This story is part of CPR News' Cash for Caring series. Read the first installment here.

Yevgeniy “Geno” Shvedov said he first got the idea to own a chain of sober living houses in 2016.

At the time, he just as easily could have been living in one.

Shvedov, 36, a mixed martial arts fighter known as “The Russian Concussion,” may not have been ready to get sober. He was caught dealing drugs during one of his prison stints. When the idea came to him, he was facing the possibility of parole revocation. He hadn’t yet been arrested for unlawful sexual contact - that would come a little later.

But fewer than five years after what he says was an initial brainstorm, Shvedov’s company received the first of what would become more than $2.7 million in payments from Denver taxpayers.

Shvedov now oversees both ParadigmONE and Hazelbrook Sober Living, one of the largest sober living operations in Colorado. According to a 2022 Department of Corrections contract, his company listed 26 sober living homes — two in Denver, 13 in Aurora, and houses from Colorado Springs to Pueblo. Since then, the company has almost doubled in size, to about 40 homes.

Unlike Hazelbrook Sober Living, ParadigmONE is a nonprofit operation, and the recipient of the Caring for Denver grants to fund services in homes operating in what Shvedov calls the “Transitional Safety Zone.” In that program, which Shvedov says he invented, people in sober living are able to test positive for drugs and remain housed. Residents receive support services, including boxing classes at Shvedov’s Aurora gym.

“Our programs promote constructive recovery outlets such as boxing, martial arts, fitness, yoga, art, music, recovery coaching, life skills training, spiritual mentoring, and sober gatherings and events,” reads a 2022 application for grant funds from Caring for Denver.

ParadigmONE is just one of more than 200 grantees who have received Denver taxpayer funds through Caring for Denver, a sales tax approved by Denver voters in 2018. Since 2020, Caring for Denver has granted more than $170 million, mostly to nonprofits.

A year-long review by CPR News found that while grants went to some of the city’s most established mental health and drug treatment providers, tax money was also given to companies with no history or license to provide behavioral healthcare, and to some companies run by individuals with lengthy criminal histories.

People like Geno Shvedov.

About six months after ParadigmONE got approval for the first of three Caring for Denver grants, its sister company, Hazelbrook Sober Living, purchased a nearly $1 million Denver home in a tidy neighborhood off Hampden. But it is not used for sober living. Shvedov said he and his wife live there.

It’s unclear how exactly Shvedov is paid. He said that his paychecks come from Hazelbrook Sober Living, not ParadigmONE. But in three years as executive director of ParadigmONE he reported to the IRS that he worked 40 to 50 hours a week at the nonprofit, with $0 in compensation last year. He lists a total of $17,056 in salary from 2021 to 2022.

When shown the public tax form, Shvedov couldn’t explain why the line for his compensation last year was blank. His wife, ParadigmONE’s director of operations Jess Shvedov, signed the 990 tax forms, but couldn’t explain why she had no salary listed. Caring for Denver’s executive director Lorez Meinhold told CPR News that Shedov’s accountant made a mistake and would file a corrected form.

Shvedov has a long criminal history, including assaults, burglaries, and trespassing. In 2007, at 19 years old, he was arrested for first-degree assault for allegedly throwing a brick at a person’s face in a suburban neighborhood in Centennial. The victim was “found outside lying on the sidewalk with a brick near his head, with multiple fractures to his face.” A female witness reported to police that Shvedov’s mother, Alexandra Shvedov “did try to offer her money not to call the cops,” according to the arrest affidavit. The case was dismissed.

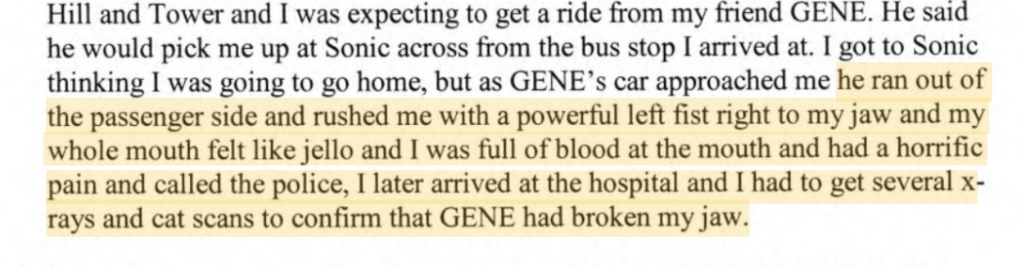

About six months later Shvedov broke the jaw of someone whom he claimed stole his CD. The victim said he was blindsided by a powerful punch from Shvedov, and that his injury would require surgery. A doctor at University Hospital in Aurora signed a serious bodily injury form for police to put in the case file.

Arrests and convictions followed for assault, a domestic violence protection order violation, trespassing, and drug distribution. Shvedov racked up 14 violations in prison for violence, gambling and drug dealing, according to a 2016 presentence report.

In 2017, he was on parole when he was arrested for a misdemeanor, “sexual contact - no consent,” against a woman in Denver who also works in the sober living industry. He maintains that the charge was the result of a false accusation. He was acquitted by a jury about two months before Caring for Denver began collecting signatures for their ballot measure in 2018. Even Denver District Attorney Beth McCann, who sits on Caring for Denver’s board and whose office prosecuted that case, voted for ParadigmONE to receive the grants.

“As far as I’m aware, Hazelbrook Sober Living has been a very worthy grantee and there have been no issues with the way it operates or with the people in charge,” McCann said in a statement from her office. “With respect to the case brought against (Shvedov) in 2017, he was found not guilty of that charge.”

While Shvedov was working through his parole, records show his mother, Alexandra Shvedov, was beginning to build the sober living business, signing the first in a series of contracts with the state, in 2018, to house people on probation. In 2020, she signed a contract with the Colorado Department of Corrections to house parolees coming out of prison. Geno Shvedov began signing the DOC contracts starting in 2021.

Geno Shvedov dismisses the unlawful sexual contact case as an attempt to smear his name. But he readily admits the rest of his long criminal history, and blames substance abuse. A tattoo running the length of his left forearm says “Let the past create the future.”

“Geno is not funded in the grant,” said Meinhold, emphasizing that Caring funds organizations, not people. But she added: “People with lived experience are such an important part of this work. It is what helps people come to recovery where they feel supported and safe.”

Meinhold said that Caring for Denver funds ParadigmOne’s “work in Denver and some of the transitional houses in Denver.” The Caring for Denver tax money can only be spent on Denver residents. But records show, and Geno Shvedov confirmed, that his transitional homes are all in Aurora. When informed by CPR News that the transitional houses are not in Denver, Meinhold asserted that only Denver residents in those homes received programming with Caring money. Shvedov said the same.

Meinhold said a third-party review of ParadigmONE and Hazelbrook was conducted into the finances of the nonprofit and how money moves between it and the for-profit. The review found no issues, she said. But Meinhold refused to provide CPR News a copy of that review, or any other internal audits conducted by Caring for Denver, saying nondisclosure of “internal audits” was standard practice of city and state agencies. Colorado’s Open Records Act, however, does not exempt reviews or audits from public disclosure by government entities.

The finances behind Shevdov’s operation are complex. In an interview, Geno and Jess Shvedov both claimed to not know much about who owned the dozens of homes in their program. CPR identified ownership records for more than 20 of the houses. His mother owns several. One, where Caring for Denver funds programming, is owned by a corporation registered in Belize, where ownership records are not public. Shvedov at first said he didn’t know who owned the Belize corporation: “I’m not sure, I think it’s an investment company.”

But when CPR News showed him records linking the corporation to his father’s address and asked him if his father owned it, Shvedov said “I think so.” IRS tax forms also show that last year the nonprofit paid his mother’s company called “Hazelbrook LLC” $276,850 for “facility rental.”

“You have kind of a tangled web of transactions between influential people in the organization and family members and properties owned by family members,” said professor Brian Mittendorf, an expert in nonprofit accounting at Ohio State University. “That complicated web is one that an organization would be wise to draw very fine lines about, and make clear to the public and the grant provider that none of the money is being intermingled in ways that are benefiting people instead of benefiting the cause.”

Shvedov’s business network has become increasingly complex this year. Shvedov registered several new for-profits in 2024: Hazelbrook Franchise, LLC, Hazelbrook Metro LLC, Oakwood Behavioral Health LLC which operates under the trade name Hazelbrook Behavioral Health, according to Secretary of State business records.

In a text message, Shvedov said everything he and his companies do is above board.

“The funding that Caring4Denver provides is received by a Fiscal Sponsor and then when dispersed to our organization is highly monitored and accounted for on multiple levels including internal financial specialists, 3rd party financial audits, a fiscal sponsor, Caring4Denver, and a board of directors,” he wrote in a response to questions.

Shvedov, who spent time in sober living while recovering from his own addiction, holds no state licenses in behavioral or mental health, though he says he is a certified peer recovery specialist. He has a 3-3 record as a pro MMA fighter, and is licensed by Colorado as a corner man for boxing matches.

Shvedov said his program is highly effective at getting people off drugs.

“We have a very large number of successes that have been able to maintain 90 days plus of sustained sobriety,” said Shvedov in an interview with CPR News. “Which not only is incredibly impactful in those individual’s lives, but as far as saving the City of Denver money, saves tons and tons of money.”

He admitted though that it’s largely unknown what happens after three months.

“After they leave our care it’s difficult to track a lot of times if they're gone we do try to stay in touch,” Shvedov said. “We do have an alumni program where we try to stay in touch with individuals, but it’s hard to stay in touch with people if they're gone, we do our best.”

Jess Shvedov added that Caring for Denver is more thorough than other grantors. “I have probably more follow-up meetings with them than I do other grantors, to talk about where we are, who's being served, what are the outcomes of this.”

Geno Shvedov declined to answer further questions or provide any documentation to CPR News.

Caring for Denver and its board chair, State Rep. Leslie Herod, both emphasized that Colorado’s Behavioral Health Administration also awarded grant money to ParadigmOne. BHA provided the full file to CPR News, including score sheets showing ParadigmOne had one of the highest scores among grants that cycle. ParadigmOne attached a series of letters of recommendation for the grant application.

The first letter was a strong endorsement from Caring for Denver.

An anti-violence program, and a murder charge

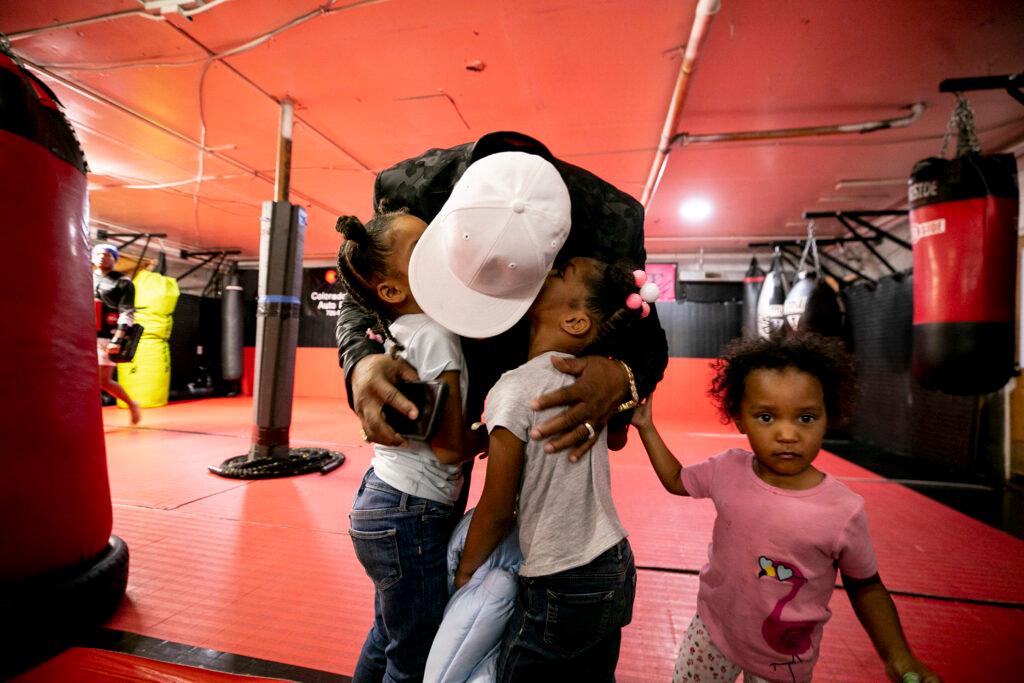

Heavy Hands Heavy Hearts describes itself as a “nonprofit committed to improving public safety to reduce the impacts of violence in Denver’s urban communities.” It was created and run by another MMA fighter, Lumumba Sayers Sr.

Sayers is currently in the Adams County jail facing a murder charge.

Sayers was granted a total of $458,448 over two grant cycles by Caring for Denver to provide, among other things, “Recreational therapeutic activities,” including boxing and art therapy, and possible employment in his moving company (the moving company license for “Sayers Citywide Movers LLC” expired in 2015).

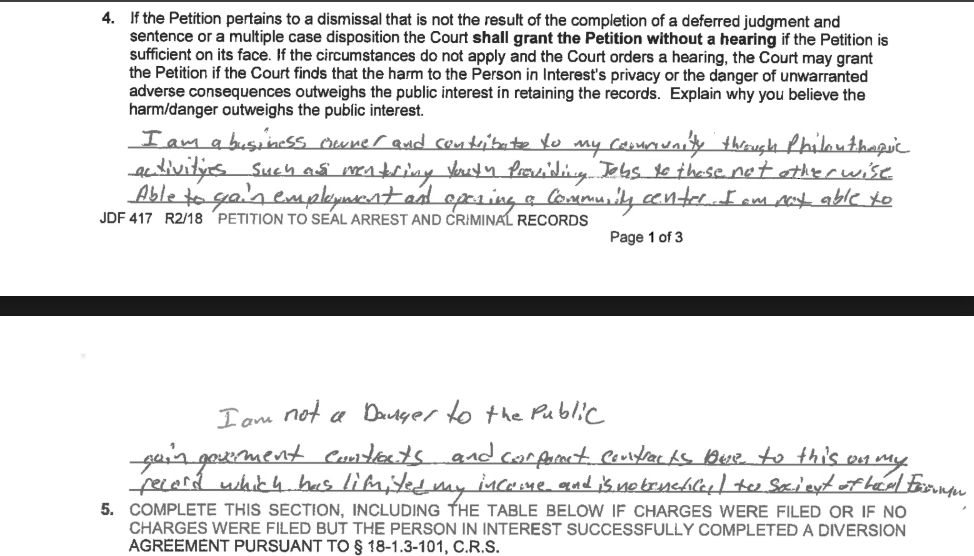

Sayers also has a criminal past, which includes domestic violence charges. Sayers unsuccessfully attempted to seal his records so he could, in his words to the court: “gain government contracts.” It turned out he didn’t need to get them sealed to obtain grants.

The second Caring for Denver grant funded Sayers’ “Glovez Up, Gunz Down Movement program” to “instill resilience in Black and Latinx youth and adults to teach them healthier ways to avoid, reduce, or stop engagement in high-risk behaviors,” according to Caring for Denver’s 2022 annual report.

Sayers’ son, who worked at the nonprofit, was shot and killed in 2023, and this summer, police investigators say Sayers shot and killed a man in a public pool parking lot in Commerce City. Sayers has pleaded not guilty to the charge of murder and his preliminary hearing is scheduled for next year.

“We fund the organization, and the organization was an organization in good standing,” said Meinhold.

The organization, though, listed only one employee, Sayers, on its 2021 IRS tax form when the first Caring for Denver grant was awarded.

Heavy Hands Heavy Hearts, Meinhold added, “has shown that they can work with youth well, and really worked on this anti-violence and how do we heal in trauma.” She said that the U.S. Department of Justice has vetted and also invested in Sayers’ program. Heavy Hands Heavy Hearts was also awarded $250,000 from the Colorado Department of Public Safety in 2023.

It’s not clear what evidence Meinhold relies upon in vouching for Heavy Hands Heavy Hearts' success rate. Sayers, who holds no state licenses in mental or behavioral health, said on his grant application that “participants will indicate an increase in making positive life choices and engaging in healthy activities and relationships.”

Meinhold said that since Sayers’ arrest, another person is taking over programming for Heavy Hands Heavy Hearts. On a recent fall day, the small building was unoccupied and a neighbor said no one had been there since Sayers’ arrest.

Figuring out what programs actually reduce violence has become a major project for former Colorado U.S. Attorney Bob Troyer. He’s convinced that there’s a role for community groups in reducing violence among at-risk youth, and the longtime prosecutor wanted to get involved with a program after leaving the Justice Department.

“So I started researching and learning as much as I could about this industry, to find what worked, so that I could throw in with whatever that was,” said Troyer. “And what I learned instead was no one knows what works.”

Troyer and two criminologists at University of Colorado, Denver have developed a survey and tracking instrument to measure the effectiveness of anti-violence programs. They are currently conducting a pilot study with Lifeline, another Caring for Denver grantee, to test the instrument’s effectiveness. There are no results yet.

A Denver center with a California therapist

The Denver Dream Center is a church that also feeds unhoused people from a large warehouse downtown. Bryan “Pastor B” Sederwall was granted $693,039 in two Caring for Denver grant cycles to hire a behavioral health clinical director and launch counseling services.

Sederwall’s staff told CPR News that they hired “Dr. Tray McVay” to be clinical director for the first year of the grant.

“And he’s incredible,” said Jen Sanders, program director for Denver Dream Center. “He met with everybody. Did all the clinicians, all, like you know, the classes, and reviews and whatever.” She had difficulty recalling exactly what McVay did.

But CPR News could only find a Trayvonne McVay licensed to work as a psychological associate in California, and he did not respond to requests for comment. No one licensed in Colorado matches that name. Follow-up questions to Sederwall and Sanders were not returned. Caring for Denver said McVay never provided clinical services, “just peer supports, navigation, and he developed an interdepartmental referral process for youth to be connected to care.”

The Denver Dream Center eventually contracted with Harvest Therapeutic Services to provide mental health counseling. The owner of that organization hung up on CPR News when asked about their work with Denver Dream Center, so that contract could not be verified.

Sederwall and his staff couldn’t provide the number of people served by the grant during an interview. They said they would email that information, but never responded to CPR News again.

“You’re throwing people's records in their faces, and that's getting around the community,” said Herod, in an interview with CPR News. “It's making people feel like they're being attacked.”

But Herod was also unable to answer some questions about grantees with troubled pasts or who may have overstated their qualifications.

“There are some issues that have been raised that are concerning,” said Herod after being briefed on CPR News' reporting. “And I have asked questions about them and we will continue to ask those questions.”

Herod said she has personally seen the Dream Center’s therapeutic teams in action and has met people who have been served.

Caring for Denver featured Denver Dream Center in its latest annual report and promoted a local TV news report on the organization. Meinhold was quoted in the CBS Colorado story, standing in the Dream Center facility downtown, touting Caring for Denver’s financial support of nonprofits providing quality care.

Sederwall has never filed a public tax disclosure for Denver Dream Center, claiming he doesn't have to because he’s a church, but Sederwall said he would file one in the coming year.

In response to CPR News' findings, Meinhold said in a statement that the Dream Center “has struggled during the period of our grant, and we have been disappointed in the results to date.” She added that they would be unlikely to grant the organization money for a third time.

Herod said Caring for Denver doesn’t claw money back from organizations that are unable to fulfill their grant obligations. “We are not a clawback organization, I don’t even know that we can legally do that,” but she said there is accountability for underperforming nonprofits: they may not get grants in the future.

Where is Star Girlz?

Star Girlz was started by Shalonda Haggerty to help mentor and support young women caught up in the criminal justice system. It received three rounds of Caring for Denver grant money, totaling more than $1.2 million.

“Time to SHINE” Alternatives to Jail, will focus on providing unique and culturally centered substance misuse and mental/behavioral health services to 90 girls currently involved (court-mandated, probation, pretrial) or at risk (school suspension, homeless, etc.) for engagement in the justice system,” according to a 2022 grant application.

Formed in 2014, Star Girlz is run in coordination with Lumumba Sayers’ nonprofit, Heavy Hands Heavy Hearts, and, on state records, was headquartered in the same building.

Until Sayers’ arrest, youth in the two programs are said to be referred to one or the other depending on their particular needs, according to grant applications to Caring for Denver. After Sayers’ arrest in August for murder, Haggerty briefly took over his nonprofit as an interim executive director. She's still listed in that position on the Heavy Hands website, but Caring for Denver said someone else is now filling in for Sayers.

Haggerty formed Star Girlz in Colorado four years after she pleaded guilty to felony fraud and received a deferred judgment in her home state of Texas in 2010, in a case involving food assistance. Before getting Caring for Denver grants she had filed only one IRS tax return for Star Girlz, for 2016, showing just $5,502 in revenue. Meinhold said that Caring for Denver asked for additional financial statements before granting money to Star Girlz.

Haggerty is listed by state regulators as an “unlicensed psychotherapist.” Colorado was one of only two states that allowed people to practice psychotherapy without licensure as long as they registered with the state. That ended in 2020, but Haggerty and others were grandfathered in after a change to state law, which mandated licensure for any new therapists.

Haggerty has a masters degree in marriage and family therapy, and she claimed in her email signature as recently as last week to currently be a candidate for state licensure as a marriage and family therapist, but CPR News found that designation expired two years ago according to records at the Colorado Department of Regulatory Agencies.

Meinhold said Haggerty’s credentials are sufficient to provide mental health care as a Caring for Denver grantee.

“Our view is that unlicensed psychotherapists absolutely can provide quality healthcare in our state,” Meinhold said.

Experts in the field said that’s not always the case.

“That's something that's concerning for the psychologists in the state,” said Dr. Rick Ginsberg, the former president of the Colorado Psychological Association. “It’s a case-by-case basis in terms of what people can provide and do and what their training is, however, we feel there are certain safeguards in place through the licensure process that protect the public as well as the practitioner quite honestly.”

Haggerty said she also partners with a licensed therapy practice on some cases. In an email, Haggerty declined to be interviewed and threatened legal action against CPR News.

Also in that email, she acknowledged that her marriage and family therapist candidate (MFTC) license had expired. Yet even on that email, her signature included “MFTC” after her name. Haggerty, who also goes by the last name Palmer, lists MFTC after her name on her LinkedIn account.

Haggerty told Caring for Denver in grant applications that she would receive referrals from the Denver District Attorney and Denver Police Department for youth into her “psychoeducational” programs, but the DA’s office said no referrals were made, and DPD confirmed only one referral.

Haggerty also asserted that Star Girlz had a contract in place for referrals from Denver Human Services, but a spokesperson for the department said they had no record of that. State courts said it has contracts with Star Girlz in several judicial districts in the metro area, but not for Denver. (Caring for Denver taxpayer grant money must only be spent on Denver residents.)

On an October day, there was no one at the Star Girlz office on Dayton Street in Aurora when Caring for Denver-funded classes were supposed to be in session, and neighbors told CPR News that no one had been there since Sayers was arrested for murder in August.

When CPR News told Caring for Denver it couldn’t find Star Girlz, Meinhold wrote that Haggerty is now working virtually, and out of the Central Park Recreation Center while she looks for a new office. No Star Girlz classes or events are listed on the calendar for the Central Park Recreation Center.

Star Girlz has no new business address listed with the business licensure department at the Colorado Secretary of State’s Office, or on the website for Star Girlz. The organization continues to list programming at the Dayton Street facility on its published calendar of events.

Drug trafficking, domestic violence as 'lived experience'

From the Heart Enterprises is run by “Dr. Halim Ali” who calls himself a “mental health professional,” though he holds no licenses in Colorado. His organization received a total of $443,820 through four different grants to, in part, support youth seven years old and up, addressing “substance and mental/behavioral health issues.”

Halim Ali says on LinkedIn that he obtained his doctorate from “Sacred Olive Groves,” a university CPR News couldn’t find. Caring for Denver later told CPR News that Ali actually holds an honorary doctoral degree in public service from the Denver Institute of Urban Studies and Adult College, which maintains no website.

“Dr. Ali is practicing within his certifications,” said Meinhold, adding that his certifications are in “Youth Mental Health First Aid, Adult Mental Health First Aid and Five Protective Factors.”

In 2014, he was arrested as part of a large federal takedown of a drug trafficking ring. “Make no mistake: As a result of these raids, Colorado is a safer place,” said then-U.S. Attorney John Walsh following the arrests. Ali later pleaded guilty and was sentenced to time served and probation.

A year before receiving Caring for Denver grant money, Ali was accused in a 2020 request for a restraining order of multiple instances of domestic violence starting in 2017. A hearing in the matter was held, according to state records, but a restraining order was not granted, and Ali was never arrested for domestic violence.

Ali initially agreed to an interview, but then stopped returning calls and text messages.

Meinhold said Ali’s criminal record does not disqualify his company for grants. “And again people with lived experience are better to connect with individuals, better able to support them, there's a sense of safety,” said Meinhold in response to questions about Ali.

His grant paperwork says that From the Heart has two employees, a chess club and that it facilitates group and individual support to address drug and mental health issues. According to Caring documents from March 2024: “In the past year, the organization has connected 50 people to mental health and/or substance misuse support. 50% of respondents indicated a reduction in substance misuse.”

Fitness and mental health

In an application to Caring for Denver, ViVe Wellness’s executive director said the organization would convene community workshops with a “trained therapist, psychologist & with community.”

The organization received $921,438 over multiple grants from Caring for Denver, but director Yoli Casas acknowledged that Vive doesn’t actually have any licensed professionals on staff.

“No, we’re not a behavioral health person, the whole idea is to open up places like that,” Casas said in an interview. “We're not about a traditional mental health therapist.”

Caring for Denver, however, insisted that ViVe has licensed staff. Meinhold told CPR News that ViVe has “a licensed clinical social worker as part of their team,” and that ViVe’s clinical work is led by a trio of mental health professionals. Meinhold provided the names. One is a family medicine doctor in New York City, unlicensed in Colorado. That person did not respond to requests for comment. One is a “life coach” with no licensure. And the other, Marinela Maneiro-Goodwin, is also not licensed to provide services.

Meinhold then said there are two other licensed therapists who provide care at ViVe: Beatriz Blum, a marriage and family therapist licensed in Colorado, but who on her state profile says she no longer practices under her license. And Angela Calderon, a licensed professional counselor who works in Pueblo. Neither list ViVe as their employer on state records.

“I didn’t do it through ViVe,” said Calderon, when asked by CPR News if she had any connection to ViVe. “I think it was a grant-based program from Boulder, and I offered services to just Boulder residents, but not through ViVe.”

Calderon later clarified by text that she received referrals from Maneiro-Goodwin, who is listed as a support employee at a Boulder high school in addition to her work with Vive.

“I am not in a capacity to clarify more,” Calderon added by text, declining to respond to follow-up questions.

Maneiro-Goodwin is ViVe’s “Social-Emotional Support Program Coordinator.” She’s also listed as the independent study coordinator at New Vista High School in Boulder.

In text messages, Yoli Casas said that Maneiro-Goodwin works at ViVe a day and a half a week, and also works virtually. Casas took issue with CPR News' focus on licensed providers, saying the Caring for Denver grant to ViVe only anticipated $4,000-a-year of it being paid to licensed providers.

“Our priority are the programs which we did amazingly and where we are focused on changing and decreasing stigma,” Casas wrote in a text message. “And we have!”

So what did Vive do with more than $900,000 in taxpayer funds?

Casas, a former triathlon coach, said ViVe provides art and exercise-based therapy, including yoga. In ViVe’s grant application, she said programming would also include knitting and breathing and teen mental health. She provides children’s art programming and has kept some of the drawings done by the kids in the program.

“You can see what it was like, the pandemic, how they share with them how it was all dark and then when they came out how it was all colorful,” said Casas. “And so it's a way, it is art therapy, on how they can talk about it and it was amazing.”

Vive’s staff is small. The organization’s tax returns show just two employees in 2020, and still just four employees in 2023, when Casas said she was working about 80 hours a week. But while her staff has not grown much, Casas’s salary has - rising from $45,377 in 2020 to $162,368 in 2023 after approvals by Vive’s board of directors, according to the tax returns.

Inconsistent claims on application

After the infusion of $1.2 million in Caring money, the executive director of the small nonprofit organization Colorado Circles for Change, Angell Perez, also got a big raise: from $88,415 in 2018 to $179,753 in 2022, the last year there’s a publicly available tax form.

In 2020, Perez told Caring she had a current partnership for referrals to her restorative justice program from the Denver District Attorney, but the District Attorney told CPR News that office hadn’t worked with Circles for Change since 2016.

Perez said in an email that, even though the DA stopped referring clients in 2016, when she wrote the grant application in 2020 she assumed the DA would continue to refer clients.

Perez got a $300,000 grant to expand her diversion program, including at Colorado Department of Human Services’ Lookout Mountain Youth residential facility, but a representative for CDHS said they could find only one confirmed instance when a youth was referred to the program. Perez refused to be interviewed in person, but wrote in an email:

“Because of issues beyond our control we were unable to get strong momentum going with programming in the facility because of continued COVID outbreaks and the facility continuously going on lock down because of disciplinary issues with residents. Because of this when the grant ended we DID NOT REAPPLY.”

Circles also said in their application to Caring that the organization had a partnership with “juvenile probation.” A state judicial spokesperson said there have been no referrals to Circles for Change since at least 2020.

“It’s concerning,” Donna Lynne, the CEO of Denver Health, said of the claims Circles for Change made on its grant application that could not be verified with government agencies. Lynne is a board member for Caring for Denver and Denver Health is also a recipient of Caring tax dollars.

“I don't condone that behavior at all. I don’t know if it cancels out some of the outcomes that we see, if they were getting patients or participants from someplace else.”

“I think that's worth us taking on, ‘us’ meaning the Caring for Denver leadership, taking that on as a ‘let's go find out if they're telling the truth or not,’” said Lynne.

Perez eventually stopped responding to CPR News.

The organization’s website currently lists several programs for youth with a focus on leadership or rites of passage, but all of them concluded in late May. On a related Facebook page, the organization highlights its arts and fashion programs that continued through the fall, taking youth through cultural pride exercises.

Another section of the site says the organization offers restorative justice programs to “provide an alternative to traditional punitive consequences found in the criminal justice system.” On its 2022 tax return, the most recent, the organization said 502 youth had been “served” in the leadership program that year at an expense of $506,853. Another 18 were served in the restorative justice program or healing circles at an expense of $581,700, or $32,316 each. Circles for Change listed seven employees and 20 volunteers on that return.

In its campaign for the tax, Caring for Denver focused on how it offered taxpayers a chance to provide high-quality mental and behavioral health care to Denver residents. Lynne said she was proud of the work that Caring for Denver has done, but argued the grants were never designed to outright solve the longstanding problems of mental health and drug addiction. “I don't think that there was ever a belief that you spend this money and everything goes away.”

Expanding diversity in the field

In an interview with CPR News, Herod noted that several of the grantees with licensure questions were run by Black and Latina directors and served people in those communities. She argued that it was important for people to receive services from providers who “look like them.” And she took issue with licensed behavioral health workers questioning those qualifications.

“They're saying that this is not quality care to people who never get access to care at all, at all,” said Herod.

Carl Clark of Wellpower said there are just five Black psychiatrists, 22 Black psychologists, and 134 Black social workers in the state of Colorado and that Caring was conscious of that when trying to diversify the recipients of grant funds.

“People do like to go to a place where it feels familiar with them in some way,” said Clark. “So if a Black person walks in, and there are Black staff there, it makes a difference to them.”

But Herod and Clark also acknowledged that changing the racial and ethnic makeup of Colorado’s mental and behavioral health workforce through scholarships and professional development was an option for Caring to work toward from day one. Only in the last grant cycle did the organization begin to work with a Denver university on workforce. And the grant to Metropolitan State University of Denver for social work programs, $812,864, is less than Caring has given to Circles for Change, Star Girlz or Vive Wellness for programs.

Caring has also given a little more than $280,000 to help fund a Latinx mental health workforce development program in 2023. Another $442,000 in 2021 was granted to Colorado Mental Wellness Network for “peer support professional and peer support supervisor training,” Herod said.

“We have had conversations about workforce,” said Clark. “And the conversation goes like this: ‘what good does it do to fund a psychologist position in this organization if there are no psychologists to fill it, right?”