Updated: Jan. 12, 2021

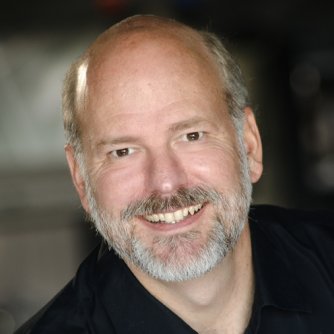

“Bach's cello suites have been my constant musical companions. For almost six decades, they have given me sustenance, comfort, and joy during times of stress, celebration, and loss,” Ma said as he announced his 2018 world tour. “Over the years, I came to believe that, in creating these works, Bach played the part of a musician-scientist, expressing precise observations about nature and human nature.”

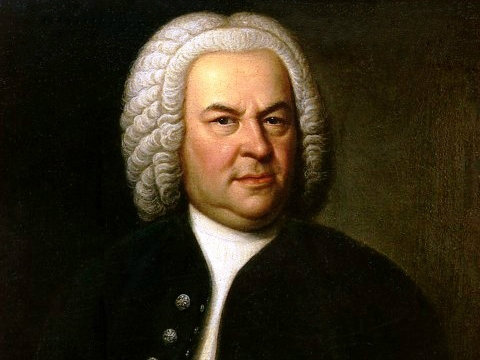

But Bach's six suites haven't always been so beloved or renowned.

The story of the Suites for Unaccompanied Cello is one of genius and tragic neglect, with a triumphant and long-lived epilogue. There is perhaps no other single set of compositions that have had more of a lasting impact in music history than the cello suites. But it took nearly two centuries for it to happen. Here's how it happened:

Luigi Boccherini was the only notable exception to the near-universal neglect of the cello as a solo instrument. Like other virtuosos, he wrote his own music, but very few others joined him. Joseph Haydn did write a couple concertos for a cellist in his orchestra, one of which was lost and not rediscovered until the 1950s. Virtually no unaccompanied works for cello were written in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Published, but still forgotten.

The suites were discovered and finally published in 1825. But in spite of their publication, they were not widely known by anyone besides a few cellists who viewed them as exercises -- if they viewed them at all. The development of the cello as a solo instrument continued without Bach's influence for another century, during which, again, virtually no music for solo cello was written.

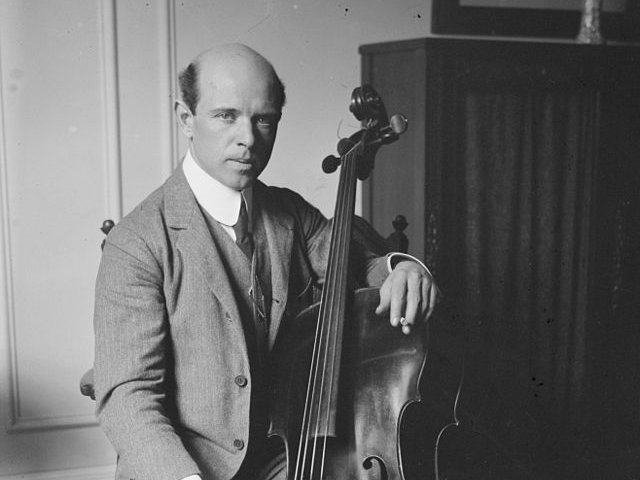

1889: The spark of discovery

A 13-year-old Catalan wunderkind cellist by the name of Pablo Casals went for a stroll with his father, and they stepped into a second-hand music shop. There, Casals stumbled upon an old copy of Bach's Cello Suites. He took them home, began to play them, and fell in love.

1915: Kodaly gets the hint

For the first time in almost two centuries, a major composer decided to write a work for unaccompanied cello. Zoltan Kodaly incorporated what is perhaps Bach's most radical technique in the cello suites -- scordatura (an alternate tuning of the strings) -- into a remarkably compelling sonata for solo cello. The same year, Max Reger wrote his own suites for unaccompanied cello, and the dam was broken.

The 20th century flood of cello music

Once Kodaly and Reger wrote their works, other composers jumped on the bandwagon. As a result, more music was written for unaccompanied cello in the 20th century than for any other solo instrument, save the piano.

1936: Casals records the suites

When Casals began recording the cello suites in 1936, the ground shifted under the endpins of all cellists. Suddenly there was an expectation that every cellist should know the suites, and indeed no true virtuoso of the cello could be legitimate without actually producing a recording of them. The number of recordings of the suites exploded, as did their popularity and influence.

What makes the suites so powerful?

It took more than 200 years for the world to get to know these miraculous suites. But once they become known, they became one of the most influential works ever written. A century later, composers are still writing works based on them. Cellists are still plumbing their depth. Why?

It could be said that if the cello were to write music for itself, it would be the Bach cello suites. No other work for solo cello is as broadly expressive, as widely varied, or as native to the instrument itself as Bach's suites.

Being the master he was, Bach deeply considered the instrument, and then wrote the music it should play. Centuries later, the suites remain the ultimate expression of the soul of the cello, given voice by superstars like Yo-Yo Ma and countless other cellists who study, play and cherish them.

Hear Bach every weekday at 5 p.m. Listen to CPR Classical by clicking “Listen Live” on this website, tuning in to 88.1 FM in Denver, at radio signals around Colorado, or ask your smart speaker to “Play CPR Classical.”