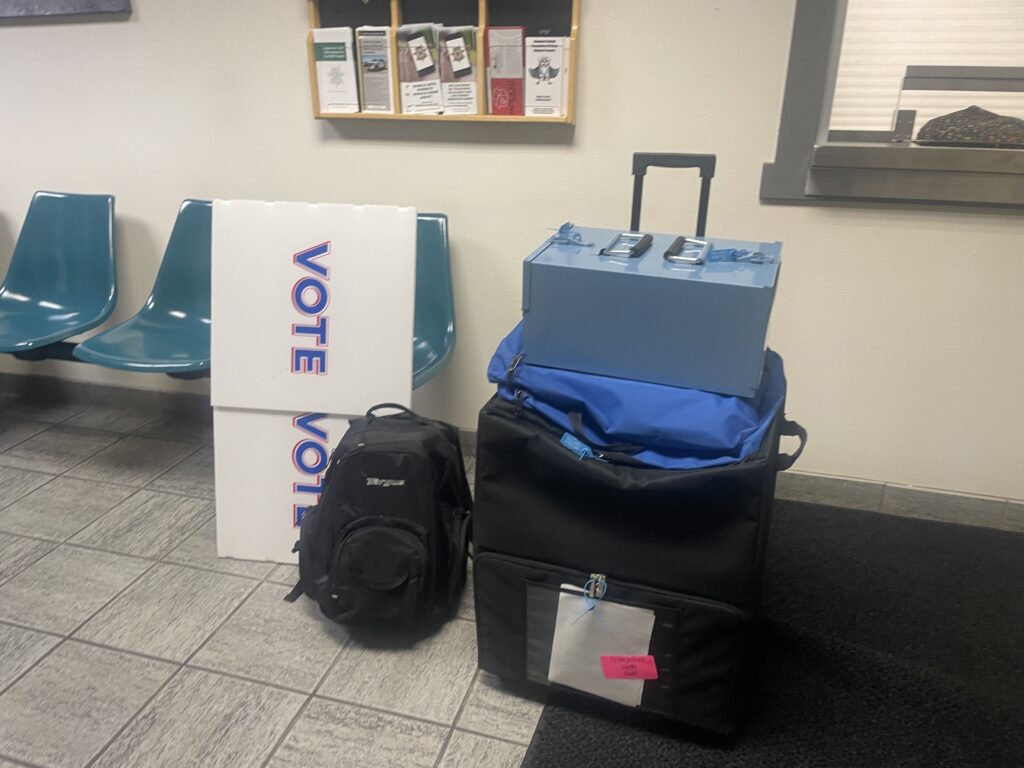

Recently, staff from the Garfield County clerk’s office brought their equipment to the jail through a secure entrance and set up for a day of voting. Inmates were allowed to vote in the women’s library, on a ballot marking device that would print out their answers, or take their ballots back to their cells and put them in dropboxes in their pod later.

Republican Garfield County Sheriff Lou Vallario said he thought a lot of people in the jail would be interested in voting, it was just a question of figuring out the logistics to maintain security.

For instance, no pens were allowed to be used, and the ballot blue book was only available online on the jail-issued tablet.

“Every time anybody comes into jail, whether you come in to visit or they do, we have to be concerned with safety and security and how inmates respond.”

He said it’s manageable.

“And so there were some things that were unique because we were basically allowing something new to sort of penetrate our walls if you will. But certainly in our jail, we're comfortable with how we worked it out with our clerk and recorder, and safety's not an issue,” he said.

Vallario said the vast majority of people in his jail, which is usually around 60-70 people, are not serving a felony sentence, so under the law, they’re legally entitled to vote. In fact, he said most of them are pre-trial.

“They're still innocent. They haven't been proven guilty of anything. They certainly are constitutionally entitled to vote, and I support that.”

CPR News' Kiara Demare contributed to this report.