One of the headline bills of Colorado’s 2025 legislative session would rewrite the state’s 80-year-old rule on labor organizing, making it easier for unions to require that all employees at a company pay fees for collective bargaining representation, regardless of whether they are members of the union.

Right now, it takes a simple majority vote for workers to form a union. But achieving so-called union security, where all employees at a company are required to pay for representation, is a much taller task.

The Colorado Labor Peace Act requires a 75% vote of approval before a union can even negotiate with an employer over imposing union security.

Senate Bill 5 would remove the union security vote requirement altogether.

Senate Bill 5 likely has enough Democratic support to pass the state legislature, but Gov. Jared Polis has indicated he won’t sign it into law as is. And the Colorado business community is pushing back on the proposal, too.

Here’s an explanation of the history of the Labor Peace Act, what exactly it does and the political hurdles facing Senate Bill 5 at the Capitol this year.

Colorado labor wars

This is an issue with a long Colorado history in a state that once went to war with itself over labor organizing.

University of Colorado Professor Thomas Andrews directs the school’s Center for the American West. He wrote the book “Killing for Coal: America’s Deadliest Labor War,” which focuses on the epic struggle between the nation's largest union and a coal company under the control of the Rockefeller family.

That conflict included the Ludlow Massacre in 1914 when militias fired on a tent camp in Colorado for striking miners and set it on fire. Twenty-one men, women and children died.

“It's the most famous and most infamous event in a bigger struggle that historians often refer to as the Colorado Coalfield War,” Andrews said. He added that it was national news.

But, according to Andrews, the fighting lasted even longer when strikers responded with a guerilla war in southern Colorado.

“They're pretty successful. They take over company towns, they dynamite coal mines. They pushed back the state militia, and they essentially took control of the strike zone until regular federal troops arrived,” he said.

Andrews said the reaction to all this violence was mixed. Some people backed the strikers, some sided with the company, and a lot of people felt stuck in the middle. But the impacts were felt by everyone. Colorado was a coal state and coal prices went up.

“One of the sort of narratives that really gets increasingly powerful over the course of the strike is this idea that in the struggle between workers and capital, that the general public was being disadvantaged,” he said.

In the following years, Colorado’s politics got more conservative.The state prohibited alcohol in 1916, before it became a national law. Then in the 1930s and 1940s, Andrews said unions were gaining power across the country as part of the New Deal and the passage of the National Labor Relations Act coupled with all the manufacturing during World War II. He said Colorado’s Labor Peace Act became law in 1943 in that bigger context.

“What you see then is that this is in a lot of ways an effort to constrain unions who have become so powerful that they're starting to scare Colorado's powers that be,” Andrews said.

After World War II , Congress passed a law that put new limits on union organizing called the Taft-Hartley Act and opened the door to the kind of right-to-work laws that have spread across the country since then.

In the aftermath, there were a lot of big labor strikes.

“Labor is really militant again, and so the American right tries to push back, and Taft-Hartley gets passed over President Truman's veto and Taft-Hartley then really opens the door for modern to work laws as we know them,” Andrews said.

Those right-to-work laws strip unions of the ability to collect fees from everyone in the workplace as a condition of employment.

How it works

Today the country is almost evenly split between right-to-work-states and non-right-to-work-states.

In non-right-to-work states, if a business unionizes, the union can charge all employees a fee for their representation, even if they don’t want to officially join the union. In right-to-work states, unions don’t have that power — they can still negotiate on behalf of workers, but they can’t actually collect money from everyone they’re representing.

And then there’s Colorado. It’s known as a modified right-to-work state.

That means unions can gain the power to collect fees from everyone in a workplace, but they face more barriers to getting that power than in a non-right-to-work state because of the union security vote requirement under the Labor Peace Act.

Once workers form a union through a simple majority vote, their powers are pretty limited. They can appoint shop stewards and try to get the employer to bargain with them, but they don’t have the resources or power to really fight hard for things like better wages and benefits.

Unions say they need union security fees to fund collective bargaining.

Unions are required to bargain on behalf of all workers at a company, whether they are in the union or not. That’s why they feel it’s only fair that union security be imposed to cover the cost of things like lawyers and negotiating experts.

To be clear, union fees and union dues are two different things.

Workers cannot be forced to join a union, and only members of the union pay dues. That money can go toward things like political activities, whereas representation fees paid through union security can only go toward collective bargaining.

The Colorado Sun analyzed union security votes in Colorado in recent decades, finding they fail nearly half the time. That said, unions have had more success as of late. Of the 25 union security votes taken in Colorado since early 2020, 16 have passed.

The vote can also take some time to happen.

The union security elections are run by the state Department of Labor and sometimes the state isn’t so fast. That can drag out the unionization process, during which the makeup of the workplace can shift and momentum can slow. And employers can do more to pressure workers to change their minds about unionizing.

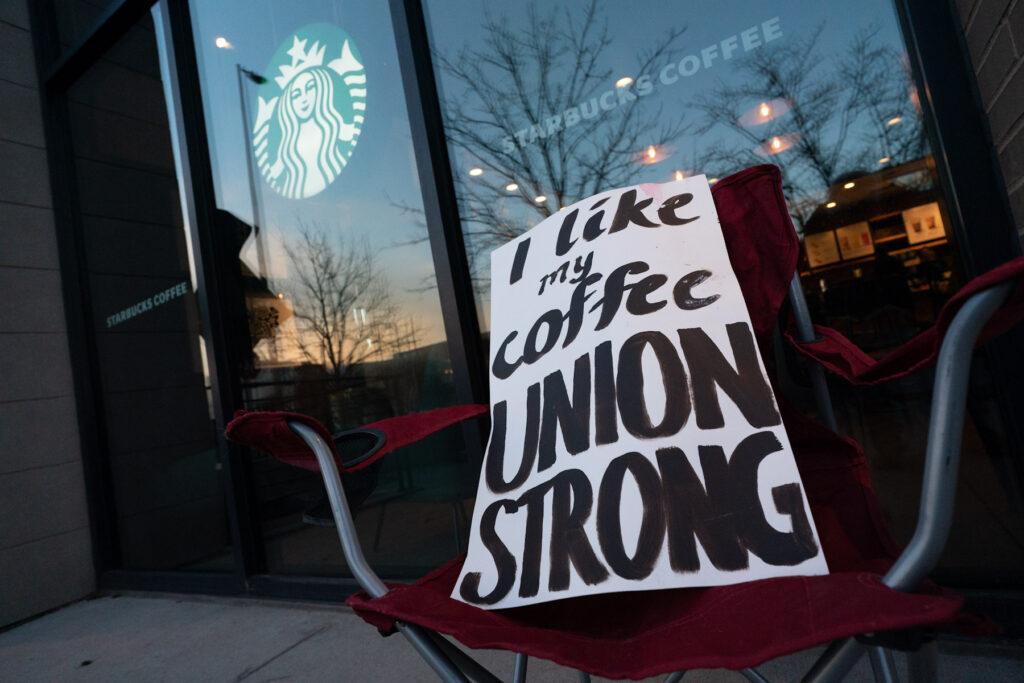

“This is about making sure workers have a voice. It's about ensuring that we have the power to advocate for ourselves. It's about making sure that when we stand together, we can improve our communities,” Liza Nielsen, a former Starbucks worker who tried to unionize her store, testified at the Capitol.

On the other side, you’ve got employers who argue that the threshold for requiring that workers pay representation fees should be high. They are concerned about what it would mean for their ability to hire and the wages they would be forced to dish out if their workers have to pay representation fees.

During the bill's first hearing, business group after business group talked about what a hit removing the union security vote requirement would be to Colorado’s competitiveness. They argue companies would look to right-to-work states when deciding where to relocate.

“We do see this as one more factor that is going to turn folks away,” Loren Furman, who leads the Colorado Chamber of Commerce, told lawmakers during a committee hearing.

Been here before

It’s been awhile since Colorado had a substantial debate over union organizing, but the state has been here before.

In 2007, when Democrats controlled the legislature by narrower margins, they passed a measure similar to Senate Bill 5. But then-Gov. Bill Ritter, a Democrat, vetoed the legislation, describing the debate that session as bitter, partisan and divisive.

In his veto letter, Ritter wrote that he felt the proposal would ultimately hurt Colorado’s economy and make it harder to attract new businesses.

The legislative debate in 2007 touched off a ballot battle.

In 2008, a right-to-work initiative was put on the ballot to restrict union power. In response, labor groups placed two initiatives on the ballot that the business community hated.

The two sides negotiated a deal and labor pulled their measures. In return, the business community joined forces with them to help defeat the right-to-work initiative.

Why this year? And what does the governor say?

This new push to make it easier to fully unionize in Colorado has been building for some time.

About seven years ago, after Democrats won firm control of state government, unions decided to try again, but didn’t move forward because of COVID. The labor movement felt the pandemic was the wrong time to push for such a big change as businesses and workers were dealing with all kinds of other issues.

The political climate for unions has only improved since then. Democrats have even wider legislative majorities. They also have found champions in top leaders like Senate Majority Leader Robert Rodriguez, a Denver Democrat and one of the lead sponsors of the bill, and House Majority Leader Monica Duran, a Wheat Ridge Democrat.

But even with this changing political landscape that’s favorable to union backers, Polis remains the biggest obstacle.

“I'm open to a better compromise than the Labor Peace Act,” said Polis in an interview with The Colorado Sun earlier this month. “(The) Labor Peace Act has certainly served us well, but I'm open to a better compromise if there is one out there. I'm not confident. I don't think there is, but if there is, I'm all ears.”

Polis said Colorado has found this middle ground between those right-to-work and non-right-to-work states and thinks workers need to be able to vote on union security, specifically.

“I'm all for unions and voting by majority to form a union,” he said, “but if dues are going to be deducted from paychecks, I think the workers deserve to have a say.”

He said another potential option is to keep that second union security vote but lower the threshold required for passage. So far, the backers of the measure aren’t entertaining that idea.

Fred Redmond, the national secretary of the AFL-CIO, flew to Colorado to testify at the bill’s first hearing. He said he had an open and honest conversation with the governor, but they just fundamentally have different perspectives on the current Labor Peace Act.

“He expressed to me that he viewed this as a compromise with the business community,” Redmond said. “And I was open and honest with him that we view it as unacceptable. So we'll see where we go.”

This story was produced by the Capitol News Alliance, a collaboration between KUNC News, Colorado Public Radio, Rocky Mountain PBS, and The Colorado Sun, and shared with Rocky Mountain Community Radio and other news organizations across the state. Funding for the Alliance is provided in part by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.