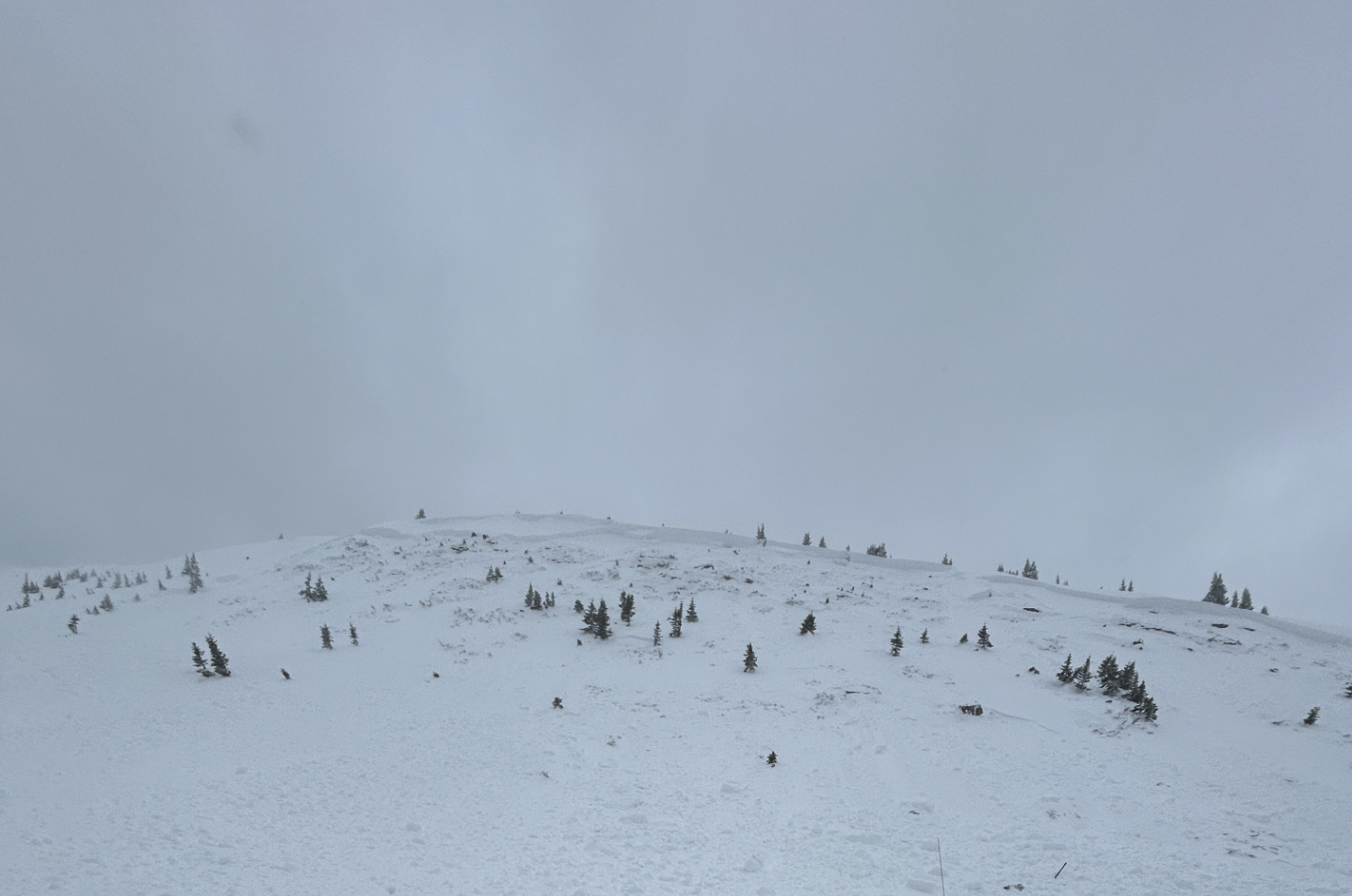

When someone is buried in an avalanche, the difference between life and death can be a matter of minutes. On President’s Day, a snowmobiler survived for an hour under the snow of an avalanche he triggered.

The Colorado Avalanche Information Center said the man was completely buried by the avalanche near Vail Pass on Feb. 17. After a friend was unable to find him with an avalanche beacon, he called 911. The rescue team spotted a small bit of this orange avalanche airbag sticking out of the snow once they arrived. Beneath, they found the missingman, who was cold but talking.

It’s “highly unusual” for someone to survive so long under the snow, said the information center’s director, Ethan Greene.

“And so that is very lucky for all of us that these guys get to go home to their families, and we don't have that wake of grief and pain that ripples through their communities,” he said.

In most cases, Greene explained, by the time a search-and-rescue team has arrived at an avalanche, the incident has become a recovery mission. He can’t exactly say what saved this man but guesses it was a combination of factors, including the fact he was wearing an avalanche airbag, sort of like a balloon in a backpack, which may have helped keep him closer to the surface and could have created an air pocket. The victim’s helmet and face mask may also have helped create that breathing room.

Much of what saved him, however, may have just been luck. About a third of people who die in avalanches sustain blunt force trauma from hitting a tree or rock, Greene said. The other common death is asphyxia, even though there actually is quite a lot of oxygen in the snow.

“So it's not so much that you can't get oxygen,” Greene said, “It's that you can't get the CO2 away from your airway.”

Body camera footage from the Summit County Sheriff’s Office points to another factor: the fluffiness of the snow. Avalanche survivors often talk about being stuck in snow that feels like concrete, but the body cam shows the rescue team digging through pillowy powder that gave way easily as they uncovered the man, buried approximately 2 feet below the surface.

Greene cautions that backcountry users should not expect to get this lucky. Even with appropriate avalanche training and gear — including a probe, beacon, shovel and airbag — it’s impossible to predict whether someone will be able to create a crucial air pocket if lost in an avalanche.

“It just goes back to that old adage: The best thing that you can do to try to survive an avalanche is not get caught in one in the first place,” Greene said.

Checking the avalanche forecast is crucial, he went on, both when you’re making your plans and again right before you head out into the backcountry.

While this winter’s death toll from avalanches has been relatively low, with only one fatality so far, Greene stressed that February and March are typically the deadliest in Colorado.

“We have a lot of winter left,” he said.