Updated Feb. 20, 2025 at 9:10 a.m.

Republicans in Congress are pursuing up to $4.5 trillion in tax cuts, as part of a budget blueprint that aims to also cut spending and direct funds to border enforcement.

As part of the plan, they’re looking to sharply scale back Medicaid. That’s the complex $880 billion-a-year state-federal program, which offers health coverage to millions of low-income and disabled Americans. About a quarter of Coloradans rely on the state’s Medicaid program for coverage.

“I need help. I need taxpayer help. And it's very humbling,” said Veronica Montoya, a Medicaid recipient in Denver, of the cuts that could upend her life.

“Medicaid is hugely important for so many people. And I am just an example of somebody who can go from making six figures to making nothing. And I need help because of the health issues,” said Montoya, a licensed real estate broker, whose career has been severely hit by a cascade of autoimmune problems, combined with other conditions like diabetes.

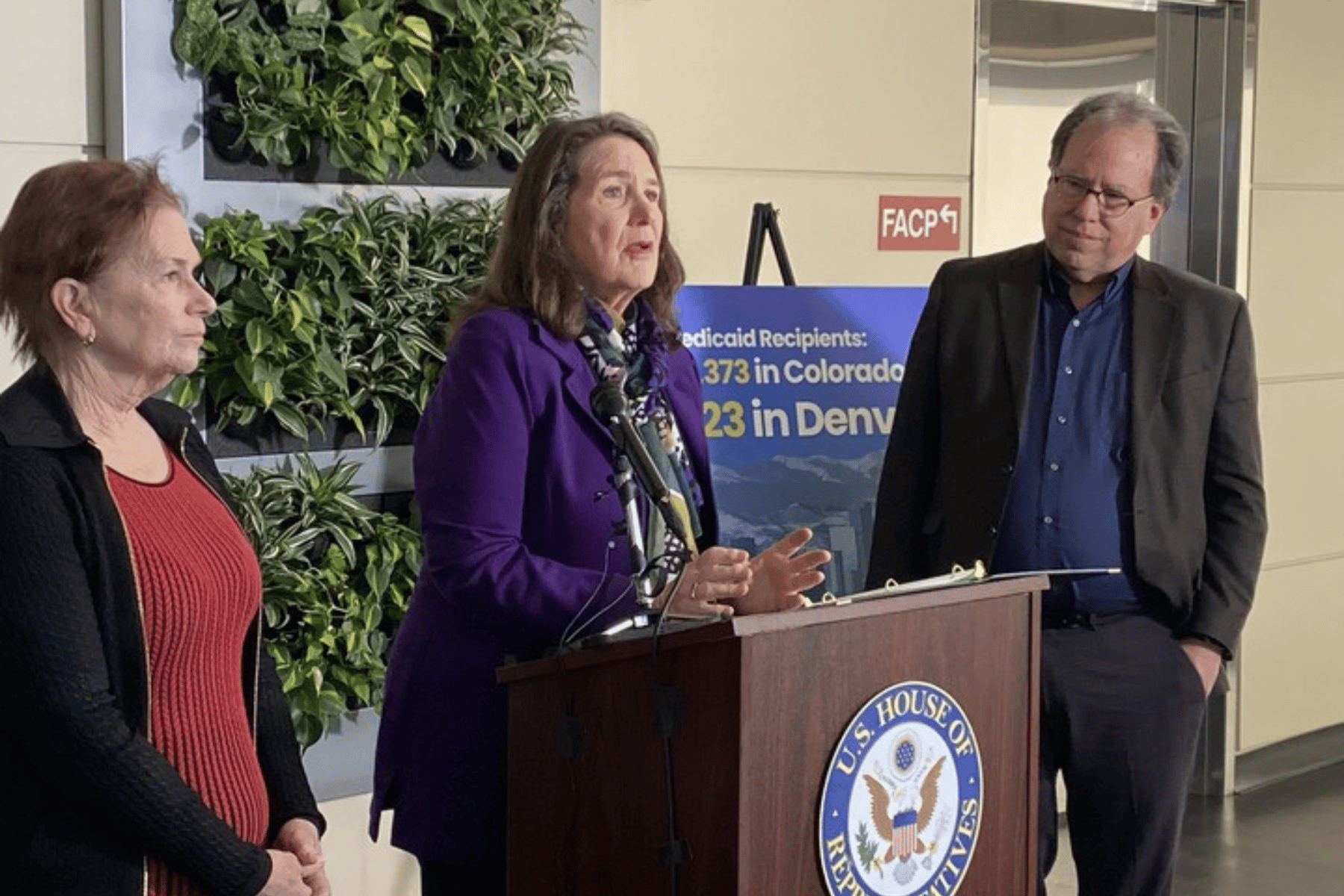

Health leaders warned of potentially devastating impacts of deep cuts at a press event Wednesday in Denver. Those include Coloradans losing access to health care; hospitals, especially in rural areas, clinics and community health centers closing; and increased costs across the health system, including for people who aren’t enrolled in Medicaid.

“It is the shredding of the social safety net,” said Rep. Diana DeGette, a Democrat whose district is based in Denver. She said traditionally Medicaid was for poor people, seniors who needed long-term care and maybe some children. “Now, a huge percentage of Americans use some form of Medicaid to help pay for their health care costs. So you're talking about a shredding of the health care system that impacts all Americans.”

About half of Coloradans get insurance through an employer, but a large share, about a fifth of the state population, are enrolled in Health First Colorado, the state’s Medicaid program. That’s more than a million people, 1,212,424 to be exact, according to Colorado’s Department of Healthcare Policy and Financing.

Deep cuts to Medicaid would be keenly felt at hospitals, which both provide health care to many Medicaid patients, but also rely on reimbursements from Medicaid from the federal and/or state governments to pay for that care.

For Denver Health alone, the state’s flagship safety net institution, major cuts could cost close to a billion dollars out of its $1.5 billion budget.

“We can't afford to do that. We'd have to cut services, we'd have to lay off employees,” said Donna Lynne, its CEO. “The impact not just in Denver, but in the entire state is catastrophic.”

Many hospitals, especially in rural Colorado, have extremely narrow profit margins.

“Medicaid cuts of any kind, and especially those that would be as significant as the ones we're hearing about in Congress, would be devastating not just to patients, but also to the people who deliver their care,” said Jeff Tieman, president and CEO of the Colorado Hospital Association.

He said it would mean that people lose coverage and access, the hospitals would have to close down services, some hospitals would close and medical staff would be laid off.

“We cannot afford that. We can't afford it right now. We can't afford it ever,” Tieman said “Medicaid is a lifeline and it is crucial to the success, frankly, of our entire state.”

The leader of a nonprofit community health center described the risk of possible cuts as profound.

“If our Medicaid revenue was cut, say by 50 percent, we would experience a little over a million dollar reduction to our roughly $11 million budget,” said Jim Garcia, CEO of Tepeyac Community Health Center, a nonprofit community health center in Denver. “This would be a devastating impact on our already lien budget and would require us to contract our services and limit the care we're able to provide to our patients.”

More importantly, he said, would be the human toll. Patients who can’t go to a clinic like Tepeyac will delay or forgo health care altogether.

Research backs up this idea that when people lose health insurance, they are more likely to delay or go without necessary healthcare. That is because of both cost and lack of regular healthcare. The result can be worse health outcomes.

Many of them, history has shown, when their health deteriorates, end up in emergency rooms, driving up costs for hospitals.

“Bottom line is that we need to work together to preserve this lifesaving investment that Medicaid represents to our communities. It is an investment of health well-being in the future of communities throughout Colorado,” Garcia said.

The American public holds favorable views of Medicaid, according to independent poll

Behind the speakers as they talked with journalists was a pair of posters. One was entitled: Medicaid Recipients, with numbers: more than a million in Colorado, more than 100,000 in Denver.

Another cited a poll on Medicaid showing broad support of all Americans, and not just Democrats and independents as some might think, who pay for the program through their taxes.

Most Americans, a full two-thirds, have some connection to Medicaid, through health insurance, pregnancy-related care, home health, nursing home care, coverage for a child or to help pay for Medicare premiums, according to recent polling by KFF, an independent source for health policy research, polling and news.

Large majorities view it favorably, including 64 percent of Republicans, 81 percent of independents and 88 percent of Democrats.

The polling also showed most Americans think Medicaid works well for lower-income people, though there is a partisan divide over whether Americans see it mostly as health insurance or a government welfare program. Most Democrats and independents say it is mostly a health insurance program, a small majority of Republicans view it primarily as a welfare program, according to the poll.

In recent years, Medicaid coverage has expanded in many states under the Affordable Care Act, often ones led by Republicans, to cover more low-income adults. The KFF poll found two-thirds of people living in non-expansion states want their state to expand their Medicaid programs.

The story of one Coloradan

Medicaid has been nothing short of a lifesaver for Denverite Veronica Montoya, a licensed real estate broker.

“Oh my gosh, completely,” said Montoya, who attended the news conference.

She first got sick in 2005 and a decade later was diagnosed with a series of health conditions, mostly autoimmune diseases, including lupus and something called ankylosing spondylitis, a chronic inflammatory disease that primarily affects the spine, plus diabetes, osteoarthritis, and long Covid.

“There's just a lot of autoimmune stuff going on,” she said. “So I am the poster child for invisible disease because as you can see, I don't look sick or how you imagine a sick person to look, but I live in a pain body.”

She said she was in varying degrees of pain every day, including in her neck and head, nerve pain and chronic migraines.

She takes medication that makes it bearable. “Prior to being on that medicine, I had no movement in my spine. It causes inflammation of the joints of the spine. So I had no movement in my spine. I basically went from bed to couch every day,” Montoya said.

The Medicaid program pays for her medicine, so for her to lose her Medicaid coverage would be life-altering. “As it stands now if I lost Medicaid, I just don't know how I would pay for the medicine. It's $15,000 a month,” she said.

Medicaid has long drawn the ire, even scorn, of many conservatives and Republicans, who think it’s too expensive and inefficient and that the program should be smaller.

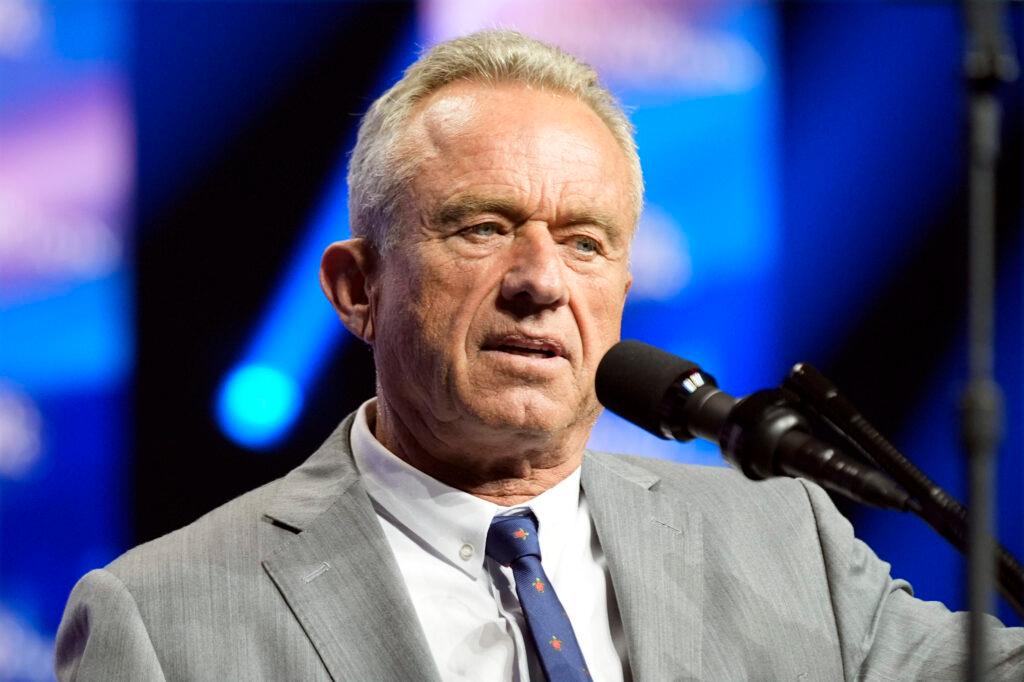

Robert F. Kenney Jr., the new Secretary of Health and Human Services, voiced some of those concerns at his confirmation hearings. "Medicaid is not working for Americans," said Kennedy, who said though hundreds of billions of dollars are being spent on the program, the population gets sicker each year. At other points in the hearing, he struggled to answer basic questions about the program.

But Montaya said she thought Americans and Coloradans are starting to wake up and will speak out about the looming cuts, as they start to understand potential impacts on their own lives and those of family, friends and neighbors.

“I really do. I mean, especially when you start seeing the rural hospitals closing,” she said. “Those are a lot of the constituents typically of more conservative representatives. And when they start losing their health services, then I think more people will wake up. But I do think a lot of people are becoming more aware of the need for safety nets like Medicaid.”

Editor's note: This article was updated to reflect the number of people taken off coverage during the Medicaid Unwind. About a fifth of the state's population are enrolled in Health First Colorado, the state's Medicaid program.