The woman was cowering between two houses next to a man who had been shot by Denver police, as more than a dozen officers moved in.

They believed it was a hostage situation, though it was later discovered the two people were faking it to elude arrest. The man, who was shot by police, was conscious. The woman was loudly crying and shouting. It was the middle of the night. Both had blood on them.

More police cars arrived. The orders were coming from multiple officers standing, with guns drawn, around the front lawns and the driveways of the two homes, according to body camera footage shown from an August 2023 incident.

“Female, put your hands on your head!”

“Female, crawl to me, keep coming, crawl to me.”

“Show me your hands!”

“Keep them on your head!”

“You need to come here or we’re not going to help you.”

The shouting did not achieve the desired result. Crying, the woman went from panicked to hysterical as officers shouted that litany of commands at her in the space of abut 80 seconds.

She wailed and stayed near her injured friend. The officers continued.

“Back away from him!”

“Get away from there!”

“The quicker you listen to us, the easier it will be to get him help.”

“Female, come to us, now.”

With the ubiquity and availability of body worn camera footage produced by law enforcement in recent years — Colorado required it of all officers in a state law passed in 2020 — one thing has become painfully clear: Communication in law enforcement matters, and when delivered in mixed messages contribute to less than ideal situations.

“Body cameras show us exactly how officers communicate with the public. It’s no longer a written report, it’s exactly how they interact with people, how they stop a motorist, how they give a ticket and then it expands to a whole series of use of force situations,” said Chuck Wexler at the Police Executive Research Forum, a research and policy organization that provides management help and training to support law enforcement agencies.

“The one word that is so significant in all of this is communication. How you talk to people, how you communicate, how you respond makes such a difference,” he said.

Police have increased their training on how they talk to people. Since George Floyd’s murder in Minnesota in 2020, Colorado has implemented emotional intelligence training for officers. Organizations like Wexler’s have built modules for communication and deescalation in the last four years in hopes of improving the way officers deal with distressed people in critical moments.

Yet there are contradictions.

Assigning lead communicators

Because police are also trained — both in academies and the lived on-patrol experience — that even the most predictable of stops or calls for service can end in someone pulling out a gun.

Ira Cronin, who works at the Colorado Springs Police Department, said even routine traffic stops have to be approached carefully.

Because it could be a man who just committed an armed robbery trying to get away or it could be a mom running late to work after dropping her kids off to school, he said.

In critical incidents, Cronin said CSPD officers train for there to be a lead communicator, usually the one who is first on the scene, who is supposed to take charge of working with a suspect.

But Cronin noted, “We can only train for half of the equation.”

“Things are happening in every officer’s mind on that scene,” he said. “If things start happening really rapidly with the suspect and other officers are on the scene, now there are more people making split-second decisions.”

Adams and Broomfield District Attorney Brian Mason has seen hundreds of hours of body worn camera footage in his career as a prosecutor. DAs are ultimately responsible for deciding whether officers are criminally charged when they injure or kill someone on duty.

He said, up until someone pulls a deadly weapon out, the tone from officers does matter.

“It will often begin with, we just want to help you, we just want to get you to the hospital or get you the help that you need, we just want to talk to you,” Mason said. “In the best case scenario, that kind of tone, that ‘we’re here to help, we’re not here to hurt you’ works the best.’”

But when things turn, it’s usually because of the suspect, he said.

“If the suspect is armed and dangerous, the objective of the police officers is to protect the community, to protect the surroundings and to protect themselves, to some extent, and also to try and resolve it without the suspect getting hurt and that can be a chaotic situation,” Mason said, noting when he sees a suspect armed walking toward police with a gun or a knife, officers are trained to get collectively get him to drop the weapon. This can include a lot of screaming.

“In those situations, the officers on scene are usually all screaming at the guy and that’s because the person is presenting an ongoing threat.”

Mason added, “Hearing commands from multiple officers may be confusing but I don’t know of a better way to do it.”

‘No, no, no, I put it down’

In Lower Downtown Denver earlier this year, officers were called to a parking lot on reports of a fight. Passersby told officers that a guy in a white Audi had a gun. They broached him and the guy opened his driver side door in a parking lot.

“Let me see your hands!” the officer yells. “Let me see your hands right now!”

The man raises both hands at shoulder level above the car window. His left hand is empty but his right has a semiautomatic handgun, held loosely, pointing at the ground. Two seconds later, the same officer yells, “Put it down!” A number of other officers begin yelling commands, all in a matter of seconds.

The man shifts the gun, still held loosely, to his right hand, and one officer fired a single shot, hitting him in the bicep. When they cuffed him, he told them, “I am not a criminal, I am not a criminal. I was just trying to save myself.”

The officer, who was ultimately not charged in the incident, said, “You just tried to a point a (expletive) gun at me, dude!”

He responded, “No, no, no, I put it down,” he said. “Sorry. Sorry about that, mate.”

When standoffs go wrong

In standoffs, or even hostage situations, where officers don’t feel like anyone’s life is in imminent danger, they’re usually trained to assign a single communicator to the person in distress.

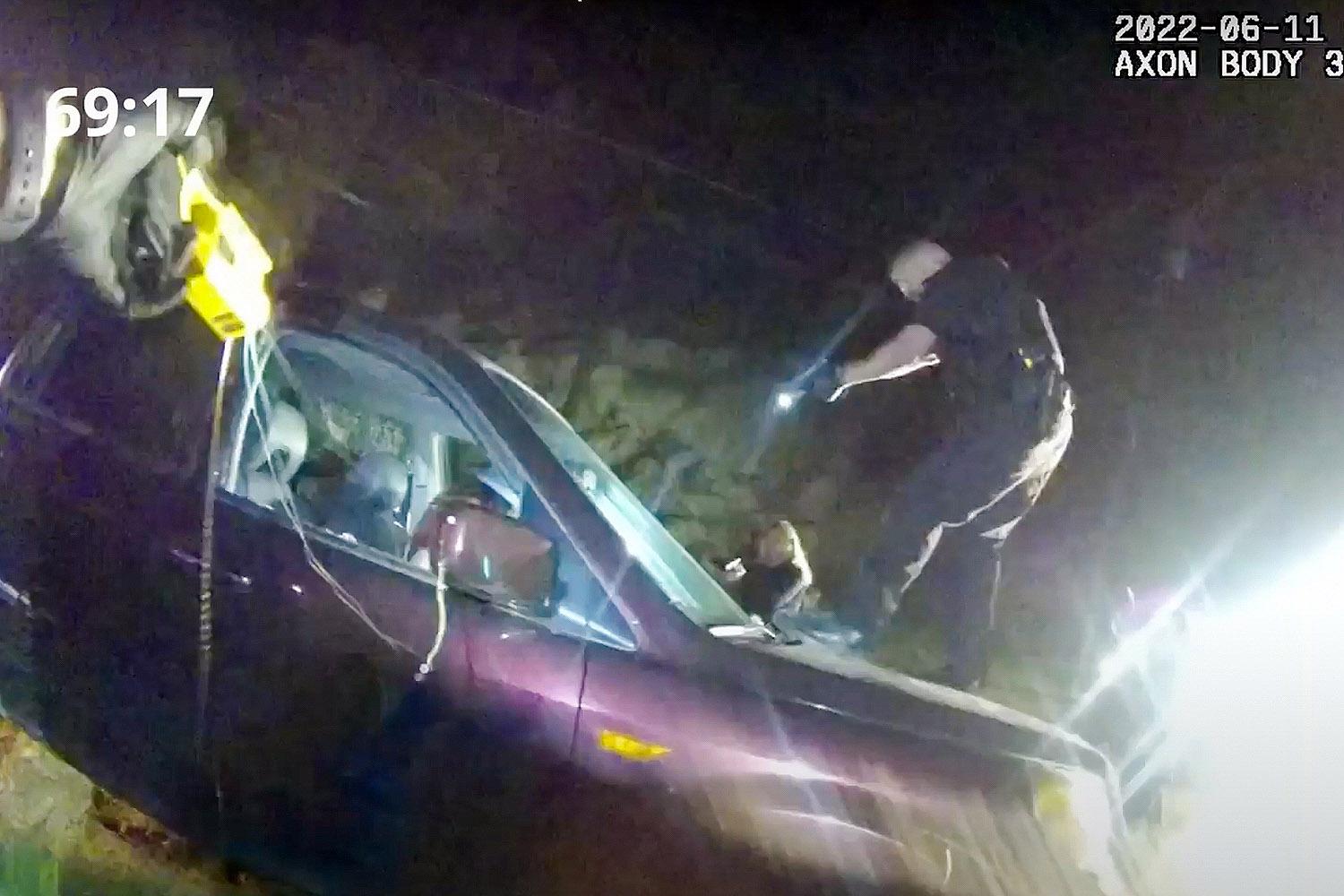

This is the opposite of what happened in June 2022 with Christian Glass in Clear Creek County.

Two sheriff’s deputies responded to a call for service from a scared man who had crashed his car into some rocks on a mountain road. Glass, 22 at the time, told a dispatcher that he had two knives in the car from a geology trip, as well as a rubber hammer, meant for rocks. He offered to throw the weapons out of the car when officers arrived, so they wouldn’t assume he was dangerous.

Clear Creek deputies arrived angry and within a few seconds demanded that Glass get out of the car. When he said he was scared, they escalated the situation. He again offered to throw the weapons out of the car, but they refused. After more than an hour and many additional officers from various agencies arriving on the scene, all screaming at him, the lead deputy ultimately shot and killed him.

Lawyers who represent people in civil suits against law enforcement agencies say that communication matters — even during critical incidents.

Qusair Mohamedbhai represented the Glass family, who sued the Clear Creek County Sheriff’s Office and several other agencies after their son was killed. They ultimately won a $19 million settlement with the counties involved and a half dozen officers on the scene that night faced criminal charges.

“The solution is fairly obvious that there is some coordination with law enforcement ahead of time as to who is going to communicate and what the expectations will be,” Mohamedbhai said. “People shouldn’t be put in a position where if they don’t make the absolute perfect decision in a highly stressful moment, they die. Police shouldn’t create a situation where a flinch or a hand going up or down and they die. They shouldn’t create the exigent situation where they then use it to create the excuse to use deadly force.”

In addition to the monetary part of the settlement agreement with the Glass family, Clear Creek County agreed to additional training for all of its deputies in crisis intervention and treating people in mental health crises with professionalism and empathy.

Glass’s mother, Sally, told CPR News in an earlier interview that officers should have treated her son appropriately for how he was acting while locked in his own car: scared.

“He was really scared. He was cornered and he was being terrorized and bullied, and he was in a dark place that he didn’t know and was surrounded by men pointing guns at him, who he thought was going to help him,” Sally Glass said.

Across the country in Washington, D.C., Wexler uses the Glass body worn camera footage for training at the Police Executive Research Forum’s ICAT, or Integrated Communications Assessment and Tactics training, for officers from around the country.

“We absolutely use that video in training, look at what that officer did? Look at how he’s communicating. Look at his tactics. Look at the person in the car,” he said. “We want to show, we want to say, think about this person in the car. Think about this person’s parents. This person is in crisis. What is the threat?”

- Christian Glass’ family hopes their settlement will spur law enforcement not just to apologize, but to reform

- Colorado voters come full circle on supporting – and refunding – police

- As an investigation into a Thornton Police shooting continues, a family awaits answers

- Las Animas County reaches $1.5 million settlement with man tased in face by deputies