Colorado is known for many things – scenic mountains, evergreens, the outdoors.

Being the home of one of the country’s only Mexican-style bullfights isn’t one of them.

But, it once was. Rumors that one of CPR’s listeners heard are true: a bullfight in Teller County actually happened. It drew a crowd of thousands five years before the turn of the 20th century and resulted in at least one slain bull – a little-known nugget of mile-high lore.

Lisa McKenzie, a professor of environmental epidemiology at Colorado School of Public Health who lives in the Central Park neighborhood of Denver, brought this topic to CPR’s attention. She said in an email: “I am curious to know more about the ghost town of Gillett, Colorado. When I was a child and my family drove by Gillett, Colorado, my mother would say that the only bullfight in the US took place in Gillett. I am wondering how much of the story is true vs myth.”

In a later conversation, she elaborated, explaining that her parents would plan family trips for her and her two younger sisters that often involved camping and swimming in Breckenridge. On the way there, they’d pass through Gillett.

“My mom would say, ‘Look kids, over there is where the only bullfight in the United States took place…’ I think we were kind of interested in it. We’d talk about it a little bit and then kind of move on to other things, but it always stuck in my mind.” She said Gillet, about 10 miles from Cripple Creek “at that time was just a little corral on the side of the road.”

Every Monday CPR presents a story called “Colorado Wonders,” where a question about a Colorado curiosity that a community member brings to the station's attention gets answered by a member of the reporting team, and here’s what some digging into McKenzie’s question turned up.

According to the 2015 online article “A (Mercifully) Brief History of Colorado Bullfighting” in the Denver Public Library Special Collections and Archives, it’s no myth – a pricey multi-day bullfight happened 130 years ago in what is now the “present-day ghost town” of Gillett, during which one or two of the five participating bulls were killed.

“Gillett, Colorado was a small mining town in Teller County, CO. In 1895, it was the site of the only bullfight in the continental United States, drawing 50,000 spectators ... In the early 1900s, Gillett disintegrated and became one of Colorado’s present-day ghost towns,” the report states.

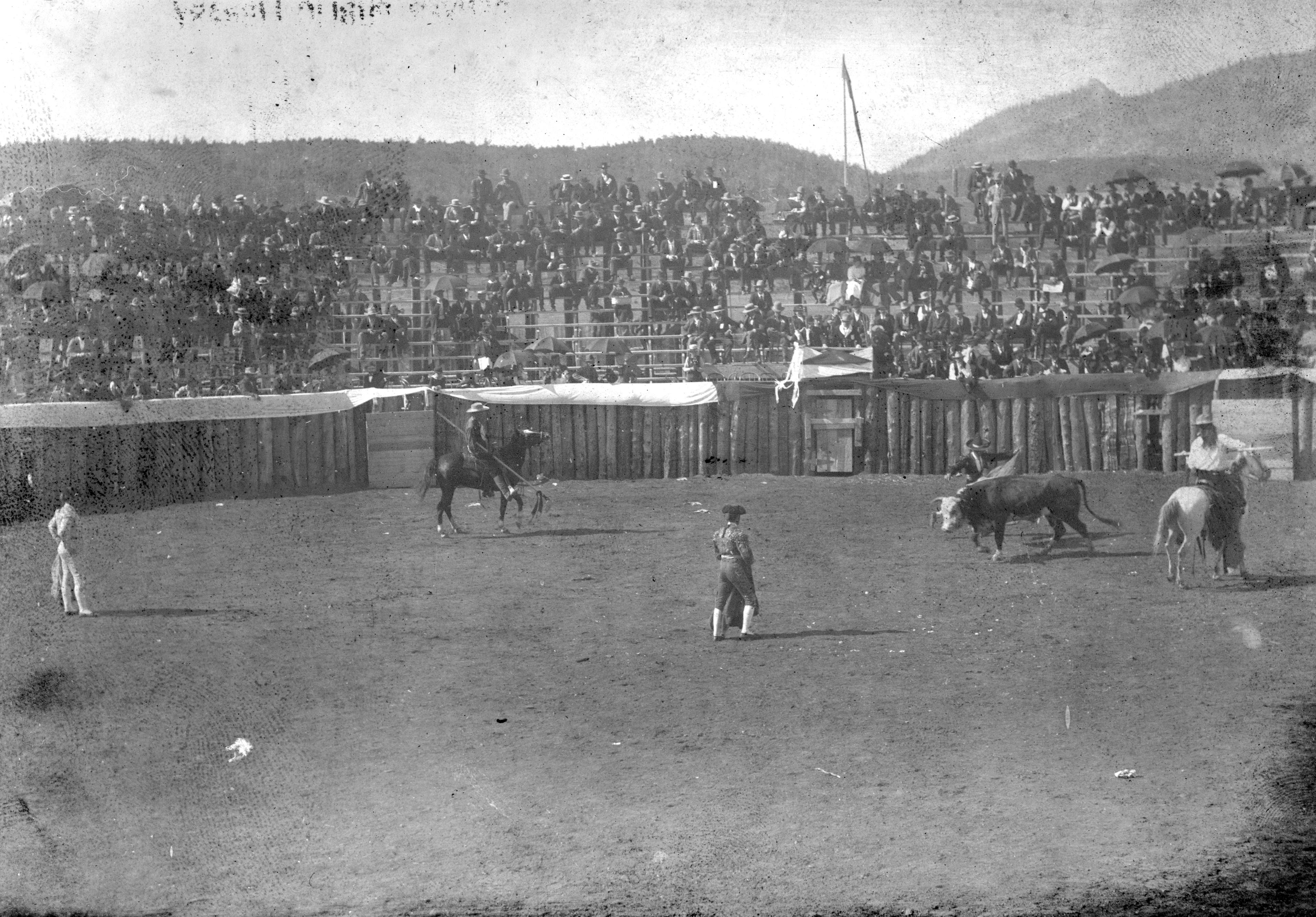

Other publications say the crowd was closer to 5,000, not 50,000, which seems more likely from the photos in the Denver Public Library archive, which described it as the second Mexican-style bullfight in the US, without indicating the location of the first. Mexican-style bullfighting tends to involve the use of swords and spears by matadors against the bulls, with the end goal being killing the bull.

So how’d this event find its way onto a track and into Colorado history? Several sources – newspaper articles, library archives, and a local historian – helped fill in the blanks. Although some account details differ, all would agree that the event was a failure.

It didn’t start out that way, though. The bullfight idea was sparked when a casino owner named Joe Wolfe wanted to put Gillett, a speck of a town, on the map. He thought hosting a bullfight there would do it.

Gillett, whose population peaked at 1,500, was about 10 miles from Cripple Creek, a city known for gold mining, located about 115 miles south, and slightly west, of Denver.

“Wolfe hoped that staging a large event would elevate Gillett's fortunes and secure it a spot as the county seat of Teller County,” according to the archived article. “He was so confident that he sunk a great deal of cash into importing four bullfighters from Mexico and constructing an elaborate bullfighting arena capable of seating thousands of spectators.”

In addition to imported bullfighters, the five bulls involved in the event were also imported from Mexico, according to David Martinek, a retired Realtor who moved from Kansas to Teller County nearly 20 years ago and has since immersed himself in county history. He now holds the title of chairman of the Teller County Historic Preservation Advisory Board.

He said a possible reason for holding the bullfight there was that Gillett was founded earlier the same year, and the fight was “some sources say to commemorate the founding of Gillett,” he said in an interview from his home in Divide, a town in Teller County.

The event was set to last three days, starting August 24, 1895 – but it never made it to August 26, 1895, as planned.

Right away there were problems, one of which was the welfare of bulls. Accounts vary as to where they came from. The archived article explains the bulls were farm-dwellers unfamiliar with fighting.

“Unfortunately for everyone involved, especially the animals, the bulls chosen for the fights were not the sorts of bulls you'd normally find in a bullfighting ring south of the border,” the library report states. “These sad animals were common farm animals and were in no way prepared to participate in bloodsports of any kind.”

But Martinek has a different version: the bulls, he said, came from Mexico, and were unprepared for different reasons. The US Department of Agriculture had recently approved importing cattle from Mexico, he explained. “So they figured that well, if we can import cattle from Mexico to eat, then we can import bulls from Mexico to have a Wild West show. And they proposed this in July of 1895. And so they ordered five bulls from Chihuahua, Mexico and a famous bullfighter and his wife. They came up in late August by rail.” It’s unclear who, if any, the other bullfighters were.

Once they experienced Colorado’s elevation, the bulls, who may also have been deprived of hay, couldn’t handle it.

“Bulls were not used to the altitude and they hadn’t been fed, and so they may have been weak, and so it was all kind of a disaster in many ways,” Martinek said.

Before the fight began, some people found the idea of bulls fighting for sport unacceptable, since they would be speared during the event.

“These folks took their concerns to the state Capitol in Denver where they found a sympathetic ear in Governor Albert W. McIntire. McIntire immediately dispatched the State Humane Officer to confirm that a bullfight was really going to take place,” according to the library’s report.

Those organizing the fight had prepared for opposition, and paid fines for cruelty to animals ahead of time to allow the fight to go on, the library article states.

Tickets to the bullfight weren’t cheap. They cost $5, according to an audio story as part of an “Archives on the Air” series published by Wyoming Public Media. That would equal about $190 today.

Accounts vary as to how many people showed up. Linked to the Wyoming Public Media story is an article from an unidentified newspaper with the headline: “Big Bullfight Bought Fame to Gillett,” which is now part of the Benjamin F. Davis Papers, archived at the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming.

The article states of the bullfight: “A grandstand and bullring had been built at the race track and 5,000 people came to see the gaudy show. The Denver News reported that every horse and every rig in the Cripple Creek district was headed toward Gillett on that day.”

Martinek estimates the attendance as even less than that – “I’ve read books that said maybe 3,000 people attend on a Saturday,” he said – but he added there’s no official head count.

Once the fighting began, the bulls were stabbed and suffered – and that article states that two of them died painful deaths. Although Martinek had learned it was just one bull who died, that their deaths were not quick or easy is uncontested:

“... they were not versed in the elaborate rituals used to hasten an animal's death in the ring,” according to the library’s story. “Suffice to say, the one bull that was actually killed that day (and the bull killed the next day) suffered tremendously.”

That’s what caused what was set to be a three-day event to get truncated to two: “Though several thousand spectators showed up the second day, the bulls' lack of enthusiasm endeared them to the crowd, and the fights were stopped after a single death. The third day of bullfights was canceled entirely,” the library article reports.

There’s no disagreement about the event being a flop. The newspaper clipping said it “turned into a fizzle ... and bullfighting in Colorado came to an abrupt end.” Or, as Martinek put it: “It was pretty much an event that didn’t go well.”

And it was not without consequences.

“Both of [the organizers] and all the people that came up from Chihuahua were arrested ... for animal cruelty,” Martinek said. He added that some were also fined $60 – about $2,200 in today’s money – “which they paid and got on the next train and went back to Chihuahua.”

It’s unclear what became of the bulls who survived. Meanwhile, Wolfe, the guy who came up with the idea, high-tailed it out of Colorado to Oklahoma and was never seen again, Martinek said.

The story of the bullfight from more than a century ago, featuring non-fighting bulls and inexperienced and/or imported bullfighters in a community whose population is now recorded as “none” did not match with the findings imagined by Lisa McKenzie, the Denver professor who first asked about it.

She was reached over Google Meet and presented with the detailed answer to the question of whether the bullfight-in-Gillett story was fact or myth, she said she had envisioned a much more innocent event when her mother mentioned it.

“I’m thinking, ‘Those poor bulls,’’ she said. “I was a kid, so I just thought of a bullfight … in the cartoons with the matador and the bull running around the area ... the ‘Bugs Bunny’ cartoon with Bugs Bunny being the matador, is kind of what I thought when I was a kid. I was a child in the ‘60s, so it was entirely different times.”

Today, there is bullfighting in Colorado – but not the kind that involves causing harm to the bulls, according to Ryder Rich, a professional bullfighter from a Northern Colorado bull-fighting family who co-owns American Bullfighting. A self-described “aficionado in the bullfights,” he owns 80 head of Mexican fighting bulls and performs about 100 times a year.

Reached for a Google meet from outside the ring he runs in Eaton, he was surprised to learn of the Mexican-style bullfight of 130 years ago. “As much as I qualify myself as an expert, that’s a new one for me,” said Rich.

He took a look at some of the library research about the bullfight and said it’s nothing like the sport he’s a part of: today’s bullfighting matches are about 60 seconds long, and would not involve non-athletic, climate-unready bulls, and certainly no cruelty to them. “We can’t do that here. Even if we wanted to go do a same-type bullfight where they use swords and everything like that, that’s outlawed now.”

He was clearly uncomfortable to hear the animals he reveres had suffered. “Back then, if they brought these guys in from Mexico and everything, I would have to assume that they were doing some kind of event where they were using their swords and stuff like that, which was tradition for them ... if they were dying, I would have to assume that they were getting stabbed.”

He said in American bullfighting as he knows it, his bulls only compete about six days a year, and the fights don’t involve any weapons. Instead, “We get dressed up as rodeo clowns … we go out there and we got our face painted. We got the goofy-looking baggy shorts on.”

Then it’s man vs. bull, not man with sword vs. bull, he said. “We only go out there jiving around them. If there’s any bloodshed, it’s on our end.”

The bulls are treated with reverence. “I mean, we have a full lineage book of where these animals come from, how they’re bred, what this one needs,” he said.

The risk of harm is to the bullfighter in the baggy shorts, not the bull, he said. “This is a game you’re playing with fire – you’re going to get hit at some point. You just hope that you can get up and get through it and make it to the next day.”

McKenzie, the Denver professor who brought up the topic, would agree with Rich that the bulls got a raw deal. “Well, now I know what really happened ... Knowing the full story, it’s really poignant how gruesome it can be,” she said of Mexican-style bullfighting that occurred in Gillett.

“As an adult, I know more of what bullfighting is and that it’s not done as much because of the cruelty to the animal involved.” And, of the mythical bullfight she heard about from her mother when she and the rest of the family headed to Breckenridge for outdoor adventures, she concluded: “I guess I’m happy to hear that it didn’t continue.”