Editor's note: This story contains details of sexual assault and might be difficult for some readers.

It’s a situation Miranda Spencer never thought she’d find herself in. The Denver mom was going through a divorce in November of 2023 when she decided to try a dating app for the first time. She used Bumble.

“That’s one I thought was safe,” she recalled.

After a few uneventful first dates, Spencer agreed to meet a man who had been persistently messaging her.

“So I let a friend know, ‘Hey I’m gonna go out,’ and the exact words that I used were, ‘on this pity date. You can come over afterwards and hang out.’”

Those ended up being fateful words. She said she only remembers the first 20 to 30 minutes of that date.

“I woke up the next morning with my friend just kind of hovering over me, staring at me. He's asking me, ‘Are you okay? What happened last night?’ And then he went on to tell me what he walked into my home (and) the person that assaulted me was in my bedroom. I was unclothed, I was pretty incapacitated. I had vomit all over me.”

At the time, she blamed herself, thinking she’d made some bad choices.

“I was very embarrassed and ashamed and I couldn't understand why I would have a stranger in my home or how I got home.”

Spencer went to the hospital and found out she had fentanyl in her system. She also endured the invasive process required to submit evidence of a sexual assault: a nurse conducted a full body medical exam, took photos and collected DNA from her body. Those samples were sent to the Colorado Bureau of Investigation.

Sixteen months later, Spencer still doesn’t have the results and the man hasn’t been arrested.

“I was drugged, and so there's a lot of things I don't remember, and there's a lot of answers that I don't have.”

She said one of the hardest things has been waiting almost a year and a half to fully understand the worst thing that’s ever happened to her.

“It is barbaric,” she said. “It’s not fair to put that on somebody.”

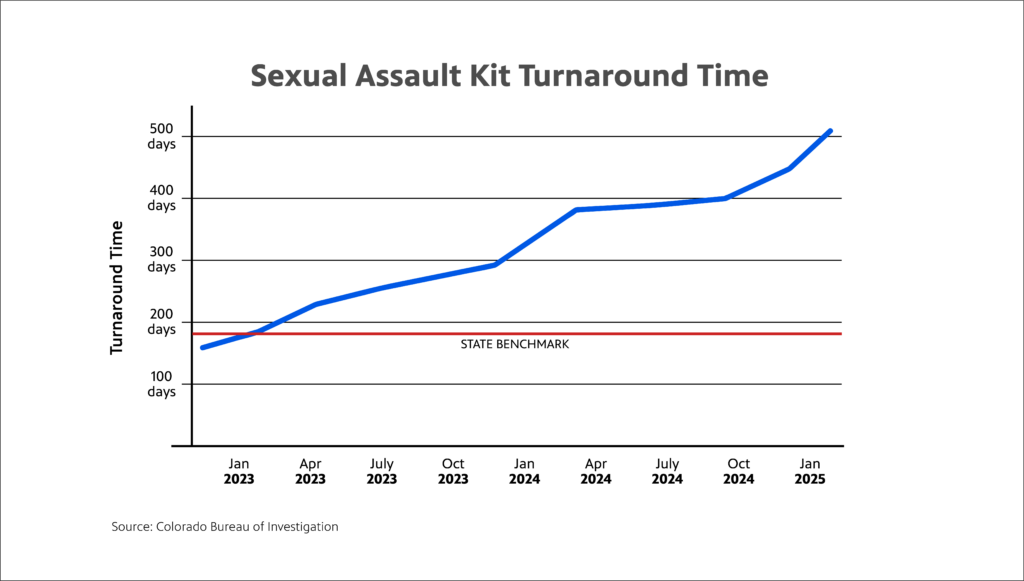

She’s not alone in this painful limbo. In Colorado, the average wait time to process DNA kits and other evidence from sexual assault cases has stretched to a year and a half, leaving more than 1,400 people waiting for their results.

In March, Spencer joined other sexual assault survivors at the Colorado capitol to share their stories with state legislators and the CBI and pressure them to fix the backlog.

“You can never imagine living in the shoes of a survivor who's waiting an endless amount of time for the results of something so invasive to go through in the first place,” Spencer told them.

This isn’t the first time Colorado has struggled with testing delays

The CBI is the state lab in charge of testing kits, and this isn’t the first time Colorado has had a backlog. In 2013, a national outcry over untested rape kits led to the discovery that local police around the state had thousands of kits they'd never submitted to state labs for testing. Evidence sat on the shelf because law enforcement didn't have a suspect, or the victim wasn't willing to pursue charges.

The CBI eventually collected 3,542 kits from local departments and the state earmarked extra money to allow its scientists to work through the backlog. It takes about four to six weeks to process a kit from start to finish.

By 2016, the CBI had managed to clear all those old cases and the legislature said, going forward, sexual assault DNA evidence should be processed within no more than six months.

But in the following years, Colorado's wait times started to creep up again. Law enforcement was sending all their kits to the state lab, but staff limitations and high caseloads left them sitting on the shelf for longer and longer periods, in some cases beyond the state guidelines.

Chris Schaefer, CBI’s outgoing director, said the Bureau started working on a plan to increase staffing several years ago. In 2022 they brought on five new scientists, but it’s a slow process. New hires must go through one-and-a-half to two years of training before they can start processing samples on their own.

And that effort to ramp up staffing was derailed when the CBI was hit by “the perfect storm,” in Schaefer’s words. First, a number of DNA scientists either left the job or took protected leave for family and other reasons. Then came allegations of misdeeds by one of its own.

An intern research project uncovered discrepancies in the work of CBI forensic scientist Yvonne “Missy” Woods. After investigating, CBI believes Woods may have manipulated more than a thousand DNA test results in criminal cases over decades. She is currently awaiting trial on more than 100 criminal charges.

“Because of that, we had to shut down, basically, 50 percent of our DNA scientists for the better part of a year to go through and research the over 10,000 cases that our former scientist had worked — that was our number one priority,” Schaefer explained. The situation also paused the training process for the CBI’s new hires.

As CBI was dealing with those staffing shortages and the fallout from Woods, the turnaround time for sexual assault kits and evidence ballooned.

At the town hall, Schaefer acknowledged the toll that delay is having on victims and survivors and said the situation is unacceptable.

“We are not meeting your expectations, but we are committed to fixing this and we’re going to explain to you today how we’re going to fix this,” said Schaefer.

As one of its actions, CBI has brought in an outside firm to investigate, “Where did we screw up?” as Schaefer put it.

However, the situation has left the lawmakers who oversee the Bureau frustrated that they didn’t know the scope of the issue earlier.

“The Colorado Bureau of Investigation should have really been coming to us as lawmakers several years ago and pointing out this problem," said Republican Rep. Matt Soper of Delta, who sits on the House Judiciary Committee.

Instead, Soper said he only became aware of it during an oversight hearing in January.

“I was shocked when I heard a witness testify that she had been waiting over a year to get her rape kit tested.”

Lawmakers’ attention on the issue this year has been spurred in part by the revelation that the delay is affecting one of their own.

Early in the session, Democratic Rep. Jenny Willford revealed that she'd been sexually assaulted in February 2024. A Lyft driver had attacked her in front of her own home.

Willford is still waiting on evidence in her case to be tested, something she told her colleagues about in a tearful floor speech, sharing the fear and uncertainty hanging over her. She’s said the incident in the Lyft has left her haunted.

She’s suing the company and running legislation aimed at increasing safety for passengers and drivers. Her role inside the State Capitol has helped keep the issue front and center.

“I decided that I had to say something because there were probably other people that were experiencing what I did and having a position of being a state lawmaker means that when I speak up, when I bring something up on the floor, people have to listen.”

Willford said a lot of people have reached out to her with similar experiences.

“And I never saw that coming. I've been really surprised by just the volume of stories. I feel like what I've been through, and what I've reported is the tip of the iceberg.”

Survivors endure traumatic and invasive evidence collection in the hope of seeing justice

DNA evidence plays a critical role in sexual assault cases, which are often hard to otherwise prove. So any delay in testing can impact investigations and prosecutions.

“From the law enforcement standpoint, we want that evidence. We want to be able to find the suspect. We want to be able to arrest a suspect. We want to put a suspect in prison for it,” said Josh Craine, the head of investigations for the Garfield County Sheriff’s office.

He said it can corroborate other physical evidence they’ve collected and help confirm a victim’s recounting of events.

“Sometimes it’s the only thing we have,” explained Craine.

He added how frustrating it is for detectives to repeatedly tell victims they have to wait.

“The perpetrator is still out there. They could be doing this to somebody else.”

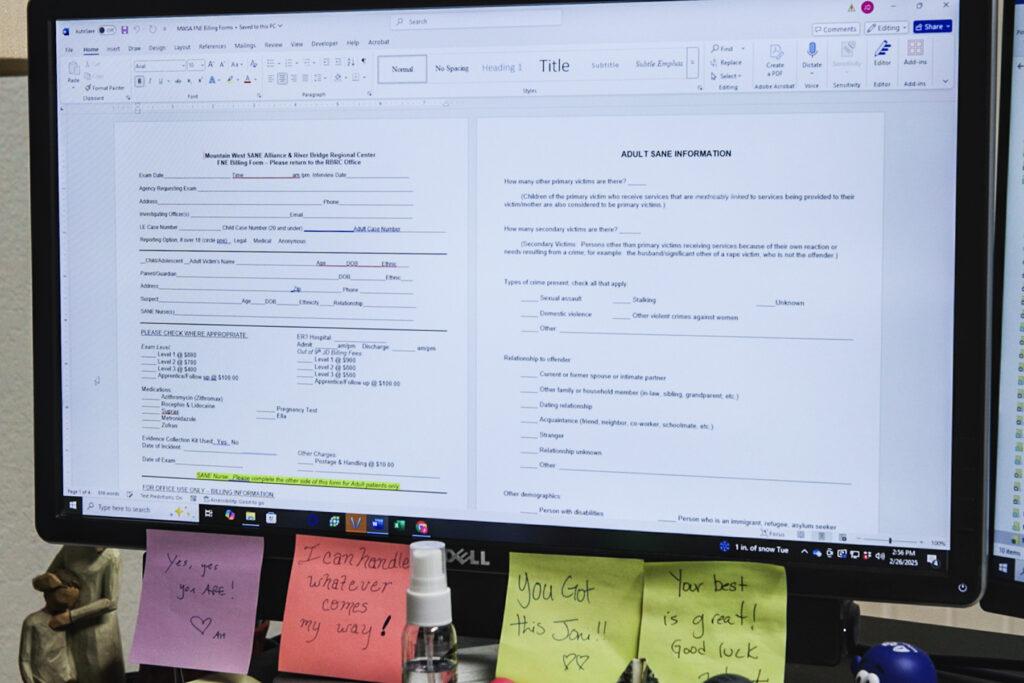

Just providing that evidence is a lot for many victims of sexual assault. A Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner gives what’s known as a SANE exam, usually at the hospital, which must be done within five days of the incident and typically takes three to four hours to complete. The nurse takes photographs, administers a full body exam, and collects any possible DNA left behind by an attacker, which can include hairs or fluids

Joni Owens is the medical coordinator for the Mountain West SANE Alliance and works out of a yellow brick house in downtown Glenwood Springs. Before she starts an exam, she takes patients to a comfy chair and offers them smooth stones with carved affirmations on them.

Her focus is on helping them feel safe and in charge of the situation.

“The first step of giving them the opportunity to heal and move past what happened to them is to give them all of the control back,” said Owens.

She said most people come in very shut down and difficult to engage; it can be traumatic to have to relive how they got their injuries, and when it’s over they have a lot of questions for her.

“Their biggest concern is the evidence kit that we collected and what's going to happen with it and when are they going to find out about it? Who's going to contact them?” she said.

For Miranda Spencer, going to the hospital and getting the exam was the start of accepting the reality of what happened to her.

“I remember just being very, in shock. I felt very weird, very disoriented. And when I first got there, I told them what happened and I was very embarrassed. I remember saying it, like, under my breath. I just didn't want that to be, you know, stamped on me.”

Prosecutors say it’s not uncommon for DNA evidence to be the missing piece they need in sexual assault cases before they can formally press charges.

“To have to wait a year and a half before we can give them an answer falls far short of what we should be doing for victims of sex assault,” said Boulder County District Attorney Michael Dougherty.

Dougherty said delays can also make it more difficult to prove a case because the defense can try to use it to raise doubts in jurors’ minds about the strength of the case or the impact the assault had on the victim.

“We then are in a position where we have to explain, to the extent we can, why it was so delayed in the charges being filed and then not being viewed as a reflection of the victim's credibility, but rather as a breakdown in the system with the state lab,” he said.

A long delay also makes it less likely a victim will want to move forward with the legal case and participate in the process.

“It's like, ‘I'm not getting answers, and the person who was my aggressor is still out there probably doing it to someone else.’ And that's when it becomes discouraging,” said Walezka Rivers, the sexual Assault Specialist with Advocate Safe House Project in Glenwood Springs.

She also noted that some victims may change their name and identity and move away for safety reasons. Without someone for prosecutors to work with, the case ends up closed.

Lawmakers offer money, try to reestablish deadlines

Currently, Colorado’s state lab has 16 DNA scientists, with another 15 in training. The goal is to have a full bench of 31 working by 2027.

And in February, the state gave CBI an additional $3 million to outsource the testing of 1,000 kits to external labs. With that additional help, CBI said it hopes to be through the backlog by the end of 2026. But it won’t be until 2027 that the turnaround times will really start to drop; CBI has set a goal of starting to process new kits within 90 days by that point.

“It's very much a resource issue,” said Democratic Sen. Mike Weissman of Aurora, who is leading efforts at the Capitol to try and speed up the process. He said more staff coming online is good news.

“The bad news is I don't think it's enough people soon enough to attack this problem as aggressively as most of us around here want to attack it.”

To head off future problems, Weissman is contemplating the state creating a coordinator position to help track everything.

Starting this summer people will also be able to track their individual sexual assault kit to see where it is in the process, as part of a law Colorado passed in 2023.

Even though there’s a concrete plan in place right now, there are still questions about CBI’s ability to carry it out.

“If all things stay the same except submissions go up, the backlog can grow. If we lose the capacity of the scientists to do the work, meaning someone resigns or leaves, then that decreases our capacity,” explained Lisa Yoshida, director of one of CBI’s regional forensic labs.

When it comes to how other places handle evidence testing, states have a variety of timelines for processing sexual assault kits. For instance, Connecticut, which employs a staff of 40 DNA scientists and has a population of about two-thirds of Colorado’s, gets kits processed within 30 days, according to research compiled by CBI.

“We start to feel very uncomfortable and concerned (about states) when that turnaround time gets above 90 days,” said Ilse Knecht, the policy and advocacy director for the Joyful Heart Foundation, a non-profit based in New York City that works with victims of sexual assault and domestic violence. Knecht directs their End The Backlog initiative.

The national scope of the issue isn’t clear, in part because the data isn’t compiled in a central location, although the Joyful Heart Foundation has information on some states and cities.

Knecht said a turnaround time of over 500 days — Colorado’s current pace — is pretty extreme. She said for places that are more than a year, “alarm bells are going off, so getting closer to almost two years is like a four-alarm fire.”

As for Spencer, as the wait stretches onward, she said she’s trying to be present for her 5-year-old daughter, who loves to dance and play with her stuffed animals.

“I need to move forward. I need to not be in this holding pattern. My whole life has stopped because of this,” she said.

“For my daughter, she's so young and it's just unfair to her that for a whole year and a half of her very short life, I have been consumed by this awful thing that happened to me.”

Spencer said it has helped to share her story, first with those closest to her and eventually with the public.

“I hope that more survivors can come together because I do think there's power in numbers. We have to stick together and I just hope that more women can find it within themselves to come forward and be uncomfortable. Because as uncomfortable as it is, it is very healing too.”

She got a temporary restraining order against the man from Bumble, but it’s expired, and she remains fearful of her alleged perpetrator, especially since he knows where she lives. Spencer said her attorneys have assured her she should be getting the results from her sexual assault kit soon. Yet, after all is said and done, she doesn’t know if she’ll ever get justice.

“I have learned throughout this whole process to not have any expectations.”

This story was produced by the Capitol News Alliance, a collaboration between KUNC News, Colorado Public Radio, Rocky Mountain PBS, and The Colorado Sun, and shared with Rocky Mountain Community Radio and other news organizations across the state. Funding for the Alliance is provided in part by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.