This story is part of The Trip, a CPR News series on Colorado’s new psychedelic movement.

Early research indicates that the psilocybin found in psychedelic mushrooms could be beneficial in treating mental-health conditions such as PTSD, anxiety, addiction and perhaps even previous traumas such as abuse or assault.

But how does it work? To put it simply, it’s still too early to tell but scientists in labs around the world are attempting to find out.

Dr. Scott Thompson is a neuroscientist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. He’s studied psilocybin and is currently part of the research team led by Dr. Andrew Novick., an MD in the Department of Psychiatry at CU Anschutz, looking into how psilocybin-assisted therapy could help people with treatment-resistant depression.

What does psilocybin do? What is the experience like?

When psilocybin is taken in large or full doses, patients consistently describe a series of psychedelic experiences such as the dissolution of the ego, oceanic boundlessness, the suspension of time as well as auditory and visual hallucination.

- The dissolution of ego — sometimes referred to as “ego death” — is where a person’s self identity disappears. Patients report experiencing a perspective shift with their lives as well as a more connectedness with the world. “The border between you and the rest of the world dissolves a little bit and you begin to feel like you are more a part of nature and the universe,” Thompson said.

- Oceanic boundlessness is a term for a general feeling of limitlessness, a feeling of consciousness that goes beyond the physical body, according to the American Psychological Association.

- Suspension of time is an experience of relativity, where time seems to move very slowly or not at all, even though thoughts and feels continue unabated.

- Auditory and visual hallucinations can start out as vibrations or saturations of color, but can go much further depending on the patient.

It’s currently believed that these psychedelic experiences could be necessary for potential therapeutic benefits, but more research needs to be done.

What does psilocybin do to the brain?

There’s still a lot we don’t know about the biological effects of psilocybin and other psychedelics. The current established thinking is that psilocybin disrupts and promotes connections between brain cells.

“In a general sense, the term that we've all settled on for the moment is they promote something called neuroplasticity,” Thompson said. “Neuroplasticity is a capacity of every brain — every animal's brain, certainly the human brain is very good at it. Every time you learn something new, your brain is experiencing neuroplasticity.”

“This is not something that is incredibly foreign to brains, but for reasons that remain not completely understood, it seems that psychedelics have the ability to promote this process.”

Thus far, researchers believe this type of neuroplasticity pairs well with therapy.

“When you are in a state of heightened neuroplasticity and you are faced with something challenging from your past, it gives you the opportunity to essentially reset the way your brain responds to things that might be triggering,” Thompson said. “You learn, through neuroplasticity, a new way to confront those triggering events that may be holding you back in life.”

I’ve heard of a “Bad Trip.” What is that?

Some people have reported extremely unpleasant experiences when taking psychedelics, describing nightmare-like visions, feelings, and journeys. These are often referred to as “bad trips.”

Thompson says part of his research and the intentions behind best practices created by the state are meant to mitigate negative outcomes such as “bad trips.” Advocates often call this “set and setting,” referring to the importance of the physical space around a patient as well as the mental or emotional mindset and intention a patient has going into any psychedelic dose. In Colorado, the state requires patients to have at least one preparation session before the admistering of psilocybin and one integration session after.

“It's been found through experience over the last decade or so that if you prepare people, make sure they know what they're about to experience, then you can help them to avoid having what used to be called a ‘bad trip,’” Thompson said. “We help them to prepare for their intentions, what do they hope to get out of this, and we just let them know what the experience is going to be like. And again, that has proven over the years to minimize the risks of people having a really bad experience.”

Thompson also differentiates between negative experiences and challenging experiences.

“If you've got some traumatic event in your childhood, staring that face-to-face can be very difficult,” he said. “Again, the experience over the years has suggested that the challenge of facing these moments from your life leads to the benefits afterwards. And so I want to point out the boundary between a challenging experience facing a trauma and a ‘bad trip’ where it's just not doing you any good at all. In fact, it could be damaging.”

Do people who’ve lost loved ones really experience encounters with them?

Every person’s experience with any psychedelic is different. Some people have reported conversations with people they’ve lost or returning to certain past experiences.

“These medications seem to have the ability to allow you to face challenging experiences that you've had earlier in your life,” Thompson said. “And those can seem very realistic. You may feel like you are having an encounter that you're reliving some conversation that you had or some event that occurred earlier in your life. That is presumed to be part of the healing process.”

Thompson says these types of psychedelic experiences appear to be beneficial in treating past traumas, but he emphasized the need to have proper scaffolding and support — such as preparation sessions before taking the drug and experienced facilitators.

“Part of what makes you feel better on the other side is your ability to confront something that you may have been avoiding. But it can be very challenging for the patients.”

What do we know about the safety of psilocybin?

There is still a lot to be learned about the biology of psychedelics, particularly long-term effects.

However, one known red flag is any family history of psychosis or schizophrenia.

“We know that psychedelic use is very strongly correlated with a first episode psychosis in some people and we also know that psychosis runs in families,” Thompson said. “One of the things that's absolutely essential for anybody thinking of trying psychedelic medicines is to ask your doctor if psilocybin is right for you. Talk to somebody about your family history.”

Healing centers and facilitators will be required to ask patients about family and medical history before proceeding with psychedelic-assisted therapy.

How does psilocybin interact with medications like antidepressants?

Thompson said it’s important for a facilitator to know if a patient has used certain medications, such as an SSRI (a common antidepressant) long term. It’s currently believed that SSRI’s can change the way someone responds to psychedelics such as psilocybin.

“Psychedelics act through the serotonin receptors, and so if chronic use of SSRIs has caused a number of receptors to go down, there are fewer things for the psychedelics to interact with,” he said. “And so, for a given dose of psychedelics you would expect a smaller response. The jury is still a little bit out on that.”

The concern with mixing SSRIs and psychedelics is not about negative results, but potentially reduced affectiveness.

“It's really well established at this point that the intensity of the psychedelic response — that mind altering behavior that you feel when you're under the influence of psychedelics — correlates with the therapeutic benefits,” Thompson said. “Is it necessary to have a very strong psychedelic response in order to have a therapeutic benefit? Or would a milder response — if the serotonin receptors have been downregulated by SSRI use —- still be able to produce a therapeutic benefit afterwards? We need more studies.”

What kind of research is being done to study psilocybin?

There are decades of research around psilocybin. However, human studies and clinical trials are only beginning to take place and we likely won’t see results for another couple of years.

“These are still early days and I can't say that enough,” Thompson repeated to Colorado Matters. “There's a great deal of work going on in my lab and dozens of labs around the world to better understand the biological underpinnings of this potential therapeutic response.”

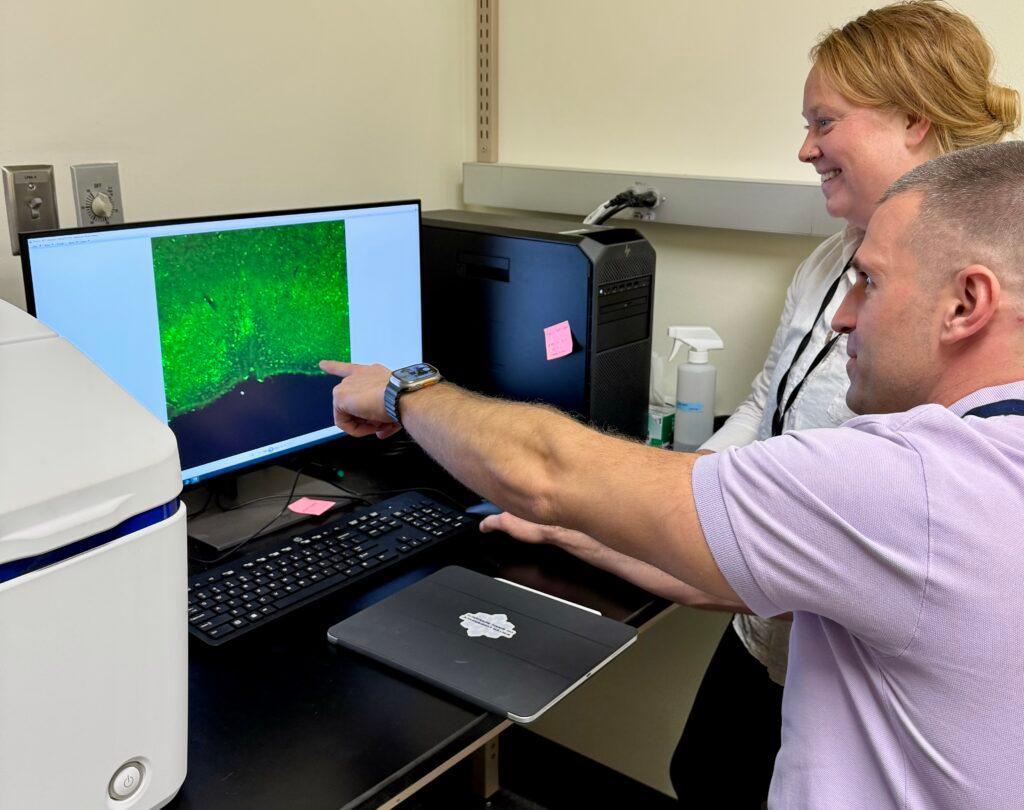

Drs. Jillian King and Devin Effinger, researchers in Dr. Thompson's lab, examining biomarkers of neural activation within brain tissue following administration of a psychedelic to better understand how these drugs alter baseline activation within specific brain regions.

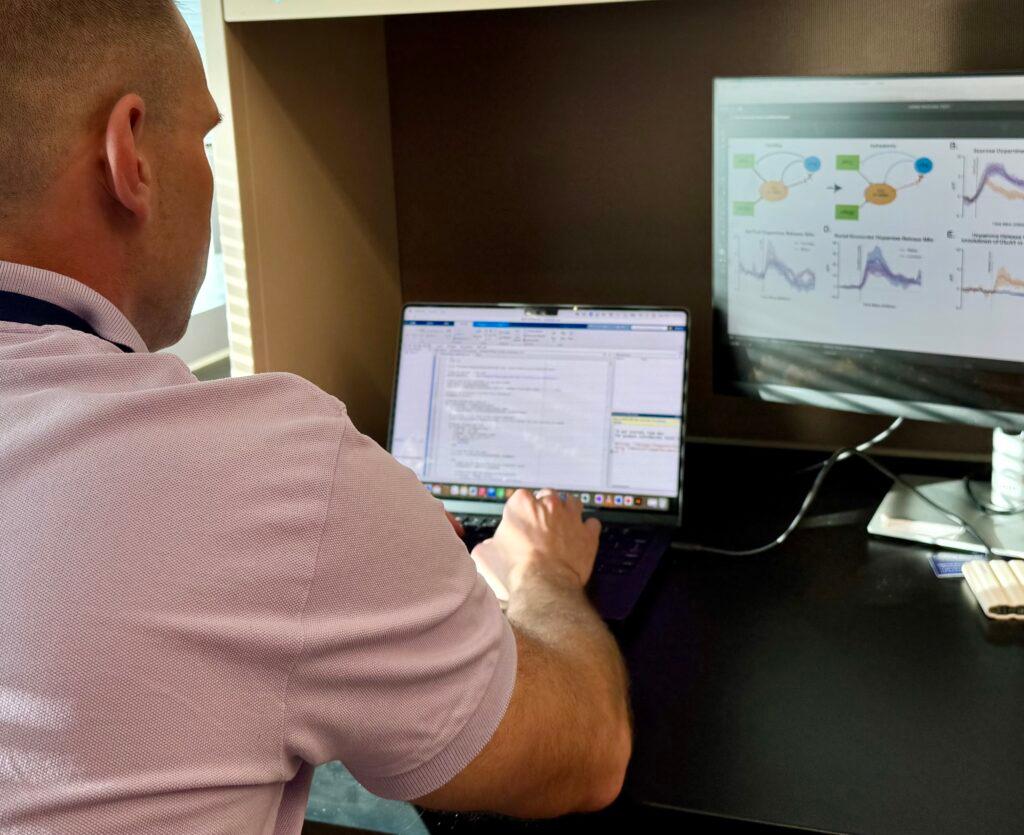

Dr. Devin Effinger, a researcher in Dr. Thompson's lab, writing custom code to analyze data from experiments wherein he measured real time release of dopamine in response to various stimuli following administration of a psychedelic.

Thompson is currently part of a study at CU Anschutz looking at how psilocybin can assist with treatment-resistant depression. Previous research has shown that psychedelics are at their most beneficial when coupled with therapy. However, in this CU study, Thompson, Dr. Novick and their colleagues have minimized the amount of therapy involved in order to study the effects of psilocybin doses on the trial participants, which focuses on a symptom of depression called anhedonia.

“Anhedonia is the symptom in which the patients fail to feel pleasure for stimuli and events that should be rewarding,” Thompson said. “A good book, a good meal, a good movie, time spent with loved ones, time spent with your children, all these things. If you are suffering from depression with anhedonia, those things are no longer pleasurable.”

In this study, patients have been asked to ween themselves off any other antidepressant medications. They go through the three step process now mandated by the state — a preparation session, an administration session where they are given a full dose, and an integration session. (That process was modeled from established academic processes, according to Thompson, who advised the state.) Patients will be given one full dose, which will likely induce an intense psychedelic response. Researchers will study the patients’ behaviors, responses as well as brain scans.

Here's more information about the study on depression, including criteria for people interested in participating. Results for the study are expected in two years.

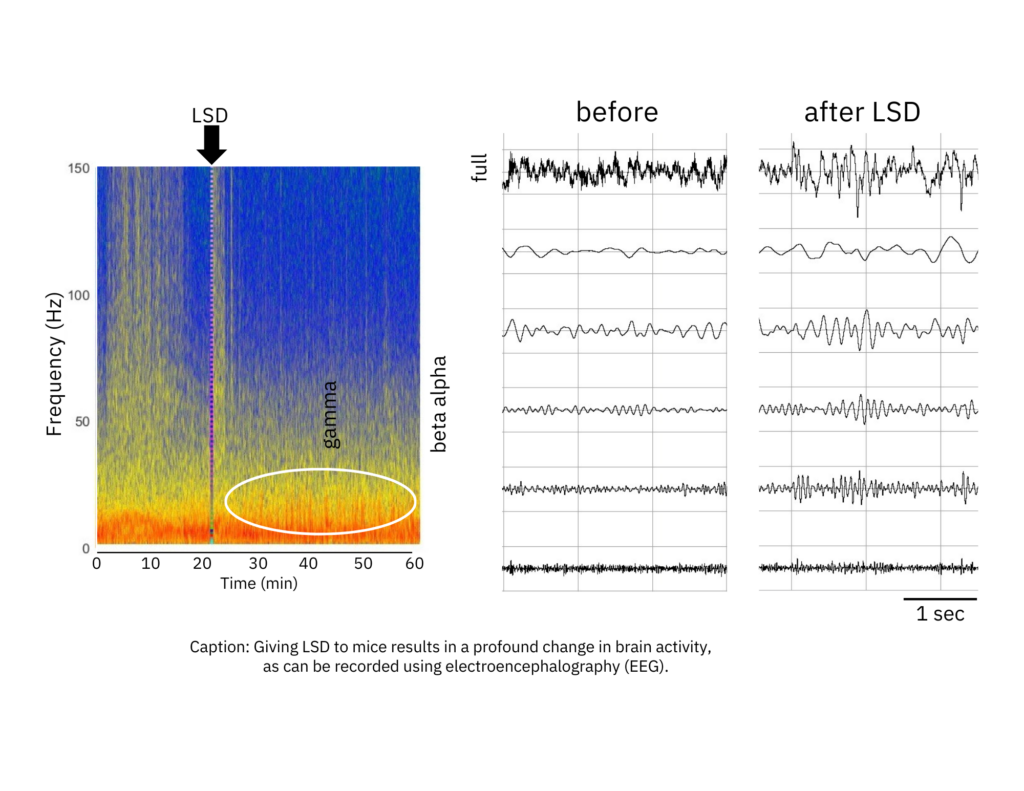

Thompson has previously tested the effects of psilocybin and LSD on mice.

“Mice that are displaying this anhedonia behavior don't respond in a normal way to rewarding stimulus, like a sucrose solution,” he said. “And so if you give them psychedelics, their behavior, their ability and desire to drink a sucrose solution goes up within 24 hours, that's an anti-anhedonia response. That's the kind of thing that we would like to be able to reliably produce in a patient with treatment-resistant depression.”

Afterwards researchers also scanned the brains of the mice and saw increased connections between cells.

“What we see is that they are stronger,” he said. “So the brain change goes hand in hand with the behavior change.”

Thompson says the next step is to verify if the same results are produced in the human clinical trials.

The Trip: Alejandro A. Alonso Galva is the project editor. Carl Bilek is the executive producer for Colorado Matters. Andrea Dukakis is a reporter/producer/host for Colorado Matters. Megan Verlee provided editorial guidance. Lauren Antonoff Hart is the digital producer.

Editor's note: This story has been updated to fix a misspelled name.