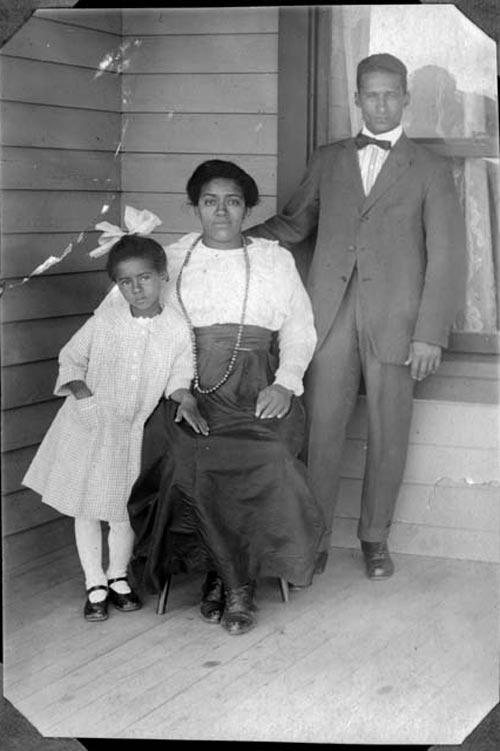

A “spitfire” of a little girl, Marie Greenwood craved adventure. That spirit and tenacity helped her overcome racial barriers to become the city’s first black tenured teacher. It’s a journey that started in the halls of Denver’s Morey Middle School.

That was also 92 years ago. Today, it’s her first time back since graduation.

When Marie Greenwood arrives at the Capitol Hill neighborhood school, principal Noah Tonk greets her gently, with a little joke, asking if she’s returning a library book. It’d be a pretty hefty fine.

“I was born in 1912,” she says. “So all you got to do is make this subtraction…”

The math works out to 105-years-old with a birthday later in November. Her eyes are bright and expressive; her words sharp, witty, and warm — it’s a good bet that Marie Greenwood was this way on her first day through the doors at Morey.

With an unwavering belief that every child can learn, Greenwood has a long and storied history as a Denver teacher who broke down racial barriers. She wrote a book, “Every Child Can Learn,” with tales of challenges and triumphs with students known as “Big Girl Dora,” “Attentive Betty,” “Belligerent Marilyn” and “Stubborn Mattie.”

There’s a K-8 school named in her honor, Marie L. Greenwood Academy, in northeast Denver. Each year, fifth- and-sixth graders there read her autobiography, “By the Grace of God,” which she completed at age 100. The students then lead lessons on her story for third-grade students and create a game of Jeopardy about facts from her life.

She loves Jeopardy.

“I get a big kick out of it if I know the answer, and if I don't, then I learn something new," she says. It’s a testament to her pride in being a lifelong learner.

Being a centenarian hasn’t cramped Marie Greenwood’s style. She continues to participate in Each One Teach One, an early literacy program. As they do with her biography, Each One Teach One students later pass their new knowledge to younger Greenwood Academy classmates. An education nonprofit, Friends of Marie L. Greenwood, has also just been formed.

“This is so good you get to come back mom!” Greenwood’s son James says as he rolls her wheelchair into the old gym at Morey. Her face lights up. The gears of memory aren’t slow cranking. Greenwood goes back instantly to the young girl in a wool skirt, leggings, a white shirt and tie — a typical gym outfit for 1925.

“They had ropes that came down, I could really climb those ropes faster than anybody! However, I made the mistake once of sliding down with my hands. I don’t think my hands would ever stop hurting!” she laughs.

Greenwood’s world opened up through sports, she felt it was the one place where she was absolutely free. “In the classrooms it was another story, because there was that feeling of discrimination,” she says, but gym was something else. Morey school had a pool, so she taught herself how to swim from library books and practiced breathing underwater in the sink at home.

But even in the gym, the realities of that time in American history couldn’t be escaped. As an African-American, she couldn’t swim in the pool.

“Well, to tell the truth, it never dawned on me much that I was a different color because my father had always taught me I was as good as anybody else and if I worked hard enough I could be better,” she said. “And I had that attitude even though I ran into this discrimination.”

The incident spurred her on. “It got me out of some of that shyness and made me say, ‘I’m going to prove that I can be the best,’ and from then on, that’s what I did.”

She later met a group of black girls during an assembly. There weren’t many at the time. Up until that point, Greenwood would have described herself as a loner. Those girls would become her support network, several staying friends for the next 70 years.

Greenwood also reminisces about discriminatory behavior from a social studies teacher who liked to embarrass her when she didn’t know an answer and never called on her when she did. Greenwood outsmarted her.

“I could look stupid as could be,” when she knew the answer and the teacher would call on her. Conversely, she would wave her hand when she had no idea what was going on.

“You know that's when she’d ignore me,” Greenwood says of her ruse. “Oh, I learned the greatest technique of how I could look ... she got confused too!”

She fondly remembers others, like the math teacher who helped her after school until she finally “got it.” From there, Greenwood began excelling. The teacher gave her a compliment she remembers to this day.

“He told me I had a mathematical mind.”

Greenwood also had a temper. As she writes in her autobiography, “I was not afraid of anybody or anything and would say or do whatever came to mind in retaliation against whoever had offended me.”

Push her too far and she’d just explode, Greenwood says. Her home economics teacher taught her to think and wait before exploding or just leave the situation. While Morey gave Greenwood many fond experiences, in high school she encountered more racism.

At Denver’s East High School, she wasn’t allowed to play sports or join clubs. An administrator told her to not bother with college because she’d just be cleaning houses. Greenwood replied that she was going to college. Then she went into the bathroom and cried. She scrunches her eyes and balls up her fists at the memory.

“I pounded the walls and said I’m going to show them!”

And she did. Fortunately, her family moved across town and she enrolled at West High, where the principal didn’t tolerate discrimination. She calls her move to the school off of 9th and Galapago her salvation.

Graduating third in her class, Greenwood won a scholarship and went on to teacher’s college. In 1935, Denver Public Schools hired her as a first grade teacher at Whittier Elementary School for $1,200 a year. Three years later, she was the first teacher of color to get tenure.

Greenwood had two goals from then on. The first was to “keep that job” and the other was to “keep the door open for others to come in.”

Later, Marie Greenwood became the first black teacher in an all-white school. From there it was a very Colorado life: she raised a family, skied a lot, and camped all over the West. To her son, James, they were just another family in Denver.

“Mom and Dad were just mom and dad,” he says. “We didn't realize that they had not only been through what they had been through, but had achieved what they had — ‘cause to us that was just normal.”

James remembers the family growing up as “total and complete adventurers,” which he attributes to his mother’s never say no attitude. Instead, Marie Greenwood would ask, “how are you going to do it?” It’s that attitude she carried into the love of her life: teaching. And it’s a love she loves to talk about.

“Well, you see, get me wound up by like the Energizer bunny, I just go on and on and on and on and on,” she says with her characteristic wit.

Greenwood thinks of education like building a good house. It all starts with the foundation. In the classroom, that foundation is first grade. Just like her start at Morey Middle School. You’d expect nothing less from a 105-year-old who devoted 30 years to teaching first grade.

“At my age, I'm amazed that I can still walk and talk and breathe and know what's going on and come back to the first school in Denver that I ever attended,” Greenwood says. “I'm blessed that I've been able to do it.”