Feeling like a Martian.

Having a black hole of information where your origin story should be.

Being grateful for your loving adopted family, but still feeling lost.

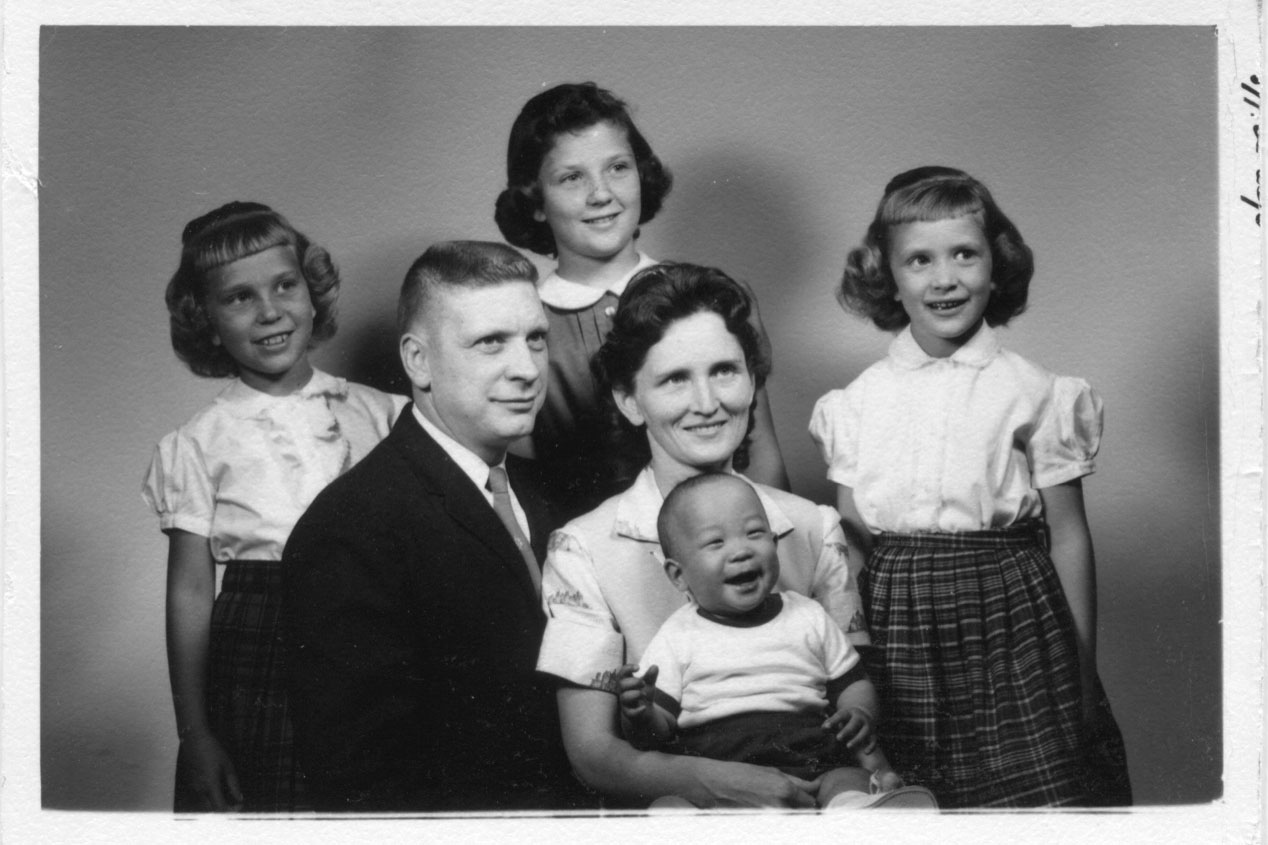

These are the common threads in the stories Glenn Morey heard from South Korean children who were adopted into white families. The Denver filmmaker was a Korean adoptee himself, and set out to record his interviews with other transracial adoptees in his project, "Side by Side: Out of a South Korean Orphanage and Into the World."

Even if the adoptees were too young to have memories of being separated from their lives in South Korea, and even if they land in loving families, the complicated feelings surrounding race and adoption still arise.

Interview Highlights

On the media and pop culture portrayal of Korean adoptions:

"At that time, adopting from another country was certainly a more expeditious way to form a family. I think that it was also seen, and certainly positioned in the media, as an act of humanitarian rescue. There was a picture created by the media of these children, this was in many cases a true picture, of these children and babies in orphanages in dire need of a home and certainly at risk. In fact, the orphanage I came out of had a 25 percent mortality rate."

On never really knowing your origin story:

"It’s not uncommon to be completely without information. I have a file, but there’s really nothing in it that could help me determine the story of my origin. There was no note attached to me, there was not information attached to me. I was simply abandoned in Seoul and left to be processed through City Hall to what orphanage, to whatever orphanage could take me."

On the unchanging attitudes of race and feeling like "a Martian":

"This was almost an entirely typical story that we heard. Most adoptees were adopted into families that were white, so transracially adopted. Most of them were adopted into communities that were predominantly or entirely white. And in many cases, rural. So, this is not uncommon.

While I wish I could say that this story was limited to those of us who were adopted during the 60s or even the 70s, it’s really not the case. Having interviewed people born all the way from the 50s to the 90s, this story barely changed. I think the biggest reason it didn't change is there are attitudes about race in our society that continue to today. Like, ‘Race isn’t important,’ ‘We’re all colorblind,’ ‘I don’t see you as Korean, I don’t see you as being of a different race.’

Which might sound in some way socially right, but the truth is these adoptive children often took this information to mean that nobody wanted to talk about their race, that in fact they weren’t supposed to talk about their race, and that to acknowledge race even was somehow wrong or shameful."

On being grateful for having a loving adoptive family, but still feeling confused:

"Most of the people we talked to were raised in loving homes. But that’s not the determining factor on how people feel about their origins. You can be happy about your upbringing and where you are today in life, and still be sad about the fact that your origin is either a black hole of information, or your origin is somehow disturbing. It’s possible, I believe, to be a happy person, grateful person, thankful person for your circumstances, but at the same time, to have very, very complicated feelings about the way that you came into the world."