Many cities struggle to manage Canada geese that flock into their urban parks and waterways. Few have dealt with the issue like Denver did more than five years ago.

After failing to shrink its goose population using non-lethal methods, the Mile High City opted to kill more than 2,000 birds in 2019 and 2020. It then worked with the U.S. Department of Agriculture to process the fowl into meat for local charities serving hungry families.

The park-to-table plan led to immediate pushback from residents and animal rights advocates, who claimed the strategy was cruel and undertaken without sufficient public input. It also kicked off a viral media frenzy big enough to earn a nickname: #Goosegate.

Denver resident Lizabeth Netzle didn’t pay much attention to the controversy. While she noticed fewer geese on walks around Washington Park, she figured tales of urban wildlife transformed into ground goose chili and shepherd’s pie were likely urban legends. “I just assumed the whole business about feeding the homeless was bogus,” she told CPR News in an interview after submitting a question to Colorado Wonders.

A USDA biologist in a kayak herds Canada geese towards an enclosure on the bank of Denver City Park's Ferril Lake, July 1, 2019.

As hundreds of Canada geese fill a temporary enclosure, USDA biologists cull them and place them on orange crates in City Park, July 1, 2019.

Netzle, however, has seen plenty of geese around Denver this fall and winter, which led her to submit a question: was the culling operation effective, or will the city soon explore further lethal control to tamp down its goose population?

Our journalistic forks and knives are ready. Let’s dive in.

'A phenomenal success story'

Canada geese weren’t always a standard fixture in cities and suburbs across North America.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, the hefty honkers dwindled as hunters decimated the population to protect crops and harvest meat. In 1918, Congress passed the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, banning anyone from capturing and killing a long list of migratory species without explicit permission.

Conservationists later nurtured remaining geese to stoke the population. In 1957, Gurney Crawford and Jack Glieb, state wildlife managers and waterfowl researchers in Fort Collins, obtained a clutch of goose eggs and conscripted hens to incubate them. After the birds hatched and multiplied, Gurney earned the title of “Father Goose” for helping seed a new gaggle in northern Colorado.

The task may also have helped convince thousands of geese to visit the Front Range each fall and winter. In a 1992 oral history, Gene Schoonveld, a regional biologist for Colorado Parks and Wildlife, said migratory geese once bypassed Colorado in their journeys between New Mexico and more northern habitats. By breeding geese in Colorado, he said wildlife managers established a population happy to return to the region’s increasing number of reservoirs and irrigation ditches each year.

“Not only did the geese come back. They also enticed all the migrants that used to fly over Larimer County to start wintering in this vicinity,” Schooveld said. “A phenomenal success story.”

Today, Colorado Parks and Wildlife estimates the Front Range hosts around 200,000 Canada geese every winter. Most of the count includes birds flying through the state along the Central Flyway, a well-established migratory route stretching from Texas to the Arctic along the eastern edge of the Rocky Mountains.

The total, however, also covers “resident” geese, which live in the region year-round to munch on landscaped turf and enjoy a habitat with a substantial lack of predators. Those non-migratory birds left Denver searching for options to control its goose population five years ago.

'A goose can poop a pound a day'

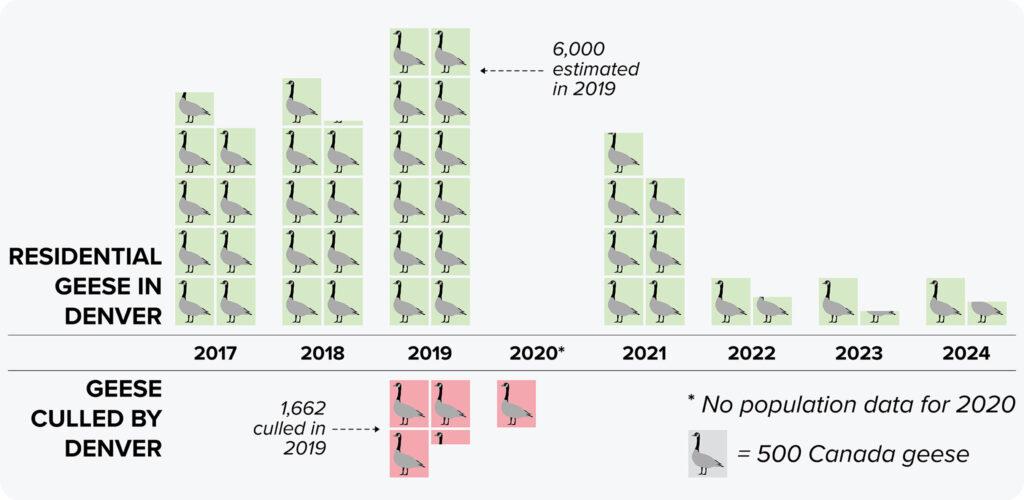

By the summer of 2019, Denver estimated as many as 6,000 Canada geese were living in its local parks year-round.

According to Scott Gilmore, the deputy director of Denver Parks and Recreation, the population frustrated some residents, who complained the birds denuded lakeside turf into mud slicks mixed with goose droppings.

“A goose can poop a pound a day,” Gilmore told CPR News at one of the first goose roundups in City Park. “It’s gotten to the point where people cannot enjoy the park because there’s so much goose poop out here.”

To tackle the issue, the city contracted the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Wildlife Services to round up geese during their molting season, when an annual feather shedding briefly renders the animals flightless.

Working before dawn, the federal agents used kayaks and remote-controlled boats to herd the geese off lakes, through a chute and into a temporary pen. The workers then stuffed the birds into crates, six at a time, before loading them onto trucks bound for a nearby meat processor.

CPR News and Denverite published the first reports on Denver’s goose-culling operation. The story kicked off a frenzy of further media coverage, which led reporters to gather opinions from park visitors and sample the meat served at food banks. Reviews were middling: greasy, kinda like ground beef.

While some residents applauded the city’s efforts, critics expressed horror at what they called “clandestine raids” on innocent wildlife. A citizens group called Canada Geese Protection Colorado organized rallies and put up billboards calling for an end to the culling campaign. Some protestors even brought “Goose Lives Matter” signs to former Mayor Michael Hancock’s inaugural address in 2019.

The city ultimately removed 2,179 geese in 2019 and 2020 through its partnership with the USDA. It opted against further cullings the next year, saying it had brought the population down to manageable levels.

'The culling was effective'

Vicki Vargas-Madrid, Denver’s wildlife program manager, now oversees the city’s ongoing efforts to control its resident goose population. Since the removal program ended, she said her staff has doubled down on non-lethal methods to contain the flock.

“I do believe that the culling was effective,” Vargas-Madrid said. “We are seeing a reduction in the population and the growth since we culled in 2019 and 2020.”

Denver’s official numbers align with the assessment. In 2019, the city estimated it had about 6,000 resident geese living in its parks through the summer. The most recent count found the population was down to 757 in 2024 — marking a nearly 90 percent decrease in five years.

It’s unclear what triggered such a sharp decline. Stephanie Figueroa, a city spokesperson for Denver, said the city would like to credit its multipronged strategy, which includes hazing, oiling eggs to prevent goslings from hatching each spring and altering landscapes to make parks less inviting to waterfowl.

Those efforts are now a near-constant focus for Denver parks staff. On a recent afternoon, Vargas-Madrid joined an employee at City Park to operate the “Goosinator,” a remote-controlled fan boat painted like a bright orange shark. Her team ran the contraption across Ferril Lake in a zigzag pattern to mimic a predator, triggering thousands of birds to take flights in terror. The hope is the strategy will encourage the geese to migrate out of Denver in a few months.

Focusing on non-lethal methods has helped repair the city’s relationship with its former critics. Carole Woodall, a founding member of Canada Geese Protection Colorado, now organizes park cleanups in coordination with the city. By making a positive contribution, she said her group hopes to sustain a conversation about how to build a “sustainable, multi-species environment.”

Vargas-Madrid said the city could reconsider further goose culling if the resident population suddenly rebounded. But, if there was any lesson learned from #Goosegate, she said the city knows to work with the public to explore all alternatives before proceeding with any plan.

“Our goal is to continuously use research and creativity to figure out how we can all coexist without having to go to lethal control,” Vargas-Madrid said.