A steering committee is now forming, and a leader is being sought, to meet the requirements of a bill passed last summer to research Colorado’s federal Indian boarding schools, part of a larger national movement to address the issue.

HB24-1444, the Federal Indian Boarding School Research Program, went into effect in August after being approved by Gov. Jared Polis in May.

It launches a research program to be run by History Colorado, which will “conduct research regarding the physical abuse and deaths that occurred at federal Indian boarding schools in Colorado . . . in consultation with the Colorado Commission of Indian affairs, the Southern Ute Indian Tribe, and the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe to develop recommendations to better understand the abuse that occurred and to support healing in tribal communities.”

In Colorado, the Ute Mountain Ute and Southern Ute are the two federally recognized tribes.

The act recreates the program, which had been repealed on December 31, 2023, and requires the general assembly to appropriate $1 million for three years. Its sponsors were State House Representatives Barbara McLachlan and Leslie Herod, and state Senators Jeff Brides and Cleave Simpson.

History Colorado is now doing two things to get the bill moving: finding a leader to handle the research, and forming a committee inclusive of survivors, to steer it.

Until last week, History Colorado’s website had a posting for the open job of senior director of tribal and Indigenous engagement to “direct History Colorado’s engagement with Tribal leaders, representatives, urban Native communities and other members of the Native diaspora connected ancestrally or contemporaneously to Colorado.”

The person hired will lead efforts related to the bill; “serve as a key team member in ongoing organizational compliance with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act,” build programs; co-author a report, and support preservation and repatriation efforts,” according to the job post, which says the job will be about three quarters research into Coloardo’s Indian Boarding Schools and will earn between $82,000 and $123,000 a year.

At the same time, History Colorado is creating a committee to steer the research, which is in its early stages.

“I would say we are beginning to move, but the work really hasn't begun as of yet,” said Noelle Bailey, senior director of equity and engagement at History Colorado in an interview this month.

She will be one of History Colorado’s staffers playing a leading role on the committee. Another, in addition to the new hire, will be Holly Norton, state archaeologist and deputy state historic preservation officer with History Colorado.

Bailey added the committee has met twice and is in the process of filling its roster.

“We are calling it the Colorado Boarding School Steering Committee,” she said, also describing some of the goals of the committee:

“So we're both doing the research of discovering where these schools were, if there is anything at these schools that may be belongings or they may be remains, and then continuation of collecting narratives and testimonies from family and individuals who went to these schools,” she said.

The commission has five open seats, according to Luke Perkins, a History Colorado spokesperson. Available are two spaces for survivors of Indian Boarding Schools In Colorado; one space for a descendant of a survivor; one space for a citizen of another tribal nation identified as having members enrolled at any time in an Indian Boarding School in Colorado, and one space for a trauma-informed mental health professional, according to Perkins.

Already 10 participants have been found.

“All of our members on the steering committee are members of, they're Native American. They're either within tribal society or urban, and we are still holding space,” Bailey said. The committee’s total membership will be 15.

“We want to have people that have lived experience of boarding school or are descendants of individuals, but they need to be centrally located within Colorado as we are doing research solely on Colorado schools and nothing outside of that,” Bailey said.

Boarding schools for Indigenous children that existed in Colorado include:

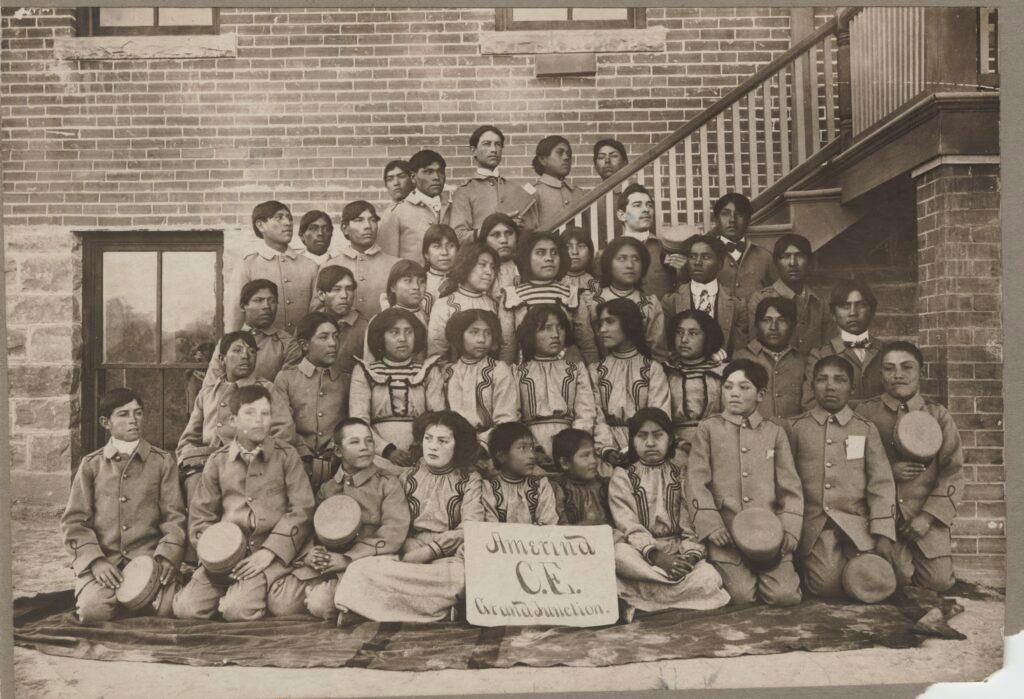

- Teller Institute, also called the Teller Indian School, operated from 1886 to 1911 and brought in children from across the west. A few years after the Teller Institute closed, the property became a state facility for housing people with developmental disabilities. It is now called the Grand Junction Regional Center.

- The Fort Lewis Indian Boarding School, which operated in Hesperus, was 30 miles west of the current site of Fort Lewis College, from 1892 to 1909.

Estimates of children who died at schools used to hover around 1,000 nationwide, but a recent investigation by the Washington Post puts the total at 3104, triple the previous estimate.

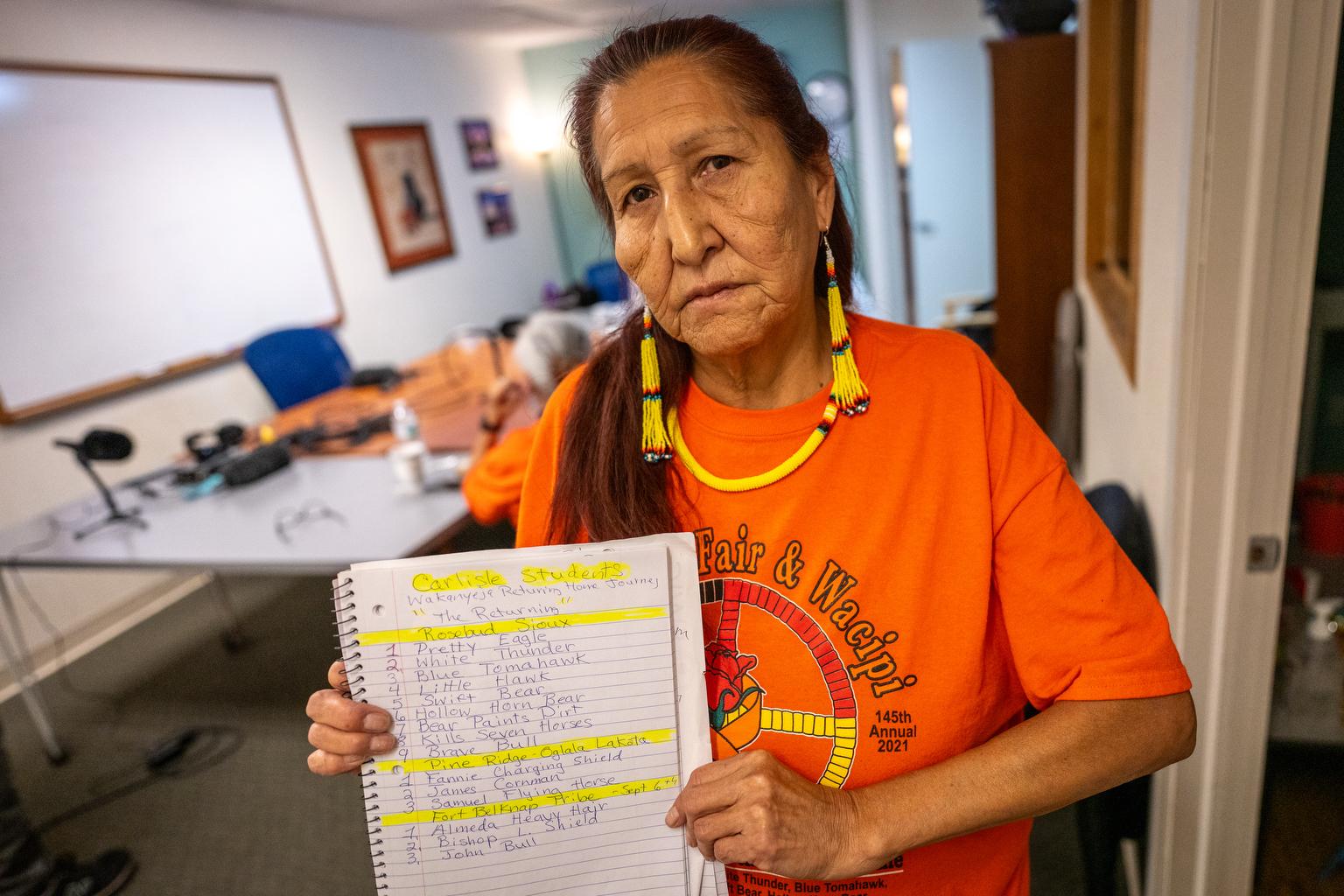

One of the members of the new committee who was forced to attend an Indian Boarding School in South Dakota and who now lives in Denver, is Ruby Left Hand Bull Sanchez. According to her and other local survivors, life was terrifying at boarding schools. She and other survivors report being assigned numbers in place of their names, being physically brutalized when they did not adapt American behaviors, having their braided hair cut off against their will, and their mouths getting washed with lye if they were caught speaking their native languages.

Some reconciliation efforts have happened in recent years. In 2019, Fort Lewis College began a “reconciliation process that acknowledges our historical impact and honors our responsibilities to Indigenous communities, students, faculty, and staff.” In recent years the school ceremoniously removed inaccurate signage about the school’s history and held listening sessions.

Nationwide, similar efforts have been made. President Biden apologized in October for the history of Indian Boarding Schools, which operated as recently as the 1970s, calling it a blot on American history during a 30-minute speech. “I formally apologize as President of the United States of America for what we did. I formally apologize,” he said to loud cheering. ‘It's long overdue,” he said.

His apology followed the Department of the Interior publishing an investigation into the assimilation effort, part of the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative, which also involved visiting some of the school grounds in 2023, and a report that detailed the scope and impact of boarding schools, which had come out a few months before the apology, in July, 2024.

Left Hand Bull Sanchez said Biden’s apology meant nothing to her because it didn’t come with any form of recompense, and did nothing to undo her experiences in the boarding school that took from her her ability to speak her native language, dance or in any way celebrate her cultural heritage and caused her to battle with alcohol for years to tamp down the memories of being traumatized and unsafe.

Besides Biden’s apology, other efforts are being made to acknowledge the effects of boarding schools. The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, based in Minneapolis, has a cooperative agreement with the Department of the Interior to conduct video interviews with Indian boarding school survivors “to create a permanent oral history collection.” It is seeking participants who can sign up at the website to share their stories.

Archiving stories is a possible goal with the committee forming now, as well, according to Bailey, who said that sharing identities of those on the committee in Colorado will depend on how “protective of their space and their identities” participants want to be. If members want their stories public, she said, the committee may provide a way. “We will be hosting people's bios once we have everybody appointed onto our History Colorado website, so people will be able to see who is on this committee,” she said.

- For the first time, Colorado details dark historical chapter of attempted forced assimilation of Indigenous children in extensive report

- Biden issues formal apology for 150 years of Indian Boarding Schools

- Three survivors of Indian Boarding Schools share the trauma and healing that has shaped their lives