About half of the U.S. Department of Education’s staff is being put on leave Friday, and President Trump intends to close the agency altogether. The dismantling began with a focus on the department’s Office for Civil Rights, which is charged with ensuring equal access to education and protecting students from discrimination.

As of last week, Colorado had 223 pending civil rights investigations, and local groups involved in some of those cases told CPR News they have received no information about whether those investigations are continuing.

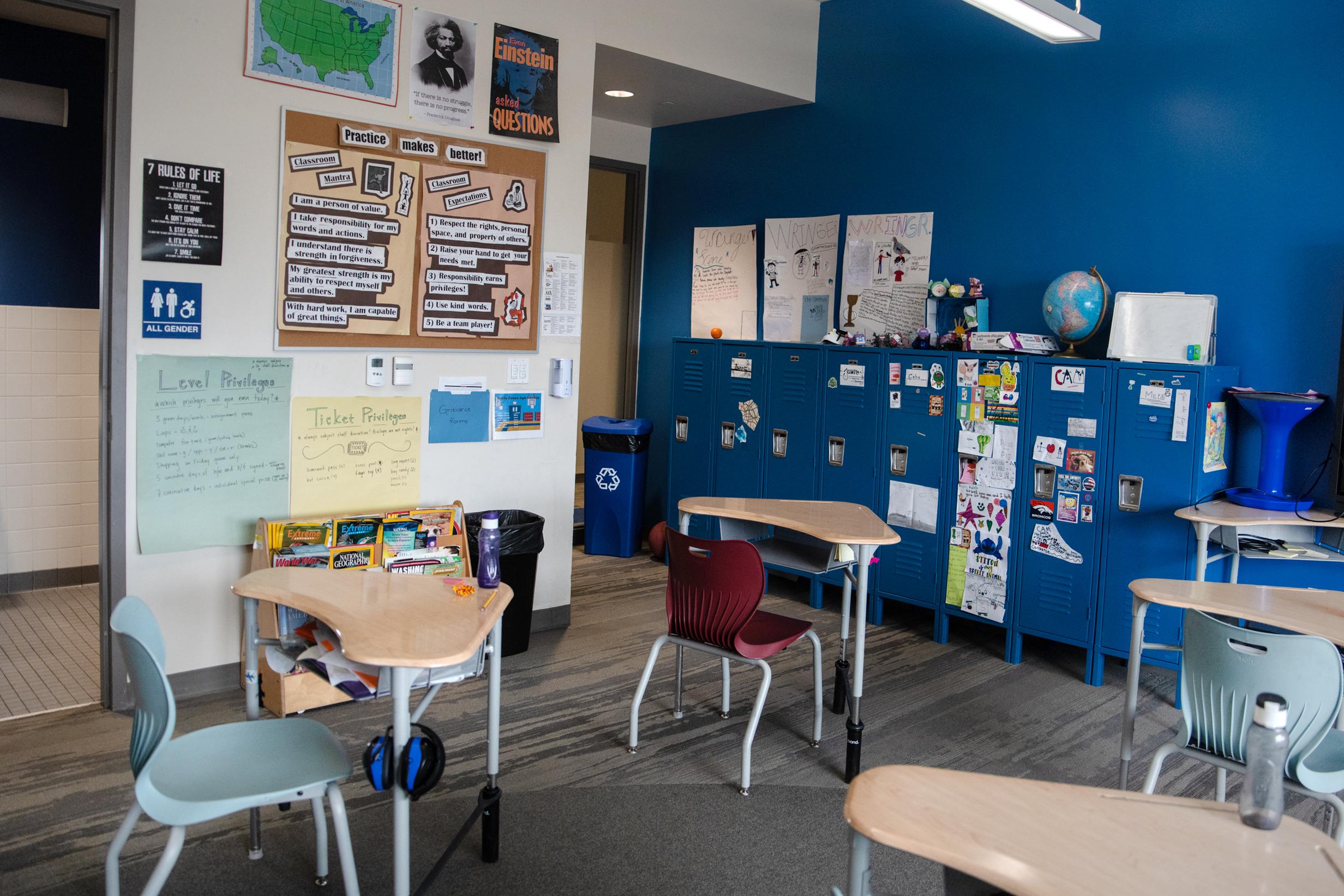

Sarah Collins, who lives on the Ute Mountain Ute reservation, is among the parents in Colorado who are worried about what the cuts will mean for their families. Her child has autism spectrum disorder and relies on a network of therapies and a special education teacher to help. She fears with layoffs and less oversight, her network of support could collapse.

“I would like for him to have professionals around him that know how to regulate him,” she said. “It's going to affect a lot of the parents' lives and livelihoods of having to accommodate what's going to be missing in their child's educational services.”

Collins is a board member of Disability Law Colorado, which pursues cases at the DOE’s Office for Civil Rights.

Emily Harvey is the organization’s co-legal director. She told CPR’s Bazi Kanani that students like Collins’ son have a legal right to services under federal and state laws.

Harvey and Kanani talked about how the dismantling of the U.S. Department of Education could affect the protections for students with special needs and disabilities.

The transcript of this interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Bazi Kanani, CPR News host: Your organization has called on state and federal leaders to protect the rights of students with disabilities from what you describe as a “reckless decision” by the Trump administration. What do you mean by that?

Emily Harvey, Disability Law Colorado, co-legal director: In these recent cuts, they gutted the U.S. Department of Education's Office for Civil Rights. They shuttered more than half of the regional offices. They're now calling on the regional office in Denver, who had over 600 open investigations in January, to take on an additional 2,200 open investigations from the offices out of Cleveland and Chicago, because those are two of the offices that were closed. So the Denver Regional Office of the Office for Civil Rights is now responsible for complaints out of 13 states instead of five.

And this leaves families with limited options to try to pursue their civil rights claims, because there just isn't the staff to handle these investigations. And on top of the investigations, the Office for Civil Rights has always provided technical assistance and training to families and to school districts, and that is now not happening because they don't have the staff to do it. So families don't know their rights and school districts don't have them to turn to understand how to serve these children.

Kanani: What are the kinds of things that the Department of Education investigates in Colorado?

Harvey: The Office for Civil Rights can investigate discrimination claims based on disability, gender, race, and they are the agency to turn to when there are issues of bullying — that falls under their purview. Service animals in school, accommodations in higher education — those fall under them, and just different treatment based on disability, segregating [kids with disabilities] in separate schools that are in shambles, those sorts of things.

Kanani: Of the civil rights cases that the Department of Education has handled from Colorado in the past, what's come out of them?

Harvey: There are lots of cases that have come out of Colorado with the Office of Civil Rights. One that sticks out in my mind is we filed a complaint with the Office of Civil Rights around children's school days being shortened inappropriately because of disability-related behaviors. And as a result of that, the school district had to change their policy, but we were also able to take the law that they established around what has to happen and get it put into state law so that kids have more protections in school.

Kanani: Another group called Ready Colorado is supportive of the initial cuts at the Department of Education. Its leader, Brenda Dickhoner, told CPR News that she agrees that all of the statutory funding to students should be maintained, “but our goal is driving dollars into the classroom and reducing administrative staff.” What do you say to that argument?

Harvey: Yeah, I agree that we need to cut administrative costs and spend more money on serving children. And I think that in order to do that in a way that effectively serves students, there needs to be a true look at where there is waste, not just full cuts of complete offices that are investigating civil rights claims. There's been a lot of talk of sending education back to the states, and there's an argument that it should be with regards to civil rights enforcement. In order to do that effectively, you would have to have a plan for states to actually be able to investigate those types of complaints and handle the volume that would be coming their way. And we don't have that.