Imagine your novel about farmers fleeing the high plains during the Dust Bowl is about to be published. But another book — one partially based on your notes — comes out first. It’s John Steinbeck's “The Grapes of Wrath.” Publication of your book, “Whose Names Are Unknown,” is canceled.

This is exactly what happened to the late author Sanora Babb.

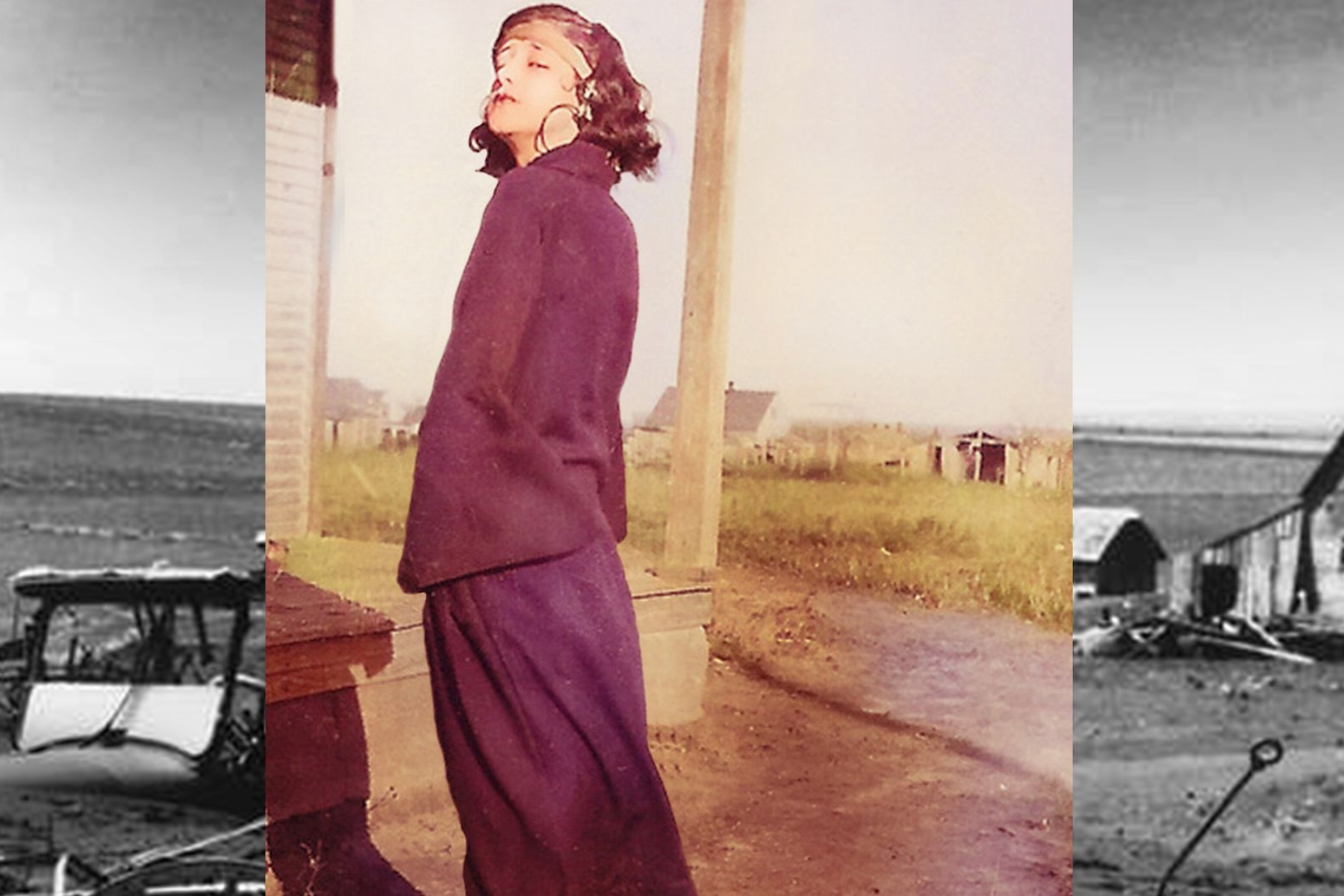

Her inspiration began as a child in Southeastern Colorado after her family moved to a dryland farm in Baca County in 1914.

She described that time in her life as “a sense of living on a grand earth under a big sky, not within walls. The darkness on the plains was as black as space. And the stars so thick and brilliant they seemed touchable while they seemed eons away. All of this, mysterious and awesome ... Perhaps it was the bigness of the plains and the sky that stretched my thoughts.”

If you go to Baca County today, it’s possible you might meet long-time farmer and rancher Tim Hume. For some years he farmed the land Babb’s family once homesteaded near Two Buttes, not far from the Kansas border. Life there was a struggle for them.

Furrows carved by modern-day farm equipment now line the dry dirt and stunted patches of sorghum grow in the huge field where Hume said the Babb family had lived. Other than a few shards of broken pottery and glass, there’s nothing left to show that a home was once there.

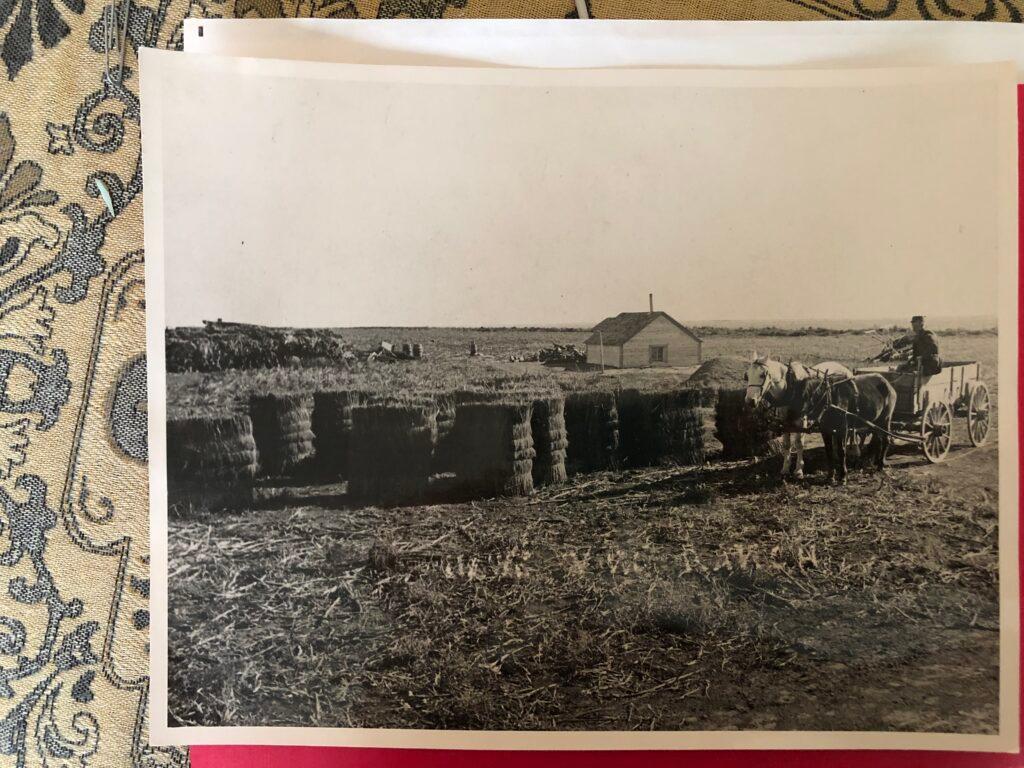

Hume’s grandparents knew Sanora Babb when she was older because coincidentally, they were neighbors in the Hollywood Hills of California. He has an old photo of the one-room dugout home where the Babbs lived. The house is called that because it's partially sunken into the ground.

“You can see it's a pretty small dugout for five people to live in,” he said, “There's probably three feet to the eave. On the other side, you can kind of see what they called the doghouse. An entry with stairs going down into the dugout and I think they were designed to be able to escape (the house) during a blizzard.”

The wind howls on the plains, in the winter sometimes piling snow into high drifts and in the summer dust often blows across the land. Farming was hard manual labor. Hume points to the photo, there are a dozen large cylindrical agricultural bales standing upright next to a horse-drawn wagon.

“Those are bales of broom corn, which would've been their major crop at the time,” he said. “They would've probably kept these for feed for their horses and sold the actual tip of the broom corn that was used for brooms.”

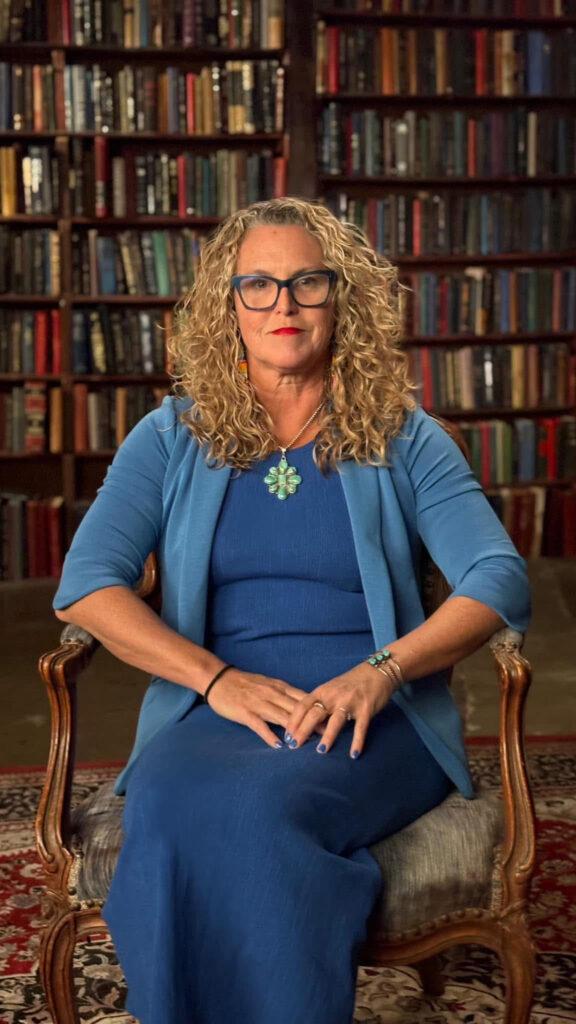

Biographer Iris Jamahl Dunkle's recent book “Riding Like the Wind” follows Babb through her hardscrabble childhood on the plains to a Bohemian life in Hollywood and beyond.

Dunkle spoke with KRCC’s Shanna Lewis.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The land is flat, it's so flat …

When you look out past a certain point, it bends on the horizon. The air smells like sage, and you can hear the sound of geese flying overhead when you're walking, you're walking on buffalo grass, so you get this crunch underfoot. It's a gorgeous landscape.

A hard life, fending off starvation while living in a house that was dug into the land

There were four of them, plus her grandfather living in a very small space. There were giant rats, there were tarantulas. They were farming broomcorn, which is what people were farming in that area at the time, and it was a struggle. They had one good crop and then the next year, nothing. They would go weeks at a time starving or sheep be living off hardtack, which is just flour and water mixed together. I think for her, she had to romanticize that time in her life. Her coming of age really began then for her, and she kept returning back to it in all of the books that she wrote.

How Southeastern Colorado shaped Sanora Babb’s worldview and writing

It was monumental because it was a place where she had to spend a lot of time alone. She would look up at the sky and she would see the stars. She'd see Venus and she would see this future ahead of her. She started to imagine how she would get out, how she would find another life. She hadn't yet discovered that she was a writer. She was very young living there, but she already knew that she wanted this other life that was contained beyond the dugout, beyond this place where she was living. It was so important to her and her growth.

Sanora Babb communed with the land and was immersed in the High Plains

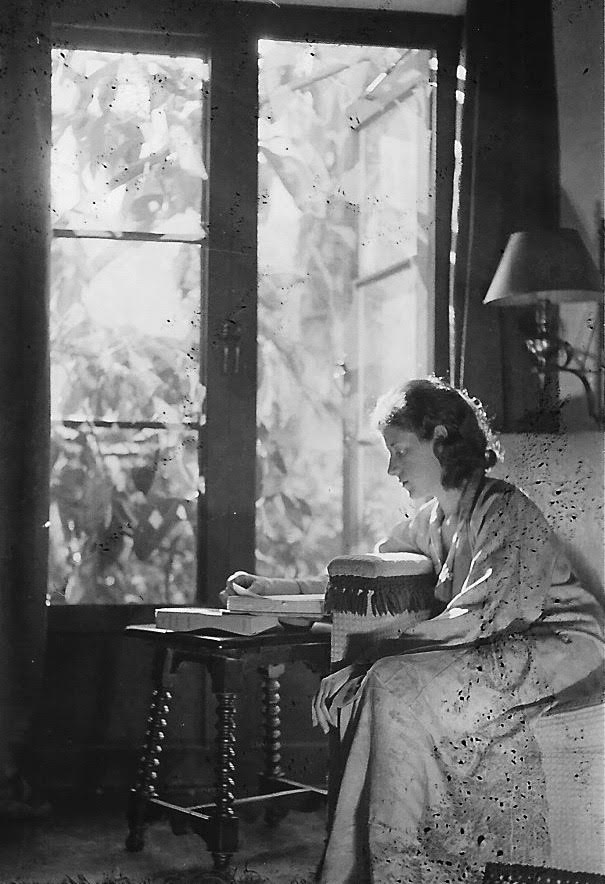

In Sanora Babb's memoir “An Owl On Every Post,” about living in Eastern Colorado, you start to see her land ethic, her idea that in order to survive in this kind of place, humans had to live in communion with nature rather than working against it. She wrote:

I've always felt grounded in the plains. The impact of those years is still potent. I treasure the deep influence of those years, a sense of living on a grand earth under a big sky, not within walls. The darkness on the plains was as black as space and the stars so thick and brilliant. They seemed touchable while they seemed eons away. All of this mysterious and awesome long before I read that everything in the universe is connected, that all life is one I knew intuitively when I was seven years old. This was an awareness, not a discovery. It gave me a mystical sense of being in the universe related belonging as transient as a flower, but just as welcome. It gave me freedom from the need for specific beliefs and dogmas. It gave me tolerance. Perhaps it was the bigness of the plains and the sky that stretched my thoughts.

Did Sanora Babb exaggerate or embellish her memories?

If anything, she smoothed them over, so they weren't as horrific as they were. But the truth is, much of what you see in an “Owl On Every Post” is vanilla-flavored compared to what actually happened. Not that the writing isn’t beautiful, but she took out a lot of the violence that she experienced from her father. She took out the amount of starvation they suffered and some of the incidents with animals. It was just all calmed down. So she didn't really embellish it into the extreme, which you'd think nowadays people would make it seem even more intense. But I think Sanora Babb was always facing the fact that people wouldn't believe the atrocities that she had faced. The woman had so much fortitude, she had overcome so much. But every time she'd say this is what my father was like, the editors would say, “That's not believable.”

Working at the migrant camps during the Dust Bowl

Sanora Babb volunteered to work for the Farm Security Administration, which was helping the 650,000 refugees who had poured into California due to the Dust Bowl. She was already working on her novel. When she went there, she would work during the day at the camp and help the refugees. She was a part of the community and really connected with everyone because she had lived in these areas that were being affected by the Dust Bowl. She knew what it was like to not be able to eat. She had experienced all of these things that the people were experiencing.

Sharing notes with John Steinbeck

Babb was creating notes from her interviews with the refugees and taking notes for herself and her boss. And at the same time, her boss had made an arrangement with the writer, John Steinbeck. Steinbeck had already written several articles about the camps. He had also tried to write two novels already about the Dust Bowl and thrown them away. So he was really frustrated. In May of 1938, he came to the camp and met with Babb and her boss at a cafe. It's at that cafe that Sanora Babb passed her notes over to John Steinbeck willingly, not knowing that that action would have a detrimental effect on her own career. Meanwhile, she had sent four chapters of her book, her manuscript to Random House.

What happened when Sanora Babb’s novel was set to be published in 1939, but the “Grapes of Wrath” came out first

Bennett Cerf was the editor and co-founder at Random House. He loved the chapters she’d sent and said, “You got to come to New York and finish your book this summer.” Babb said alright, but right now “I’ve got to keep working.” She was so dedicated to working at the camps. Meanwhile, Steinbeck got these notes and went into a frenzy and wrote “The Grapes of Wrath,” in a very short time. It ended up coming out in the spring of 1939 to huge success. I think it sold like 375,000 copies in the first six weeks, and it got a movie deal right away and became an Academy Award-winning film.

Meanwhile, Sanora Babb is still working at the camps. She finally goes back to New York and finishes her book. Bennett Cerf is thrilled with what she's written. It goes to the readers’ reports (critiques and assessments of marketability) and they do their work. All of a sudden they realize “The Grapes of Wrath” has come out and how successful it is. Bennett Cerf pulls Babb into his office. He's got the whole desk cleared, just one check in the middle. She knew something was wrong and he said, “I'm really sorry, but due to the success of the “Grapes of Wrath,” we can no longer publish your book.”

She left New York with her book contract canceled. She couldn't write. She was devastated. She had spent a decade working on this book and it was just thrown away.

How Babb’s firsthand experience living in the High Plains informed her work as compared to Steinbeck's telling of a similar story

There are huge differences between the two texts. The first difference is that the first half of Sanora Babb’s novel, “Whose Names Are Unknown" is set in Oklahoma in the High Plains. So you get to know these people as they're working the land. You get to see them living as a community, and then you get to see the Dust Bowl slowly seep into their lives as a deadly tide. You get to see the shop owners lending out too much credit, the doctors not being able to help people. You get to see the families slowly having to make this horrific decision to leave everything they know and escape to California where they are told there are these great jobs. Then you get to see when they get there, they're met with opposition not only from the big farmers but also from the citizens of California.

They're treated like complete outcasts. When they get there, because you've seen them go through so much trauma and they have no other choice but to go there, you feel so much compassion for them. You feel empathy for them. That's the worst day of their lives. That's the worst moment of their lives. So to build into a novel, this background of what it's like to experience this trauma is so powerful. It makes us really see what the Dust Bowl was like.

The other thing that's really important that she does in her book that's different, is she depicts a story where women, and children in some cases, have agency. In the “Grapes of Wrath,” women are literally pregnant and barefoot in the kitchen in the opening scenes. So it's quite a different perspective.

You also see diversity in California when they get there, just as there is diversity in California now. There are Blacks and Filipinos and Mexicans, all of them working together. They're not just flat characters. They're actually people with agency within the story.

Sanora Babb’s many literary connections included Ray Bradbury, known for authoring “Fahrenheit 451,” “The Martian Chronicles” and other science fiction classics

One of the most famous people that she connected with in the 1940s and 50s was Ray Bradbury. His work was published in the same volume of stories as Babb’s, and they discovered they were both living in L.A. They started a writing group and they were in the writing group together for over 40 years. What was really heartwarming was how much he respected her as a writer. He thought she was really one of the best writers he'd ever read. He wrote her these letters saying, “Stop doing everything else and just spend your time writing so that we can read more of your stories.”

Intimate relationships with other well-known writers including Ralph Ellison, author of “Invisible Man”, literary critic and essayist

She had intimate relationships with several writers, but one that is noteworthy is her relationship with Ralph Ellison. They met through the Writer's Congress and they fell head over heels for one another right away, but they also were intellectually connected. They would write to each other about stories and about literary craft, and they would share work with one another. In fact, Sanora Babb saw an early draft of “Invisible Man,” and he read “Whose Names Are Unknown.” He gave her these incredible comments about how he loved her Black characters and how she should emphasize the women and children even more. It was just beautiful to see that correspondence. Before my work, biographies about Ellison have featured this relationship, but they've never shown both sides of the correspondence. So they didn't really show the equalness of that relationship. It was always like, “Oh, Babb was fawning over Ralph Ellison,” but that wasn't the case. It was nice to correct that and show them as literary equals as they were at the time.

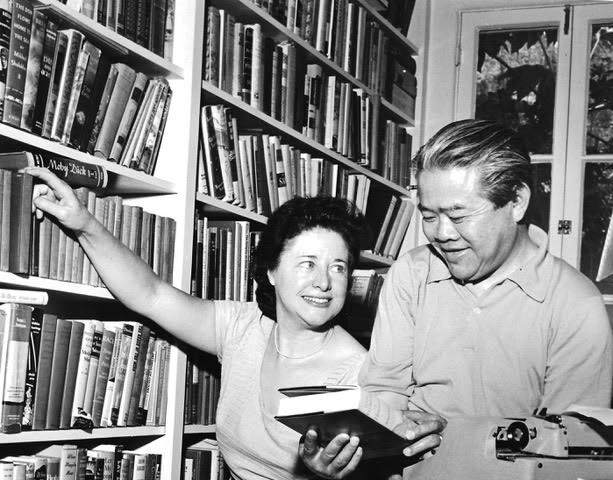

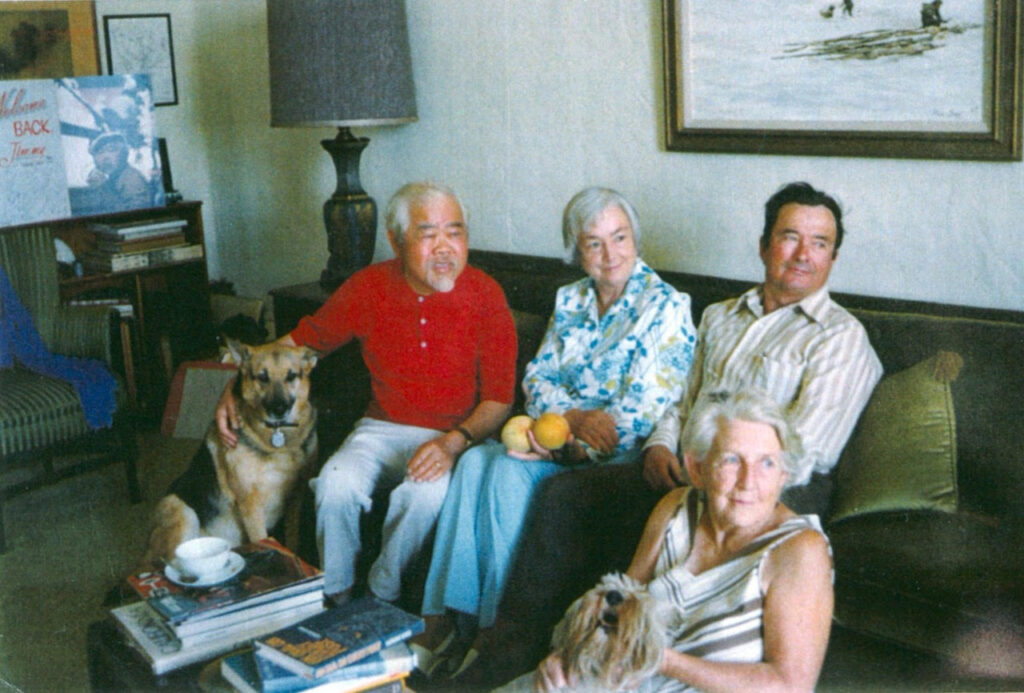

Married to acclaimed Hollywood cinematographer James Wong Howe

Sanora Babb met James Wong Howe during her early days living in Los Angeles as a writer. She was immediately attracted to him and they started dating. It was difficult. They were a mixed couple, and at the time it was illegal for them to get married, it was illegal for them to live together. It was even impossible for them to get a table at a restaurant because of the racism that was happening at that time.

They had a wonderful relationship. It was complicated by several factors. The fact that, number one, Sanora Babb grew up in a family where her mother had a troubled relationship with her father. Sanora didn't want to get married. She didn't want to have kids. It was something she didn't want to repeat. Secondly, they were dealing with the racism that Jimmy was experiencing all the time, and also that they couldn't actually be married legally. Add to that, I think Sanora Babb wanted an open marriage at that point. So they did have a fairly open marriage until they finally were able to legally get married in the late 1940s. And from that point on, their relationship started to evolve.

Howe died in 1976. Babb spent a decade solidifying his legacy. It's because of her that if you go to the Academy Awards Library, they have everything of Jimmy's there. It's amazing. And he was such a successful cinematographer. He received two Academy Awards, and he was nominated very often. If you meet anyone in the film industry, they know who he was.

Sanora Babb’s later years, finally able to focus on her own work again

After she lost Jimmy, Babb finally started turning back to her work, and she started trying to get published. But this is almost 1980, and she was born in 1907. So she's getting up there in the years, but still filled with energy – writing and publishing – but she was having trouble getting her work published. She connected with a woman named Joanne Dearcopp, who was her editor for “An Owl On Every Post.” They hit it off and over dinner one night. They were drinking glasses of wine, and Joanne made her a promise that she would keep all of her books in print and help her publish. She heard about “Whose Names Are Unknown,” and she asked, “Do you want me to help you get that published?” Sanora said, “Sure. That'd be great.” And Joanne kept her promise. So to this day all of Sanora's books are in print because of Joanne Dearcopp and that amazing friendship that they had.

Sanora Babb died in 2005, the year after the publication of her novel. Joanne Dearcopp died last year.