Business as usual on the Colorado River may be about to come to a screeching halt.

One of the worst recorded droughts in human history has stretched water supplies thin across the far-reaching river basin, which serves 40 million people.

Nowhere is this more obvious than Lake Mead, which straddles the border of Arizona and Nevada. The water level in the country’s largest manmade reservoir has been plummeting; it’s now only 37 percent full.

With an official water shortage imminent, Arizona, Nevada and California are taking matters into their own hands. The states are hammering out a voluntary agreement to cut their water use -- an approach some consider revolutionary after so many decades of fighting and lawsuits.

The cooperation springs from self-preservation. If Lake Mead drops too low, the federal government could step in and reallocate the water.

At the same time, upper basin states like Colorado and Wyoming want to use more Colorado River water -- something they’re legally entitled to.

In Colorado, Denver Water is in the final stages of seeking approval on a water storage project that would take more water out of the Colorado River. Wyoming is researching whether to store more water from the Green River, a Colorado tributary. Utah is discussing whether to build a pipeline to transport water from Lake Powell, the reservoir found up river from Lake Mead along the Utah - Arizona border.

Add in the likely impacts of climate change and how it’s affecting the Colorado River basin and you have an increasingly complex and challenging picture developing for the 21st century.

Pat Mulroy, a senior fellow at the William S. Boyd School of Law at the University of Nevada Las Vegas and a leading Western water expert, says the time for a new toolbox and ideas to approach water management has arrived.

“There won’t be any winners and losers,” Mulroy says, unless Colorado River states move beyond the fighting and lawsuits of the last century as they try to adapt to the next century. “There will only be losers.”

Upper Basin States Want More Storage

There’s a silent miracle that delivers water every day to Denver Water’s 1.4 million customers. For decades, the Fraser River, a tributary of the Colorado River, has flowed through a manmade system of dams, diversions and tunnels beneath the Continental Divide.

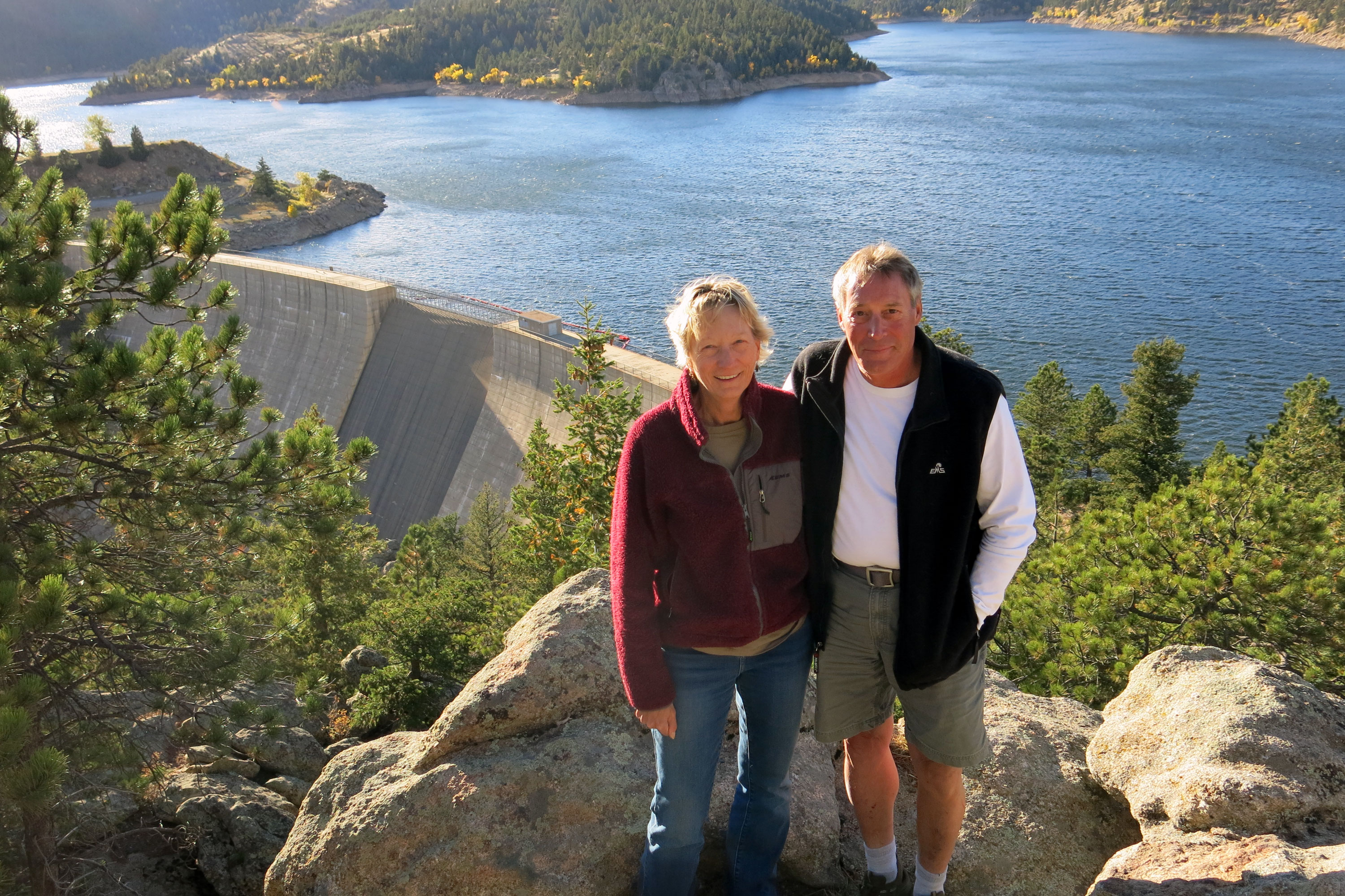

A critical linchpin sits just outside Boulder. Gross Reservoir is a man-made lake that provides reliable storage for Denver Water. Retired IBM workers Beverly Kurtz and Tim Guenthner live just out of eyesight from the reservoir. For Kurtz, that’s on purpose.

“It’s choking off a wild river which in my opinion is never a good thing,” Kurtz says.

The couple have a new-found job in retirement. It’s fighting a proposed expansion to Gross Reservoir’s dam. Denver Water wants to raise the dam by 131 feet.

“It doesn’t make sense to build a multi-million dollar dam and disrupt the environment here, when down the line,” Kurtz says, “that’s not going to solve the problem.”

The problem is that Colorado’s population is expected to nearly double by 2050. A carefully crafted water plan by Colorado’s top chiefs calls for 400,000 more acre feet of storage, and 400,000 additional acre feet of conservation.

Denver Water CEO Jim Lochhead says more storage is an important part of the solution. It’s also an insurance policy against future drought.

“From Denver Water’s perspective, if we can’t provide clean, reliable, sustainable water 100 years from now to our customers, we’re not doing our jobs,” Lochhead says.

With the proposed expansion of Gross Reservoir, Denver Water took a new approach. The agency worked with environmental groups and Western Slope water interests on the Colorado River Cooperative Agreement. Part of the effort involves Denver Water actively working on the Fraser River to narrow the stream channel and restore the river. If the agency gets the green light to expand Gross, it would be required to keep a formal relationship with environmental groups and local governments through the life of the project.

But that expansion is still expected to decrease stream flows by about one half of what they are now.

In Wyoming, state engineer Pat Tyrrell says the state is studying whether to store more water from the Green River, another Colorado River tributary.

“We feel we have some room to grow. But we understand that growth comes with risk,” he says.

There’s risk because Wyoming could expand reservoirs with proper permits. In 10 or 20 years there may not be enough water to fill that storage -- or deliver enough water to existing reservoirs like Lake Powell. Upper basin states have developed a contingency plan to make sure that happens in the future.

Imbalance Between Supply and Demand

What unites all water planners from Colorado down to California is the need for certainty. They need confidence there will be enough water to fuel population and agricultural growth. And there’s a huge new wildcard in the deck.

“Climate change upsets all aspects of the water cycle,” says Brad Udall, Senior Water and Climate Scientist at the Colorado Water Institute at Colorado State University. He says hotter temperatures and drought make certainty a thing of the past.

Udall says a 16-year drought has dramatically decreased water supply. This recent past could be indicative of what the future holds. He worries that flows across the basin could be reduced by as much as 20 percent by 2050.

“We know that temperatures are going to go up,” Udall says. “We know the temperature increases will influence the river flows, and that influence is likely to be strongly downward.”

Right now users along the Colorado River face a critical juncture. Deputy Secretary of the Interior Michael Connor recognizes the stress that climate change could have on future water supply. He also understands how over-allocated the river is now.

“The imbalance between supply and demand, is just going to increase over the next 50 years if we don’t have some very strategic plans that we put in place,” Connor says.

Lower Basin States Turn To Cooperation

Downstream, the imbalance between supply and demand is already a reality. With an historic water shortage on the horizon, California, Arizona and Nevada are working on a voluntary agreement to cut back water use.

The stakes are especially high in California, where Colorado River water has played a critical role in the state’s five year drought.

“It’s been the reliable source of water for us,” says Jeffrey Kightlinger, manager of the Metropolitan Water District, a water wholesaler that serves 19 million people in Southern California, and major power player in California water policy. “We’ve been getting hardly anything from Northern California.”

At least a quarter of Metropolitan’s water supply comes from the Colorado River, which is delivered through a 240-mile aqueduct that stretches to the Arizona border.

That supply is reaching a crisis point. Lake Mead could drop so low in 2017, an unprecedented shortage could be declared.

“That’ll be a historic moment,” Kightlinger says.

Arizona and Nevada would be forced to cut back on how much water they draw from the river. California wouldn’t be required to, because it has senior water rights. But if levels in Lake Mead keep dropping, the federal government could step in and reallocate the water, including California’s share.

In a last-ditch effort to avoid that, the three states are hashing out a voluntary agreement. Arizona and Nevada are considering deeper water cuts, if California agrees to cuts amounting to somewhere between five and eight percent of its supply.

“We all realize if we model the future and we build in climate change, we could be in a world of hurt if we do nothing,” says Kightlinger.

These negotiations would have been unthinkable just a decade ago, Kightlinger says. The three states have years of bad blood among them over the river. Most disagreements have been settled with lawsuits.

For some, that’s not easy to forget.

“We know there’s a target on our back in Imperial Valley for the amount of water we use,” says farmer Steve Benson, checking on one of his alfalfa fields near the Mexican border.

The valley produces two-thirds of the country’s vegetables in the winter. Its sole source of water is the Colorado River. Benson sees little reason to share it because the district has senior water rights that trump the rights of Metropolitan Water District.

“Other districts need to understand their place and their rights,” he says.

Many farmers also say they’ve compromised enough already.

For decades, California used more than its legal share of the Colorado River and finally agreed to cut back in 2003. The Imperial Irrigation District was under pressure to transfer water to cities like San Diego to make the cutbacks possible.

“It was the single, hardest decision I have ever made in my life,” says Bruce Kuhn, who voted on the water transfer as a board member of the district. He cast the deciding vote to share the water, but it came at a personal price.

“It cost me some friends,” he reflects, still sighing at the memory. “I mean, we still talk but it isn’t the same.”

Kuhn may have to make that same call again, and soon. California’s plan to voluntarily give up water to avoid an emergency shortage will likely come up for a vote. The Imperial Irrigation District is considering the deal, but is looking for incentives like the ability to bank water in Lake Mead.

Jeffrey Kightlinger of the Metropolitan Water District says it’s a tough conversation. “But if the Colorado River dries up, Imperial goes out of business. It’s in all our interest to solve this.”

To some, the negotiations are sign of what’s to come on an increasingly-stressed river.

“Can we get through?” asks UNLV’s Pat Mulroy. “Yes, but not the same way we got through the last 100 years. There’s a different set of interconnections and relationships that have to be forged. So it’s how we tackle the problem that has to change.”