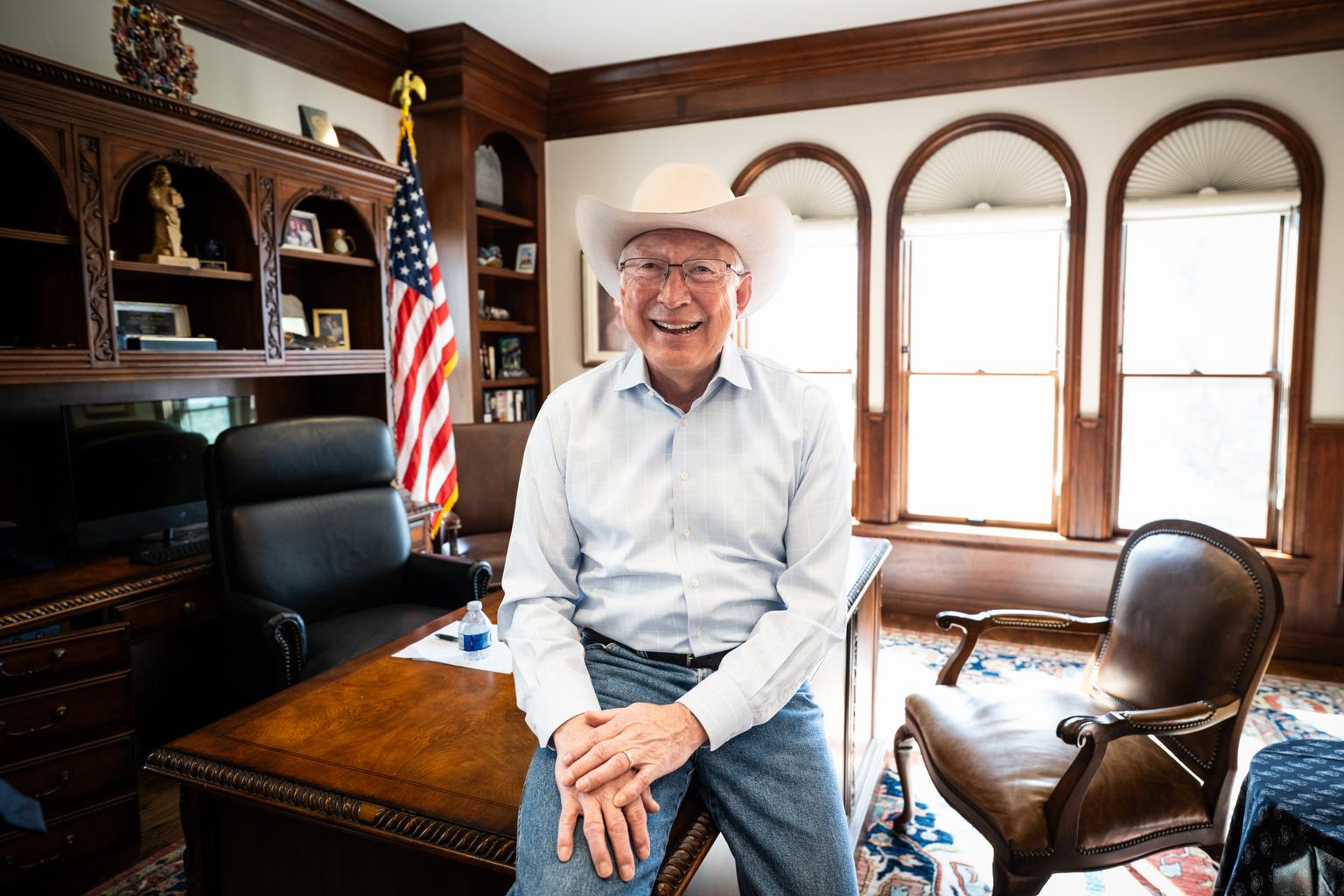

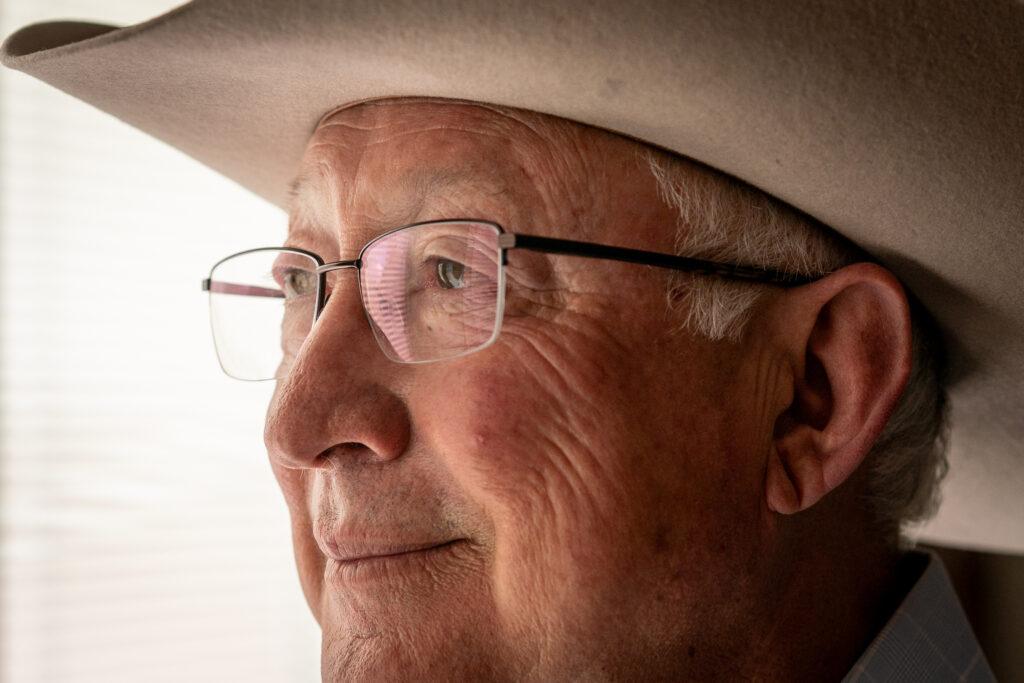

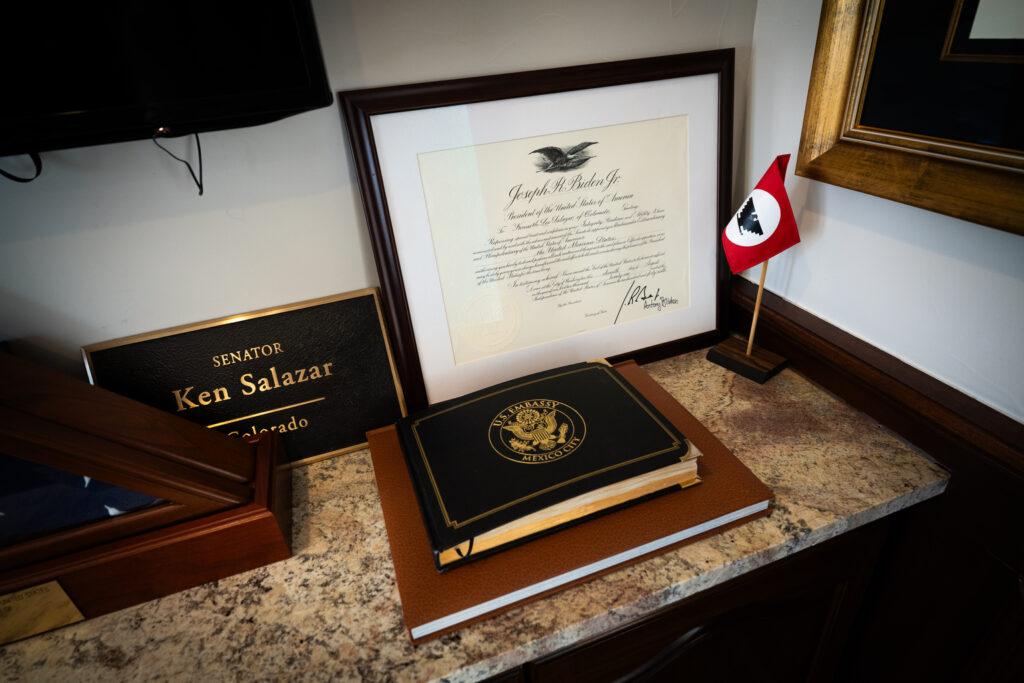

On the surface, there doesn’t seem to be a lot that Ken Salazar can do these days to resolve the relationship between the United States and Mexico, something he calls a “misunderstood” relationship, leading to national and economic security issues between the two nations. After all, he’s months removed from his position as the U.S. Ambassador to Mexico, ousted after Donald Trump returned to the White House last November, and as of yet, he says he hasn’t had a conversation with his successor there, Ronald Johnson.

“I've offered him my assistance in whatever way I can – I doubt that it'll be taken up,” Salazar said, alluding to the philosophical differences between his work under former President Joe Biden and the Trump Administration.

“Our problem in our relationship, the United States and Mexico is one that can only be addressed by giving it attention, by making sure that we're working as friends, as partners with respect for each other and understanding the history of both countries,” Salazar said. “That's where we'll find the greatness of North America and that's where it's going to come from. But it's not going to come under this president.”

But as a man who’s overcome long odds previously, whether it was becoming Colorado’s Attorney General, or winning a seat in the U.S. Senate, and later becoming the Secretary of the Interior, Salazar remains undaunted, saying “I am going to work my heart out to finish the job that I've been working on since I went to college, and that's to create a greater unity in the United States of America among all people to celebrate the diversity of who we are as a country and not to demonize and divide this country.”

Speaking with Colorado Matters senior host Ryan Warner from his home in Denver, Salazar addressed a number of topics, including the impact that President Trump’s proposed tariffs will have on the Colorado economy, his work fighting against the Mexican cartels to keep drugs like fentanyl out of the U.S., and his relationship with new Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum.

The Impact of Tariffs on Colorado:

“First of all, agriculture in Mexico and Colorado and the United States for that matter are intertwined. The supply chains, to use a techno word, are integrated between the United States and Mexico. So tariffs mean higher prices. It means that if you're buying that Ford truck or that Caterpillar tractor, whatever you're buying, you're going to be paying 25 percent more because all the companies are going to pass this on to the consumers. So everything that's going to be hit by these tariffs is going to mean a very significant increase in the price that we consumers in the United States are paying for these products."

Fighting the Mexican cartels:

“I probably spent 40 percent of my time working on security matters, chasing the bad guys, catching them, getting 'em back to the U.S. and Mexican Marines and soldiers were dying in those operations. We were doing it with intelligence from the United States and we were involved in operational support to have them get to success and the number of extraditions, these are fugitives bad guys that we have wanted for a very long time to bring to justice under American law in American courts to serve their time in American prisons.”

On the disconnect between the Biden Administration's work at the border and the perception of the public:

"With the election of Donald Trump to a second term, they made the border a political opportunity. Under President Biden's leadership, frankly, there wasn't enough attention given to the border at the right time, and not enough attention given to migration and to the flows of migration. But if you look at the numbers just on migration flows, we were able through policies we finally got the president to sign off on in the final year, to bring the flow of migrants coming to the border to a lower number than they had been in the final months of the first Trump administration. We were able to do that, but it came too late in the game.”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity

Ryan Warner: Following your ambassadorship, how do you understand the relationship between Mexico and Colorado specifically? I think we can talk trade and we can talk people, so given the tariffs that are looming now, April 2, why don't we start with trade?

Ken Salazar: First of all, agriculture and Mexico and Colorado and the United States for that matter are intertwined. The supply chains are integrated between the United States and Mexico. And so for me, one of the greatest goals that I had, and one I'm very proud of, is that the United States and Mexico became the number one trading partners in the world and in the history of humanity and Colorado's trading relationship with Mexico is a very robust one in agriculture and automotive and a whole host of other things. And so I had the honor of hosting Governor Polis, the Colorado Forum, the chamber organizations that would go down to Mexico because they recognized the importance of the trade between Colorado and Mexico.

Warner: I think the agricultural aspect is maybe better known, but the auto parts aspect and energy is really powerful between Mexico and the United States. Will you just say a bit more about that?

Salazar: In the automotive and agricultural world, if you will, think companies that we take for household names here, John Deere, Caterpillar, General Motors and Ford and it just goes on, they are integrated in producing the vehicles, the freight liners in Mexico, supplies that come from the United States that are manufactured here, that are then put into factories in Mexico, assembled there and then brought back here. And so the auto industry is one of the most important sectors of the integrated economy between Mexico and the United States and very much affects us here in Colorado.

Warner: What would tariffs mean, do you think? I'm curious your perspective if indeed on April 2 they go into effect. I think it's a 25 percent tariff.

Salazar: Tariffs mean higher prices. It means that if you're buying that Ford truck or that Caterpillar tractor, whatever you're buying, you're going to be paying 25 percent more because all the companies are going to pass this on to the consumers.

Warner: Speak to the person who heard that a lot of the assembly happens in Mexico and thinks that should happen here; bring that back to the United States.

Salazar: It's happening both ways because much of the supplies that go into putting these vehicles together are manufactured here in the U.S. so it's an integrated economy. The integration of the North American economy under the United States, Canada, Mexico Free Trade Agreement, USMCA, is one of the stellar developments of the North American continent and it's that integration that is so important that's going to guide the future of the relationship between the United States and Mexico for the next century and beyond, and it's what this current president is essentially assaulting by trying to unilaterally impose tariffs and do other things that are in contravention of the USMCA, which he himself signed as president in his first term.

Warner: It seems to me that the new president in Mexico, Claudia Scheinbaum has found a way to, if not work with President Trump, at least meet him where he's at. So far the tariffs have not gone into effect and it's seen that that's a function of her skills diplomatically. Have you met the new president? What is your sense of her leadership thus far of Mexico and how that affects the United States as its neighbor?

Salazar: I do know her well. She was mayor and governor of Mexico City, and so you start thinking about a city of over 9 million people and she did a very effective job, so she and I worked on a lot of different things on climate, on renewable energy and a whole host of things. She came to the residence to visit me on a number of different times and I went to her office and visited her a number of different times. She's the first woman elected president in any country in North America. We have high expectations. I have high expectations for what she will do.

I think she's on the right track. She is standing up for Mexico, she's being strong for Mexico but recognizes some fundamental principles that we are very much in agreement on, and that's the integration of the North American economy as one economy addressing the security issues, including the violence and the cartels in Mexico, which is something that we worked on very hard, which she worked on very hard when she was mayor of Mexico City and now she's taking that formula across the entire country of Mexico. So I'm optimistic about Mexico.

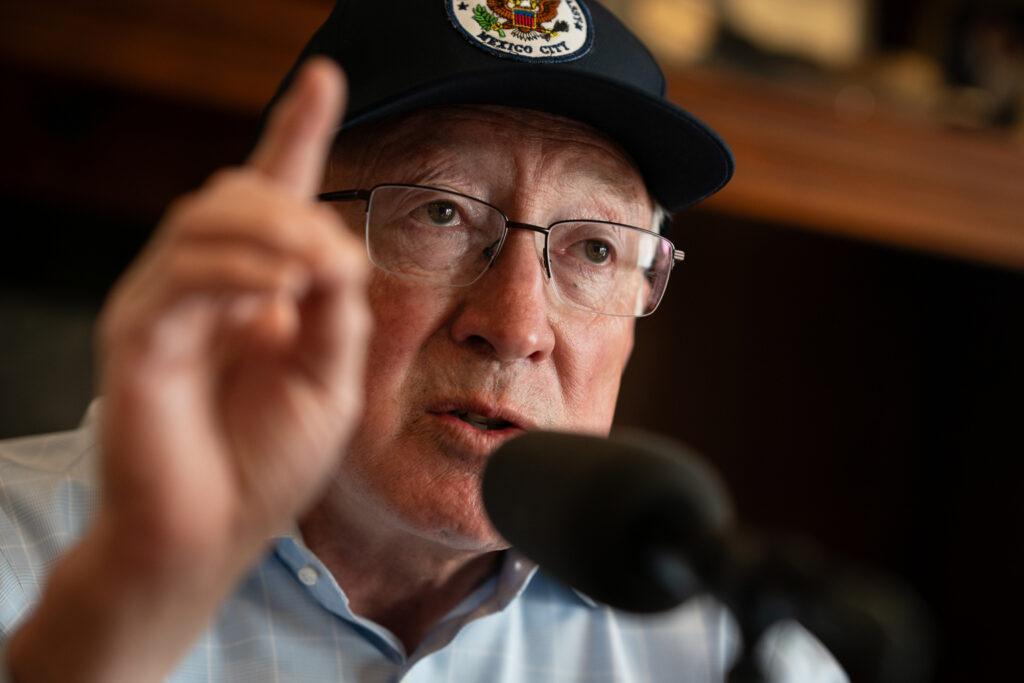

Warner: Are the heads of the cartels, are the truly powerful people in the cartels being held to account?

Salazar: As ambassador I probably spent 40 percent of my time working on security matters, chasing the bad guys, catching them, getting 'em back to the U.S. Mexican Marines and soldiers were dying in those operations. We were doing it with intelligence from the United States and we were involved in operational support to have them get to success and the number of extraditions, these are fugitives bad guys that we have wanted for a very long time to bring to justice under American law in American courts to serve their time in American prison. So the leadership of the Sinaloa cartel, we have most of them here. Other cartels in operations that were conducted are now here. The operations that have been blessed now by President Claudia Scheinbaum have resulted in even more of those cartel leaders coming here to do their time in the United States.

Warner: Who else was on your most wanted list that remains?

Salazar: The Chapos and the Chapitos, right, it’s the leadership of the Sinaloa cartel. There are still some fugitives of the law right now and they're being sought after. There are others who are sitting in prisons and their maximum security prison in Mexico City that the United States very much wants and that hopefully, the Mexican government will agree to extradite those people to the United States to face justice here.

Warner: I think we can't talk about security safety without talking about fentanyl. I think that when we hear fentanyl, we might think immediately of the border. It turns out in fact that China is the most important supplier of fentanyl to the United States. Mexico comes in second. China has enacted some reforms as I understand it, that may mean fentanyl coming out of Mexico becomes more and more important. Can you help us understand how much fentanyl is crossing the border?

Salazar: Well, fentanyl is coming to the United States from Mexico, but it's coming to the United States from other places as well, including ports in California and the port in New York. So we know fentanyl is coming in from mostly Asia and its precursors that come in, and then there are manufacturers of fentanyl both in Mexico as well as here in the United States who manufacture the fentanyl and then sell it. The fentanyl that's manufactured that crosses the border is a very significant amount and that's why the deaths of the hundred thousand Americans that died here before last from fentanyl, it's such an important security imperative for the United States. But that's why we were involved with Mexico to get China to participate in a global coalition to fight fentanyl, and I can say we were successful. In fact, if you look at the numbers of fentanyl deaths in the United States, they're down about a quarter over what they were even a year or two ago. And so the global effort that has included Mexico helping lead the effort to talk to China and get China to do the reforms, this is stop the precursors from coming over to the United States. That's something that we were very successful in getting done.

Warner: Okay to people. We've talked about trade, we've talked about illicit drugs. It just seems to me that the conversation about the border, who is able to cross, who is not, who is in the country legally, who is not, what pathways they have, that discussion has become so ideological and so charged that it's hard for I think the everyday American to separate fact from fiction, to separate ideology from reality. What is your picture of human aspects of the US-Mexico border as we speak?

Salazar: My view is that people in the United States and Mexico have to understand the border much better than we do, and the people of both countries have to understand the history of our relationship much better than we do. You have to remember, eight states of the United States were lost by Mexico as a result of the Mexican-American war that was in 1848. Ever since that happened, what you've had is a hodgepodge of activity around the border with no effective joint planning effort between the United States and Mexico. And that's because the border was a creation of the war. It was a consequence of the War of 1848. And so people need to recognize that history. And I'll just give you one anecdote: the first president to ever visit Mexico City from the United States was President Truman in 1947, March 3, 1947. That's because the relationship was one that was born out of war.

But what happened in World War II? Mexicans were involved in every aspect as the closest ally of the United States against fascism, against the Nazis. They had soldiers from Mexico dying in the battlefields serving with the United States. They provided the labor here in the United States for agriculture and for the factories. And as a result of that, the high point of the relationship in a positive way between the United States and Mexico was actually reached in that alliance of brotherhood and sisterhood during World War II.

Warner: I think what I hear you saying is that the border between the U.S. and Mexico is not human geography. It's not the geography of families and relationships. It's not that reflective of the longer history. It's a kind of artificial creation from a conflict.

Salazar: It's an artificial creation of a conflict. And if you fast forward to the last 30 years, it's become the political issue for both parties to battle over, especially the Republican party, to make the border a border in crisis all the time. And so the rest of the relationship that's a U.S.-Mexican relationship is one that has not been understood. If you ask most Americans about Mexico or about the Southeast, about states like Campeche, about states like Tabasco, other places, they don't know much about what happens in Mexico. You may even ask about avocados. Do you know all of our avocados, most of them come from Mexico, or tequila or beer. People don't get that because the politics and theology of the United States have essentially defined the relationship as one of a border in crisis, and that's all. It's a dereliction of duty, a failure of leadership of our politicians in the United States.

I worked hand in hand with President George W. Bush and Republicans like Senator John McCain, but also Democrats like Ted Kennedy to try to get a new sense of an immigration reform package passed and we got it passed in the Senate. It was killed in the House because Republicans saw a border in crisis as being a political opportunity for them, and that's what happened again now in 2024 with the election of Donald Trump to a second term, they made the border a political opportunity.

Warner: Were they smart to do that? They won.

Salazar: Well, they were smart and they did win, and they won for a lot of reasons. But one of them is a fact that the border is a broken border and it needs to be fixed and it needs to be modernized, and it should take a bipartisan effort on the part of the United States leadership, and it also takes a binational effort. So Mexico has to be part of this, that if we're going to create a modern border between the United States and Mexico across these 2000 miles of border between our two countries, we have to work together to modernize the border. It is antiquated. It is old, it is insecure, and it's a threat to our national security.

Warner: Let's explore that. What is unmodern about it? Give me an example of what you mean.

Salazar: You go through any of the dozens of ports and you have thousands of vehicles standing in line a lot of times for six hours at a time just trying to cross the border. So think about the environmental pollution that's coming through there. You have trade that goes both ways where you have things that are illegal coming from Mexico to the U.S. and from the U.S. to Mexico. You have 70 percent of the guns, major assault weapons, military-level assault weapons that are used in Mexico or manufactured here in the U.S. The border is not secure. You have illicit products that are used in criminal activity going both ways across the border from Mexico to the U.S. and from the U.S. to Mexico.

Warner: You were in some of the highest seats of power to be able to influence some of this, certainly the U.S. Senate. You had President Obama's ear, you were ambassador to Mexico. How much of this falls at your own feet? How much do you feel that there was more you could have done?

Salazar: I think there's a lot more that has to be done and a lot more that I intend to do because I think these problems have been overwhelmed by the politics of both parties at different times. President Bush, as hard as he tried, couldn't get immigration reform in the modern border done, but we had Republicans and Democrats who wanted to do it. President Obama wanted to do the same thing, but again, it didn't happen then. President Trump didn't care. All he wanted to do was to build a wall. And then under President Biden's leadership, frankly, there wasn't enough attention given to the border at the right time. And not enough attention given to migration and to the flows of migration. And by the time that the administration in Washington woke up, the Republicans had their campaign plank ready to go, and they did everything they did with it in the 2024 election.

But if you look at the numbers just on migration flows, Ryan, we were able through policies that finally we got the president to sign off on in the final year, able to bring the flow of migrants coming to the border to a lower number that they had been in the final months of the first Trump administration, but it came too late in the game. I'm an ambassador in Mexico City. I'm thousands miles away from Washington, DC, but to get the powers of Washington both in the White House as well as in the Congress of both chambers to do what's the right thing to do, that's been the main political obstacles to solutions on what is a national security and an economic security issue for the U.S.

Warner: Are you running for something? I hear you just then and I think, “Oh, is this man running for president?” I walked into your office, secretary, thinking, “Oh, maybe he's going to run for governor.” But I have to tell you the answer I just heard sounded more presidential than gubernatorial.

Salazar: Ryan. Let me just say, I am going to work my heart out to finish the job that I've been working on since I went to college, and that's to create a greater unity in the United States of America among all people, to celebrate the diversity of who we are as a country and not to demonize and divide this country. And right now, what I see with this president and with his attacks on diversity and inclusion, it's counter to everything that I stand for and how I manifest that passion. I'm going to do it first by writing a book, which I'm working on right now.

And I hope that book is one that helps elevate the understanding of the people of the United States and the people of Mexico on how we are one family. I wanted to get that done and how I do that, first it's going to start with a book. I'm spending some time with my family, catching up with my family. I've been like a soldier of war. It's a long way from Denver, Colorado to Mexico from the San Luis Valley, Los Ricones, our ranch to Mexico. But I've done it and I'm back, and the same passion that burned in me when I got into public office a long time ago and the offices that I held still burns brightly.

Warner: Well, a book is often a first volley when you're running for higher office, so I have to ask, what comes after the book? Is it just that you don't know yet?

Salazar: I honestly don't know yet. The four years in Mexico were intense. We were battling cartels. There were many sleepless nights. We frankly were involved in the operations going after these guys. We were working to shore up the economy, both in the United States and looking at durable long-term solutions that will help the development of southeast Mexico and into Central America. That's what we worked on night and day. This job of the jobs I've had was the hardest, most consequential of all the jobs because I had to deal with the political reality of both countries, and it was a very difficult political reality.

Warner: What do you call the Gulf?

Salazar: I call it the Gulf of Mexico. I, in my time as Secretary of Interior, negotiated the transboundary agreement for the Gulf of Mexico that basically divided the resources between Mexico and the United States. Why would somebody, as this president has done, change a name just to create an assault on those groups of people that he doesn't like? In the same way that he changed Mount Denali back to Mount McKinley or Fort Liberty back to Fort Bragg, there's a complete misunderstanding of the history of this country that is being implemented into the policy of the United States of America right now.

There's no recognition at all that African-Americans were brought here as property and enslaved, the Native Americans were slaughtered and killed and put into trails of tears all over the country, the Mexicans were conquered, that women were left out, that people who were different and other ways were left out, and that's the assault that is taking place right now against the American people and the progress that we've made on civil rights.

Warner: Has there been too much focus on what makes us different and what divides us though?

Salazar: So there was a great governor who's still here with us, Roy Romer, probably the greatest governor of Colorado, at least in my lifetime. This guy is a real deal from Holly, Colorado, of German descent, elected in ‘86, but through his governorship, what he would say about the United States, what he would say about Colorado, is that we needed to not just tolerate our diversity, we needed to celebrate our diversity, and that's what's at stake right now.

Warner: What was the reaction around you in Mexico City to the election of Donald Trump this last time?

Salazar: I think people were very concerned and rightly so, very concerned that they'd go back to a relationship of great friction, inattention, a lack of understanding. Trump never went to Mexico one time as president of the United States. Trump went to Mexico only when he was running for office in 2016, and that's because he wanted to go counter a visit that Pope Francis made to Mexico at the time where he was talking about migration and a whole host of other things. And so our problem in our relationship, the United States and Mexico is one that can only be addressed by giving it attention, and as I said, a thousand times in Mexico, making sure that we're working as friends, as partners, and understanding the history of both countries. That's where we'll find the greatness of North America, and that's where it's going to come from. But it's not going to come under this president.

Warner: It's not going to come under this president. What makes you so sure?

Salazar: Donald Trump has called lots of people by lots of different names, but he has often referred to Mexicans as criminals, as rapists. He's given countries the names of names that I'm not going to say on your radio show, but we know where he's coming from. He's trying to take us back to an era that was there perhaps in the 1930s and 1940s. You talk about the KKK, you talk about the hate that you see from people who hate other people just because of who they are. That's where this president is taking the United States to right now.

Warner: I want to ask you about Jeanette Vizguerra who came to the U.S. from Mexico City in 1997. Undocumented mother once named to Time’s 100 Most Influential list, and just before we sat down to record this, she was detained by ICE in Colorado.

Salazar: The mass deportations that Donald Trump is ordering in his administration are going to hurt a lot of people, a lot of people. I went to a hospital in Guatemala to visit the survivors of migrants from the Guatemalan Highlands who had crashed. (171 people were on three trucks) 56 people of them had died piled into a cattle truck. There were three tractor-trailers in this caravan. The first two went through, the third one crashed on a curve. I went to the ICU unit to visit some of the survivors. There was a woman there, 21 years old, her name was Vanessa. She was on her way to Wisconsin to see her husband who'd been working at a Wisconsin dairy farm for a very long time. She had not seen her husband for a couple years, and she had her son, a young boy named Damien, who had never seen his father, and yet the father, the husband, was working in our dairy farms in Wisconsin.

You ask Idaho, Wisconsin, any of the 50 states, where are your landscapers coming from? The people who were working in the dairies, the people who were working in hotels? In that process, because of our very broken immigration system that's been there now for 30, 40 years in its broken state of affairs, you are hurting a lot of people like this woman. She lost her scalp and was in the hospital almost dead with her young son next to her. So what Donald Trump is doing with his policies is he's going to hurt a lot of people. There are over 10 million people who live in the shadows of America today. Those are the people we were talking about bringing out of the shadows when John McCain and Lindsey Graham at the time, and George W. Bush and Ted Kennedy and a whole host of others were arguing to bring these people out of the shadows of our society. That cause is just as clear today as it was when I made those arguments on the Senate floor in ‘05 and ‘06, ‘07 and ‘08. So there's a lot of work to be done. I think America's greatness is going to come about by solving some of these problems like the migration issue that we face.

Warner: What's notable to me about the Vizguerra case is that to this point, we have heard the administration focusing on what they believe to be the criminals and a lot of talks specifically when it comes to Aurora, of Tren de Aragua, the Venezuelan gang for instance, but in Jeanette Vizguerra, you have someone who is certainly an activist, who certainly is high profile and has been critical, but who's not part of some cartel or something. Do you think that this represents a sea change, a shift in what the administration is going after?

Salazar: I don't have any particular insight into where the administration is going other than what the president has said publicly very clearly along with the rest of his people who are running migration in the border and that is that they are going to do mass deportations. Mass deportations means in the millions and millions of people if that's where they're going to go. I don't think we yet know how far they're going to go. I think she is an example of one of those people that's getting caught up in this inertia, in this momentum to fulfill Donald Trump's promise on mass deportations.

Warner: How much contact, if any, do you have with the new U.S. ambassador to Mexico? That's Ronald Johnson, formerly under the previous Trump administration envoy at El Salvador.

Salazar: We have communicated by my offering to help him in any way that I could. I have a Mission Mexico briefing, which I've shared with U.S. senators and members of the House on both sides of the aisle, and I shared that with him, told him that this was work that had been accomplished by Mission Mexico during my time, and so I've offered him my assistance in whatever way I can. I doubt that it'll be taken up, but if he wants help, I'm happy to advise.

Warner: Before we go, a lighter question, what did you miss in Colorado? Maybe we should talk about food. What did you miss food-wise in Colorado? What do you miss now food-wise in Mexico,

Salazar: The Mexican food in Colorado is my favorite Mexican food. I talk about Las Delicias or El Paraíso, La Grande Mexicana. So many restaurants that I've known here in Denver or down in the San Luis Valley, in the town of Antonito, Dos Hermanas and the Dutch Mill, it's the best chili in the world. So I must say, even though I was the United States ambassador of Mexico, my favorite food is Mexican food here in Colorado. What I miss from Mexico in terms of food, they have great cuisine, lots of wonderful restaurants. The Mexico City metropolitan area now has almost 26 million people and it is growing because people from all over the world are coming there because of its restaurants. It's quality of life, its security, its arts. It's just an amazing place.