When artist and historian Chloé Duplessis first encountered the story of women washing twelve tablecloths a day at the Whitney Plantation in Louisiana, the experience left her silent.

"I couldn't shake it. I fell silent, and I just kept shaking my head and thinking how and why and all the things," Duplessis recalled in an interview with CPR. "I don't know what to do with this, but I have to do something."

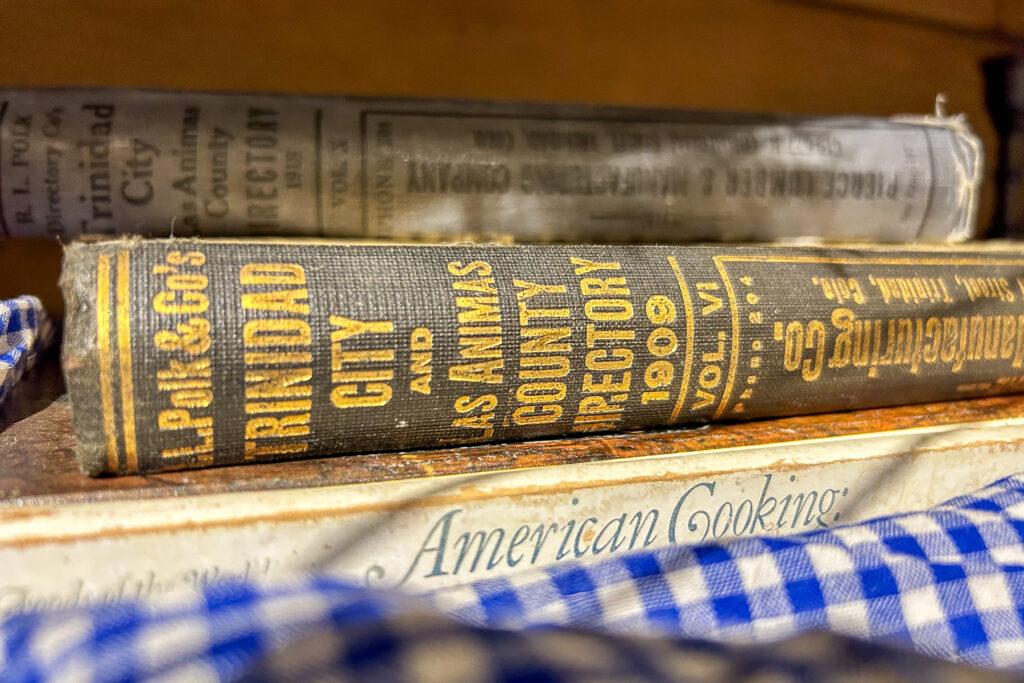

That moment stayed with her for years. It ultimately became the foundation for her traveling exhibition, Twelve Tablecloths. The installation, now at the Trinidad History Museum, honors the lives of Black domestic workers — women whose labor and stories were often unrecorded.

Duplessis, who is from Louisiana and now lives in Denver, had been doing historical research and producing art across the country. But it wasn’t until she completed an artist residency in Trinidad that she felt emotionally ready to bring Twelve Tablecloths to Colorado.

"It made sense for me because I actually lived here for almost a year and served here in the community," she said. "People tend to view enslavement as something that only happened in the South. But there were enslaved persons everywhere."

Naming the women

The installation in Trinidad features the stories of four Black women who worked as domestic servants in the town between 1890 and 1920: Birdie Gordon, Laura Graham, Margaret South, and Sophie Douglas. Duplessis discovered them through census records and was especially struck by Laura Graham. Early census records show her listed as Black, but about a decade later, she is listed as white.

"All the information is the same," she said. "And for people who study this work, we know that that means that Laura was passing."

Duplessis reflected on the emotional cost of racial passing: "You give up a portion of who you are. For this new identity, it’s required."

Textiles with meaning

Materials are essential to the storytelling of Twelve Tablecloths. One of the most prominent is burlap, a rough fiber Duplessis calls her "soul fabric."

"It represents the resilience and the capacity of Black women," she said. "When working with the burlap, I'm always reminded of all the ways in which Black women have had to contort themselves and bend and bow and present themselves to live, to survive."

Other symbolic materials include blue gingham, pinto beans, dried herbs and handspun ceramic plates created by artist Katie McWeeney. Each object and color was chosen with intention.

"We wanted to really give them their due," she said, referencing both the Black and Native women who worked in Trinidad. "Whatever you're preparing for the people on the main property, you're not eating. You're getting the scraps ... And I think that to a certain degree, every woman kind of has a little bit of that. We got a little bit of that awesomeness where we just know, ‘I'm gonna take what I have and make something extraordinary.’ It's our superpower.”

Accessibility as a value

Duplessis, who is legally blind and has a progressive eye condition, worked closely with museum staff to make the space accessible.

"It means walking into a space and being allowed to fully experience the work presented in a way that does not other me, in a way that does not require me to feel solemn or ask for permission," she said.

The exhibit uses colors designed for low-vision audiences and includes a seven-minute audio tour recorded by Duplessis herself.

"Twelve Tablecloths" is on view through August 8, 2025, at the Trinidad History Museum and will travel next to Fort Garland and Leadville.