Diabetic ketoacidosis is a terrible way to die. It's what happens when you don't have enough insulin. Your blood sugar gets so high that your blood becomes highly acidic, your cells dehydrate, and your body stops functioning.

Diabetic ketoacidosis is how Nicole Smith-Holt lost her son. Three days before his payday. Because he couldn't afford his insulin.

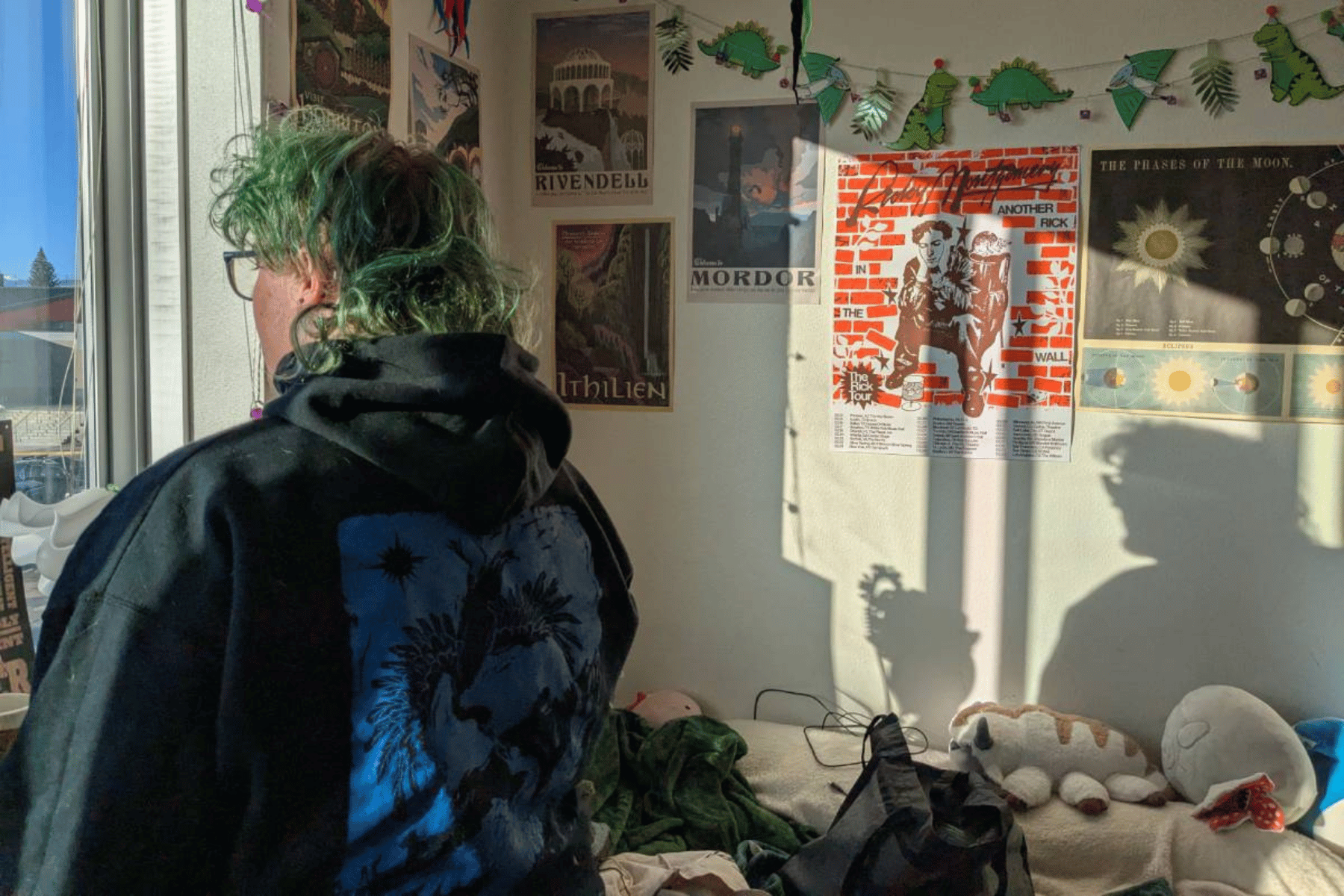

"It shouldn't have happened," Smith-Holt says looking at her son's death certificate on her dining room table in Richfield, Minn. "That cause of death of diabetic ketoacidosis should have never happened."

The price of insulin in the U.S. has more than doubled since 2012. That has put the life-saving hormone out of reach for some people with diabetes, like Smith-Holt's son Alec Raeshawn Smith. It has left others scrambling for solutions to afford the one thing they need to live. I'm one of those scrambling.

Not enough time

Most people's bodies create insulin, which regulates the amount of sugar in the blood. In the U.S., the roughly 1.25 million of us with Type 1 diabetes have to buy insulin at a pharmacy because our pancreases stopped producing it.

My first vial of insulin cost $24.56 in 2011, after insurance. Seven years later, I pay more than $80. That's nothing compared with what Alec was up against when he turned 26 and aged off his mother's insurance plan.

Smith-Holt says she and Alec started reviewing his options in February 2017, three months before his birthday on May 20. Alec's pharmacist told him his diabetes supplies would cost $1,300 a month without insurance — most of that for insulin. His options with insurance weren't much better.

Alec's yearly salary as a restaurant manager was about $35,000. Too high to qualify for Medicaid and, Smith-Holt says, too high to qualify for subsidies in Minnesota's health insurance marketplace. The plan they found had a $450 premium each month and an annual deductible of $7,600.

"At first, he didn't realize what a deductible was," Smith-Holt says. She says Alec figured he could pick up a part-time job to help cover the $450 per month.

Then Smith-Holt explained it.

"You have to pay the $7,600 out of pocket before your insurance is even going to kick in," she remembers telling him. Alec decided going uninsured would be more manageable. Although there might have been cheaper alternatives for his insulin supply that Alec could have worked out with his doctor, he never made it that far.

He died less than one month after going off of his mother's insurance. His family thinks he was rationing his insulin — using less than he needed — to try to make it last until he could afford to buy more. He died alone in his apartment three days before payday. The insulin pen he used to give himself shots was empty.

"It's just not even enough time to really test whether [going without insurance] was working or not," Smith-Holt says.

A miracle discovery

Insulin is an unlikely symbol of America's problem with rising prescription costs.

Before the early 1920s, Type 1 diabetes was a death sentence for patients. Then, researchers at the University of Toronto — notably Frederick Banting, Charles Best and J.J.R. Macleod — discovered a method of extracting and purifying insulin that could be used to treat the condition. Banting and Macleod were awarded a Nobel Prize for the discovery in 1923.

For patients, it was nothing short of a miracle. The patent for the discovery was sold to the University of Toronto for only $1 so that live-saving insulin would be available to everyone who needed it.

Today, however, the list price for a single vial of insulin is more than $250. Most patients use two to four vials per month (I personally use two). Without insurance or other forms of medical assistance, those prices can get out of hand quickly, as they did for Alec.

Depending on whom you ask, you'll get a different response for why insulin prices have risen so high. Some blame middlemen — such as pharmacy benefit managers, like Express Scripts and CVS Health — for negotiating lower prices with pharmaceutical companies without passing savings on to customers. Others say patents on incremental changes to insulin have kept cheaper generic versions out of the market.

For Nicole Holt-Smith, as well as a growing number of online activists who tweet under the hashtag #insulin4all, much of the blame should fall on the three main manufacturers of insulin today: Sanofi of France, Novo Nordisk of Denmark and Eli Lilly and Co. in the U.S.

The three companies are being sued in the U.S. federal court by diabetic patients in Massachusetts who allege the prices are rising at the expense of patients' health.

The Eli Lilly did not make anyone available for an interview for this story. But a company spokesman noted in an email that high-deductible health insurance plans — like the one Alec found — are exposing more patients to higher prices. In August, Eli Lilly opened a help line that patients can call for assistance in finding discounted or even free insulin.

A dangerous solution

Rationing insulin, as Nicole Smith-Holt's son Alec did, is a dangerous solution. Still, 1 in 4 people with diabetes admits to having done it. I've done it. Actually, there's a lot of Alec's story that feels familiar to me.

We were both born and raised in the Midwest, just two states apart. We were both diagnosed at age 23 — pretty old to develop a condition that used to be called "juvenile diabetes." I even used to use the same sort of insulin pens that Alec was using when he died. They're more expensive, but they make management a lot easier.

"My story is not so different from what I hear from other families," Smith-Holt recently told a panel of U.S. Senate Democrats in Washington D.C., in a hearing on the high price of prescription drugs.

"Young adults are dropping out of college," she told the lawmakers. "They're getting married just to have insurance or not getting married to the love of their lives because they'll lose their state-funded insurance."

I can relate to that, too. My fiancé moved to a different state recently, and soon I'll be joining her. I'll be freelancing and won't have health benefits, though she will via her job. We're getting married — one year before our actual wedding — so I can get insured, too.

This story is part of NPR's reporting partnership with Side Effects Public Media and Kaiser Health News. A version of this story appears in The Workaround podcast.

9(MDEyMDcxNjYwMDEzNzc2MTQzNDNiY2I3ZA004))