Saving African wild cats, elephants and other species from extinction takes serious police work. That’s why some of the continent's conservation officers came to Commerce City, Colorado.

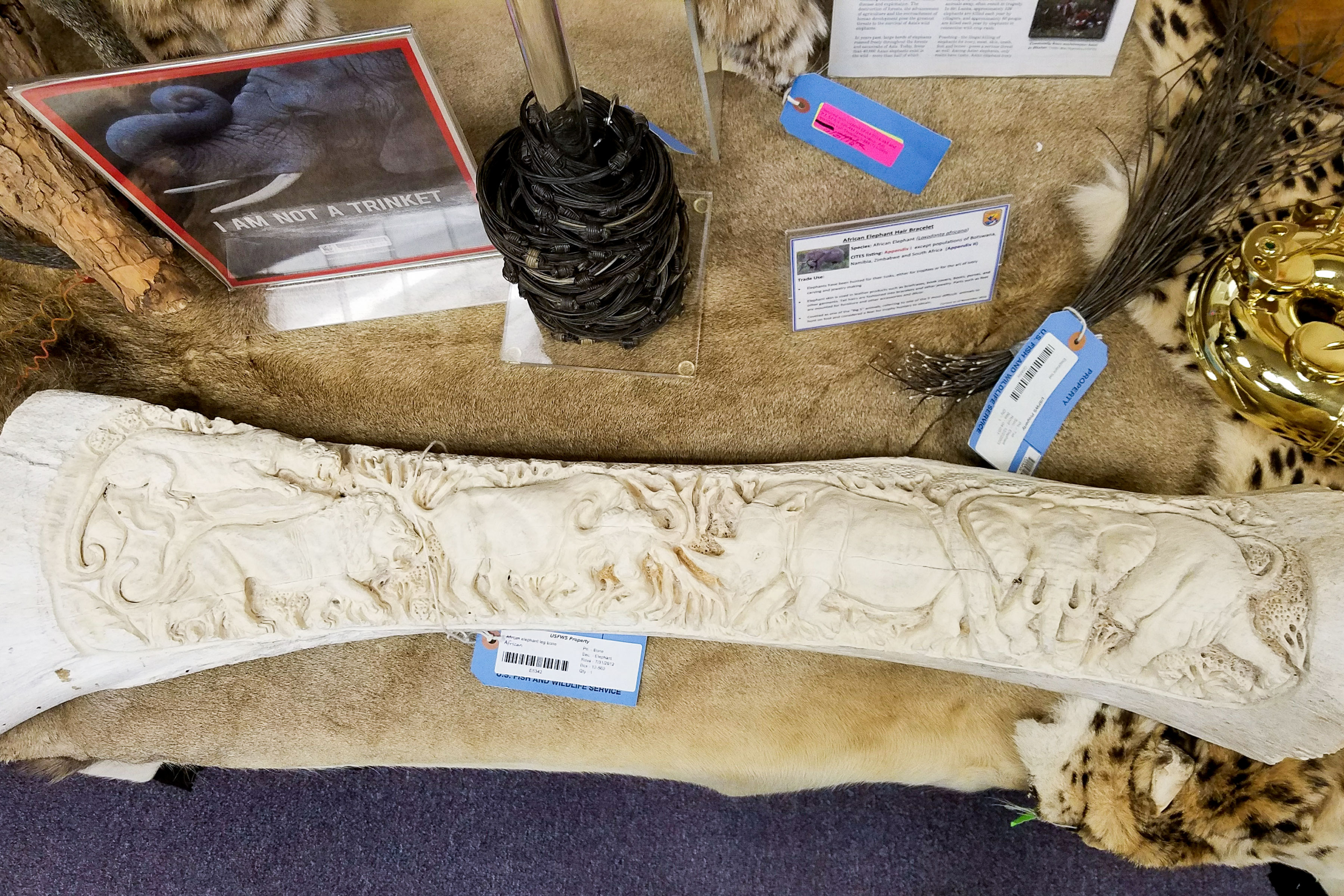

They came to train with their U.S. counterparts at a sort of mausoleum for animals lost to poachers and wildlife traffickers: the National Wildlife Property Repository.

Coleen Schaefer, a specialist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, led the delegation of 42 conservation officials through the warehouse. She held up a business card holder fashioned from an elephant toenail.

The object is one of 1.3 million at the repository. There's also skin lotion made with caviar and pencil holders made from baby rhino feet.

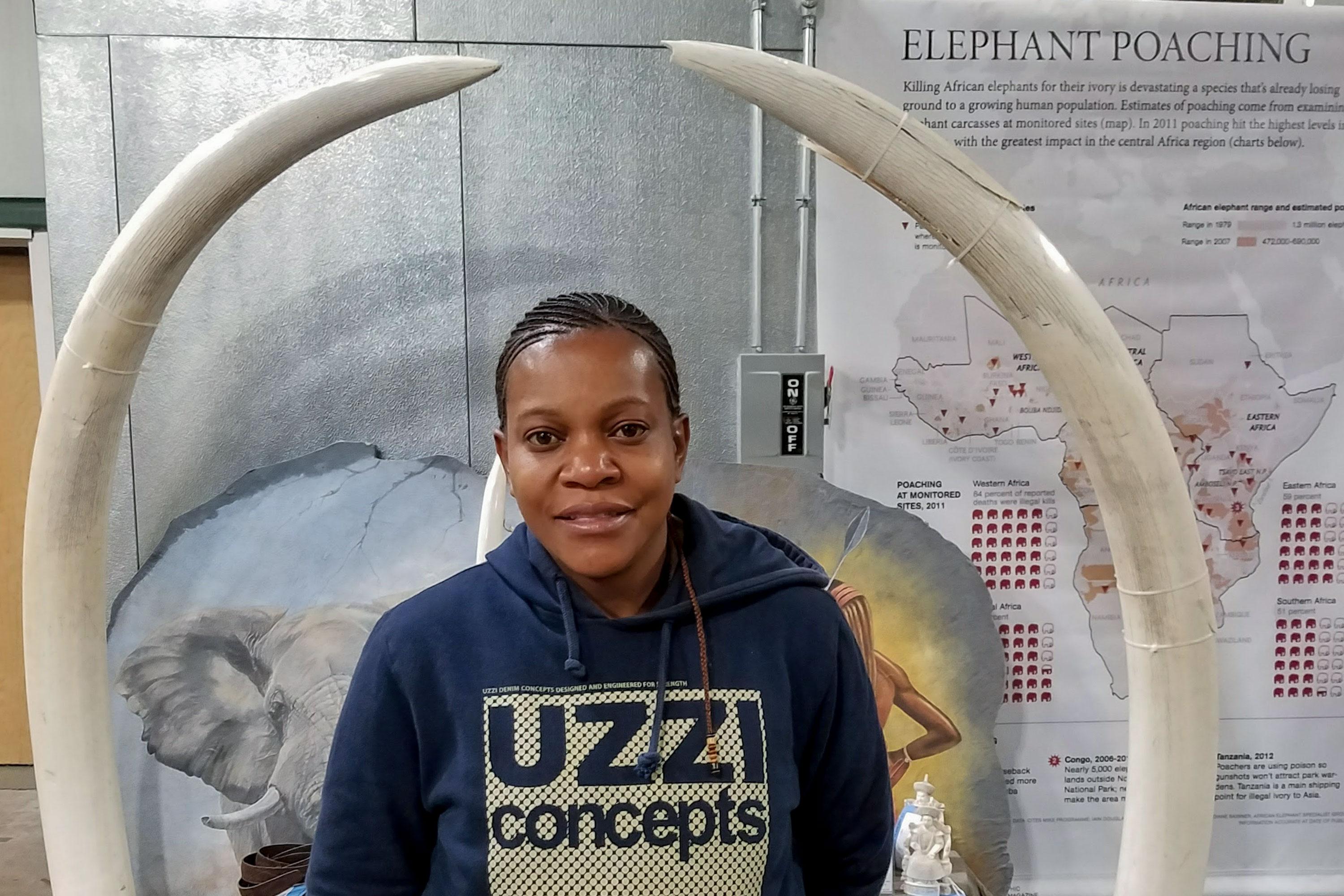

“It makes me feel bad,” said Georgina Kamanga, the lead intelligence officer for the Zambian Department of National Parks and Wildlife. She looked through a box of elephant skin wallets and accessories. “The products are just too much.”

Kamanga recently gained a bit of international fame. She appears in “The Ivory Game,” a Netflix documentary centered on international ivory smuggler Boniface Matthew Maliango. In the film, Kamanga leads a raid against one of his syndicates.

In 2016, a Tanzanian court sentenced Maliango to 12 years in prison for poaching crimes. Kamanga said success had a lot to do with what happened after the excitement of the raid: regular, mundane police work.

“Evidence was secured. It was properly labeled. Everything went according to plan,” she said.

That kind of attention to detail is important according to Dave Hubbard, who oversees U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service agents who work abroad. He said the value of the products can be a temptation for law enforcement officers with low pay.

“The seized wildlife, through corruption or other means, can go out the back door and there's no accountability for it,” he said.

During the training at the repository, USFWS IT specialist Mike McCloud led the delegation through techniques to keep evidence secure and carefully cataloged.

“So I have this lovely handbag,” he said of a tiger print purse made from stingray skin. He assigns it a barcode, takes a photo and then enters all the information into a laptop.

Even though the process seems high-tech, McCloud said it doesn't need to be. A notebook can be a database. He also recommended regular checks to make sure no evidence has gone missing.

“The best evidence handling, even the best lab analysis — if it's not documented properly, consistently, easily retrievable it's worthless,” he said.

Zambian wildlife officer Kamanga said she'll take that tip to heart.

“I have to be sure that when I go back home I share this with other colleagues I work with,” she said.

In the repository, Kamanga saw proof of both the size of the wildlife trafficking problem and the international commitment to fighting it.

“What has been detected is more like a tip of an iceberg,” she said. “There is more and we need to collaborate further and work so hard to make sure these poachers are nailed before they cross borders.”

As the U.S. Fish and Wildlife attache for Southern Africa, nailing poachers is Ed Newcomer's job. He said the repository is a teaching lab, but it should be seen for what it is: “a collection of some of the most iconic species in the world that are no longer living. You will not have an opportunity to see those elephants or those tigers or those lions ever again because now they are in a warehouse in Colorado.”