Published 6:35 a.m. | Updated 7:50 a.m.

As the hours of bargaining between the Denver Classroom Teachers Association and Denver Public Schools dragged on, the Wednesday session became a Thursday one. Shortly after 5 a.m. bleary-eyed and tired negotiators returned to the room.

“This is a comprehensive proposal that will… We think it will end the strike,” said lead negotiator Rob Gould.

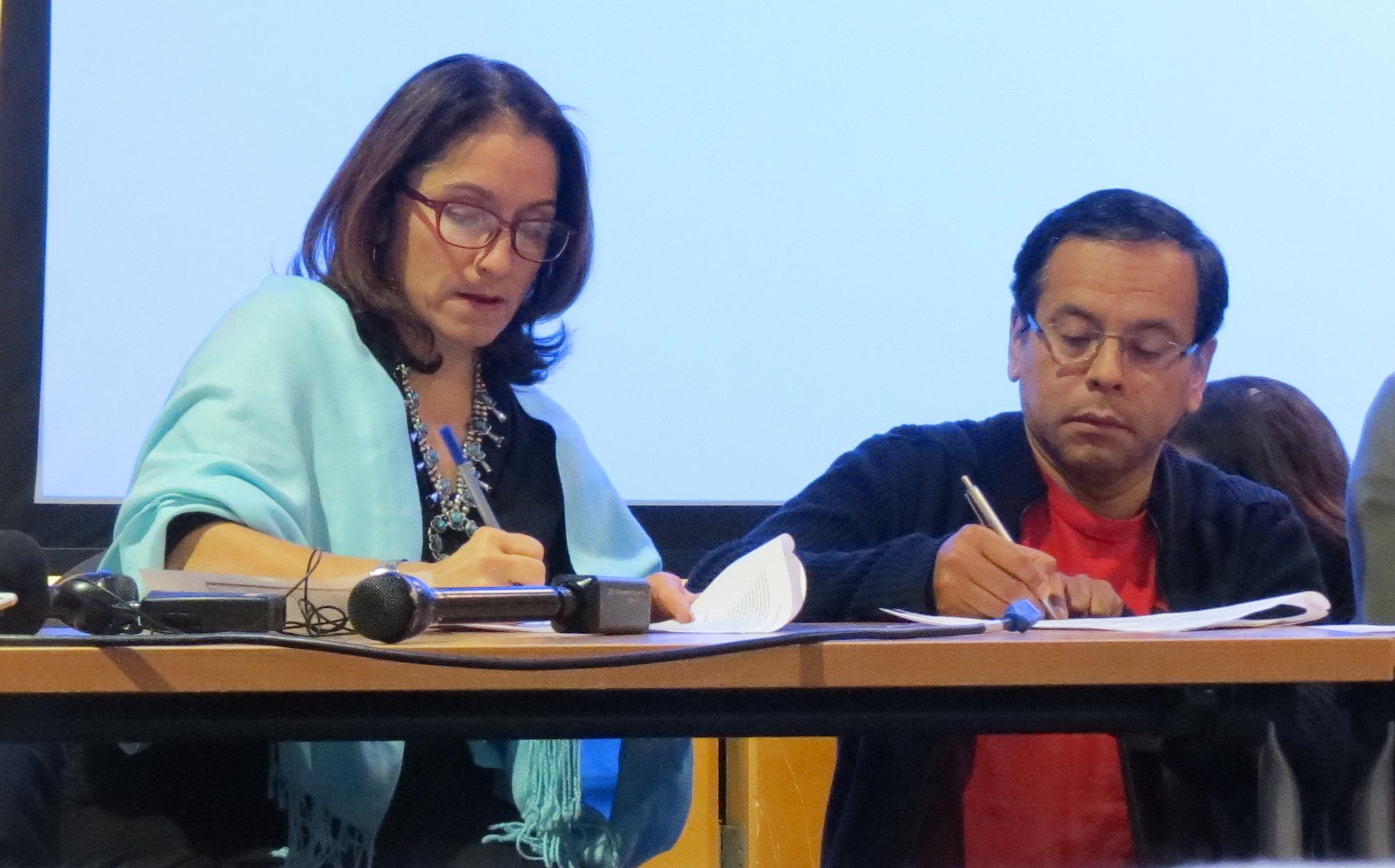

In the end they were right. Superintendent Susana Cordova accepted the tentative deal after she recommended one change: “We’d like to add a signature line to the proposal.” After the deal was signed by Cordova and union president Henry Roman, Gould recommend to membership that the strike be ended.

It's an unpaid day if they don't go back today.

Gould: Teachers may return to work today if they want today. If they don't, it's an unpaid day. Today's it's a historic day. Educator in Denver Public Schools have a fair predictable and transparent salary structure.

The all-nighter, which eclipsed the record set in 1994 for the longest bargaining session, hammered out the details between teachers and the district. The union’s offer agreed to $3,000 retention bonus for high priority schools — with the caveat that study be conducted on their effectiveness — $2,000 incentive for hard to fill and hard to staff schools, and a salary structure that starts at $45,800 with seven lanes and 20 steps for pay advancement. Teachers can use professional development units as credits towards salary advancement and here’s potential to move to a salary of $100,000 with a doctorate.

The deal puts $25.2 million more into base salary, slightly lower than the union’s original ask of $28.5 million. In exchange, the union signed off on the contentious bonuses for high priority schools. Other than the salary structure and professional development to change pay lanes, the incentives had been one of the biggest sticking points in negotiations.

District officials say on average teachers will have and 11.5 percent raise next year. Union officials say they’re still crunching those numbers.

Cordova, before the district ducked into a quick caucus to review the offer, told the assembled members of the DCTA that she appreciated the “time and the effort and the energy” invested.

“There was a lot of compromise, I think on both of our parts, to get to a point where we’re maybe this close away from being able to sign on some dotted lines,” she said.

After three days of demonstrations, negotiations between Denver Public Schools and the Denver Teachers Classroom Association began to thaw — which led to the marathon session and the breakthrough.

For teacher Paula Zendle, the strike overall felt like a marathon, one that was “physically exhausting and definitely emotionally draining.” The former accountant, spent hours analyzing pay schedules with each new proposal. She was on the picket line every day, driven by a desire to be compensated similarly to other districts.

“It was, it’s a good thing to go through, but I wouldn’t want to go through it again if I don’t have to,” she said with a laugh. “I definitely don’t want to go through that again if I don’t have to.”

Teachers say the strike was the result of years of frustration over a pay and compensation system they contend was broken. Denver voters enshrined a tax to fund the ProComp system in 2005. Teachers felt the system didn’t provide predictable pay and questioned whether the bonuses accomplished their stated goals.

When the contract expired in January, teachers voted overwhelmingly to strike shortly after. Denver Public School asked for the state to intervene, which delayed the start of the strike. After Gov. Jared Polis declined to get involved and a late bargaining session failed to reach a resolution, teachers officially went on strike. Since Monday, more than half of teachers didn’t report for work and instead picketed on frigid early mornings, often joined by high school students who walked out of classes.

After the relief of the finished bargaining session and with signatures on the tentative deal, DCTA lead negotiator Rob Gould said their goal was to “make sure that we had a fair and comparable salary structure to other districts. And we’re excited that we were able to do that.”

“It’s a victory for Denver’s kids and it’s a victory for our parents and our and our teachers and we’re excited that we’ll be able to get back to work,” Gould said.

Cordova was happy to welcome teachers back to school and acknowledged that for many, the news of the tentative agreement may have reached them too late and some may not have lesson plans. Teachers who don’t make it into school at this late hour will take an unpaid day.

“I have heard from so many parents and children that they want their teachers back,” she said. “And I do too and so we’re really looking forward to being able to have them back.”

Cordova stressed several times her commitment to working in collaboration with teachers. During negotiations, educators said they believe Cordova is ready to listen and collaborate more than her predecessor.

“I so deeply admire the passion that motivated teachers to advocate for themselves,” Denver’s school superintendent said. “It’s a passion that I deeply appreciate and my goal now is to, let’s take that passion and let’s work together on the other hard problems that we have.”

Now that some labor peace has been achieved, eyes will turn to overall state funding of schools. Union negotiator Rob Gould pointed out that “we’ve seen across the country how educational funding really hasn’t been where it needs to be.” Prior to signing the agreement, Cordova called for the same commitment, passion and collaboration exhibited by union leaders and teachers in the negotiations to lobby the state for more education money.

The state has withheld nearly three-quarters of a billion dollars from DPS since 2008 due to the “negative factor” and other budget machinations.

“We’re in the shape we’re in because of the lack of will and the lack of collaboration at the state level to invest in our schools,” Cordova said. “There’s no reason why Colorado, one of the wealthiest states in the nation is in the bottom when it comes to financing our schools.”

CPR News' Alex Scoville, Jim Hill and The Associated Press contributed to this report.