Updated March 6, 2025, at 9:35 a.m.

It’s November 2021 and at Ascension Catholic Parish in Denver’s Montbello neighborhood, everyone wears a mask. A woman with long dark hair is at the pulpit. She introduces herself.

“Buenos días, mi nombre es Julissa Soto.”

She’s here to tell the congregation COVID-19 vaccines are safe, effective and available. Soto is a health equity consultant. “I'm on a mission to get my community vaccinated, and I will not stop until I get the last Latino vaccinated,” she told CPR News that day.

Over the course of the pandemic, she did indeed help get a lot of people vaccinated — at more than 400 vaccine clinics and events like the one at that church.

Fast forward to 2025, and Soto says it’s important to remember the losses. “Really sad, lots and lots of people died,” she said in an interview.

In Colorado, the number of people who died surpassed 16,000 people, according to figures posted by the CDC. Most Coloradans got vaccinated, but the Latino community, which has been hit hard by the virus, barely got to 50 percent, she said. For Soto, it was “an opportunity to highlight the inequities. They have always existed in public health.”

But the pandemic put the reality in people’s faces. She used that message to help, by her count, 60,000 people get their shots. “I believe that we're going to find solutions,” Soto said.

Among the lessons Julissa Soto says she learned: to pivot, think on your feet, remove barriers, challenge the status quo. “Remember from every setback, it will be a comeback.”

And a half-a-decade later, that’s one thing I found out talking to people from around Colorado. The pandemic has been rough — challenging and tragic — it was also an opportunity, and some major changes in everyday life turned out to have bright sides.

“If you can't take care of yourself, how are you going to take care of other people?”

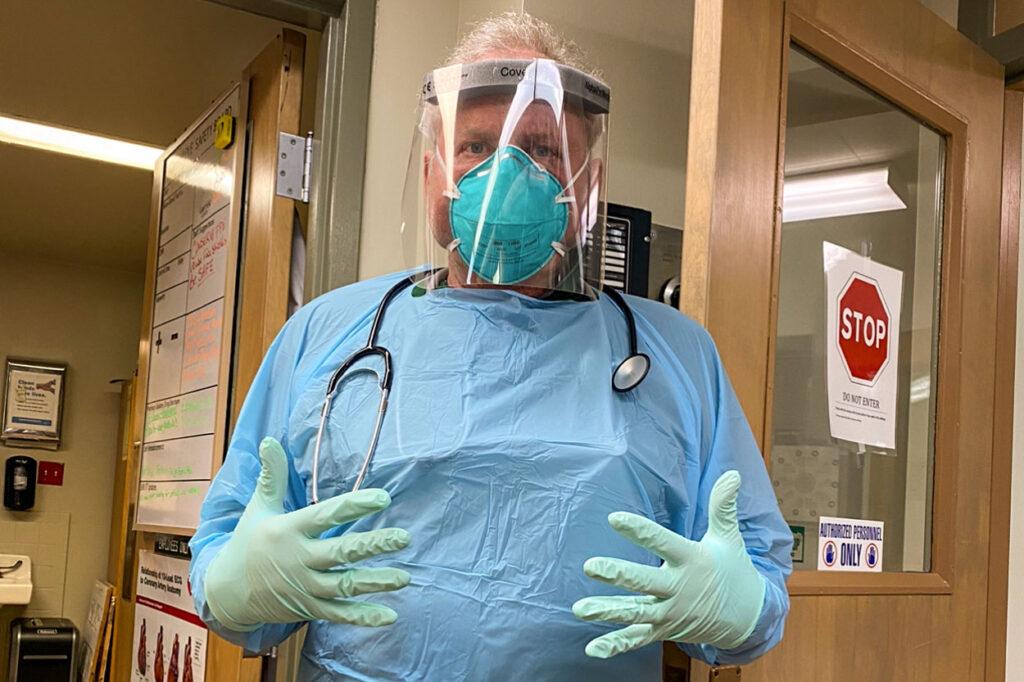

“It was a pivot point in history,” said Dr. Kurt Papenfus, chief of staff and medical director of Cheyenne County’s Keefe Memorial Hospital, on the rural, Eastern Plains. He said it’s easy to forget now that at the start of the pandemic, a mystery illness was running wild, with no vaccine available.

“In those five years, it definitely advanced science by a couple decades basically, the federal spigot opened up to pour tons of money into research,” he said.

The emergency led to one of the biggest experiments ever, he said, to develop vaccines. But before they were available, he caught coronavirus, he told CPR in 2020.

“The ‘rona beast is a very nasty beast, and it is not fun. It has a very mean temper. It loves a fight, and it loves to keep coming after you,” he said.

When he got sick, he drove himself three hours to Denver, followed by county deputies to ensure he made it to the hospital, where he was admitted with pneumonia. Papenfus eventually developed long COVID, what he calls “COVID brain.”

He did bounce back and returned to work but has cut back his long hours.

“COVID was a harsh reminder that, ‘yeah, you better take care of yourself. If you can't take care of yourself, how are you going to take care of other people?’” Papenfus said.

The value of remote conferencing, the challenges of resilience and the joy of pups

We heard from other Coloradans, telling us what had changed for them. Beth Hendrix said the use of remote conferencing, via Zoom, led the group of which she’s executive director, the League of Women Voters, to become truly statewide, including folks from the plains to the Western Slope.

Before, all their meetings were in person “that kept folks outside of the metro from really taking part in leadership actions. So that is one positive thing.”

Michael Dougherty, Boulder’s DA, saw a similar silver lining: Allowing court proceedings to go virtual allowed a lot more people to take part.

“We also have victims who are scared to be in the same room as a defendant or his loved ones,” he said. “They now can attend court virtually without the defendant even knowing they're there. They can watch without someone knowing they're present.”

For some, the dark clouds of the pandemic still exist. Melanie Potyondy, a public school psychologist in Fort Collins, says she’s noticed a troubling trend with kids, “a lack of resilience, a lack of that grit that I think I saw in previous cohorts of kids prior to the pandemic.”

She said they’re now quicker to give up, quicker to write off a teacher they don’t click with. Add in a reliance on technology, which “compounds this diminished level of grit in that it's so easy to hide out behind a phone and to not have to have difficult conversations with people in person.”

We got a voicemail from Grace Markley, a Denverite from near Washington Park, who said one of the beautiful things was “we ended up adopting a miniature bernedoodle.”

She met neighbors who also adopted pandemic dogs. They hung out outside, socialized over potlucks and happy hours, connected over the canines and formed the Doodle Fest.

“This part of town is just alive with pandemic puppies. So that was something that was really special for us. And five years in, we are still going strong,” Markley said.

“Quite the journey”

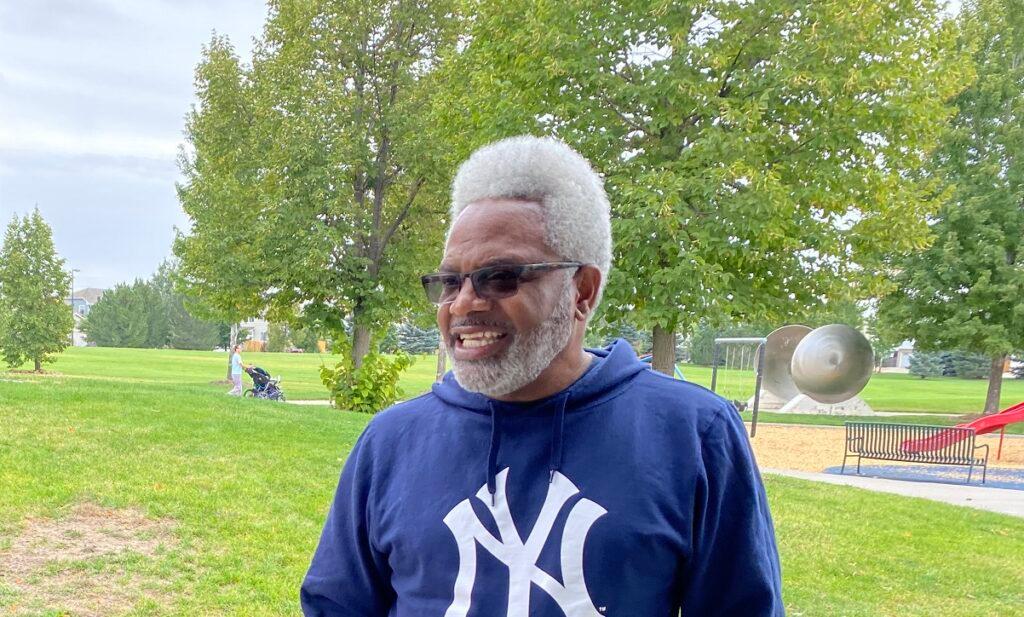

“I can't really complain. Hard to believe, five years later. Still in a little bit of recovery mode,” said Clarence Troutman, from Denver, in an interview.

He was a broadband technician with CenturyLink for 37 years. He caught the virus at the start of the pandemic, was hospitalized and on a ventilator for a time, and ended up staying two months. He retired and also developed long COVID. Five years on, it’s a mixed bag.

“I don't have the neuropathy I used to have,” he said. That’s nerve damage causing pain, numbness or tingling. “Kind of the psychological scars of everything have honestly kind of healed.”

He still grapples with chronic fatigue, brain fog and diminished lung capacity. But Troutman said a long COVID patient group he joined after he got sick still meets regularly, comparing their experiences, supporting each other. “We're still a tight little group and we're getting better together,” he said.

He’s started working out at his local rec center, which is an improvement. And he said he’s closer than ever with his son and two grandkids in Atlanta.

“I feel truly blessed every day when I think about the people that weren't able to make it through this thing or changed forever, even worse than I am. I know I'm blessed,” he said. “I'm a very lucky guy.”

Troutman said another good thing was his discovery of an inner power. “You kind of tap into a strength or resiliency you didn't even know you had until all this happened,” Troutman said. “So yeah, it's been quite the journey. Quite the journey.”

No doubt.

Elaine Tassy, Allison Sherry, Sarah Mulholland and Jenny Brudin contributed to this report.

Editor's note: This story was updated to correct a misspelling. The public school psychologist in Fort Collins is Melanie Potyondy.