Last year, Kari Green, a school nurse in the small mountain town of Nederland, got an email out of the blue. It came from someone who at the time worked with JUUL Labs, the country’s top e-cigarette maker.

The message offered educational services for schools.

The writer, a JUUL consultant and a retired educator himself, described a new company-funded program to help schools prevent students from using e-cigarettes. A detail near the bottom of the email caught Green’s eye. JUUL would soon pilot a device to “not only disable JUUL products in schools but also notify administrators where and when they are being used.”

“I read that and just thought ‘How the hell are they going to be able to do that’?” said Green, who works at the Nederland Middle/Senior High School.

She knew JUULs have a battery and that the device vaporizes nicotine. But the email indicated a level of technological sophistication she hadn’t considered. Just how smart is the technology in a JUUL? Is it able to track users?

From Fitbit to Apple, tracking technology is booming in the health world. Our phones and watches can monitor sleep patterns, calories and steps. The next step could be e-cigarettes, which raises a host of questions about privacy for millions of users, including teens, in the U.S.

A third of Colorado high school seniors now vape and the state topped a national 2018 survey for rates of teen vaping. As e-cigarettes get more high tech, Dr. Tista Ghosh, a mom and the chief medical officer in Colorado, worries about the privacy of those teens.

“If any company, and I’m not picking on JUUL per se, but any company were to monitor and gather data on your use that would be a little bit scary,” Ghosh said. She notes how vaping, often using the JUUL, has caught on, even with middle schoolers. “My son says he sees vaping in the bathrooms all the time, he’s in 6th grade.”

Inside a JUUL there’s a tiny circuit board and a battery. Ghosh wondered what information the devices could potentially collect on minors, now and in the future. “What data are they getting?” she said. “What data are they monitoring? Are they monitoring how much a kid is using?”

What’s Inside A JUUL

The patents for JUUL e-cigarettes offer a hint at their current capabilities. Public health researcher Dr. Greg N. Connolly has spent hours pouring over the documents of a variety of e-cigarette brands. The consultant and retired professor, formerly with Northeastern University and Harvard, found references in the patents to pre-programmed algorithms. Connolly is concerned about what instructions JUUL may have coded into its devices, and whether they could help promote addiction.

“Just what's in those algorithms?” he asked. “Who is really controlling the battery here? Is it the smoker?”

JUUL declined interview requests nor did it address programed instructions in answer to a specific question via email about algorithms in its devices.

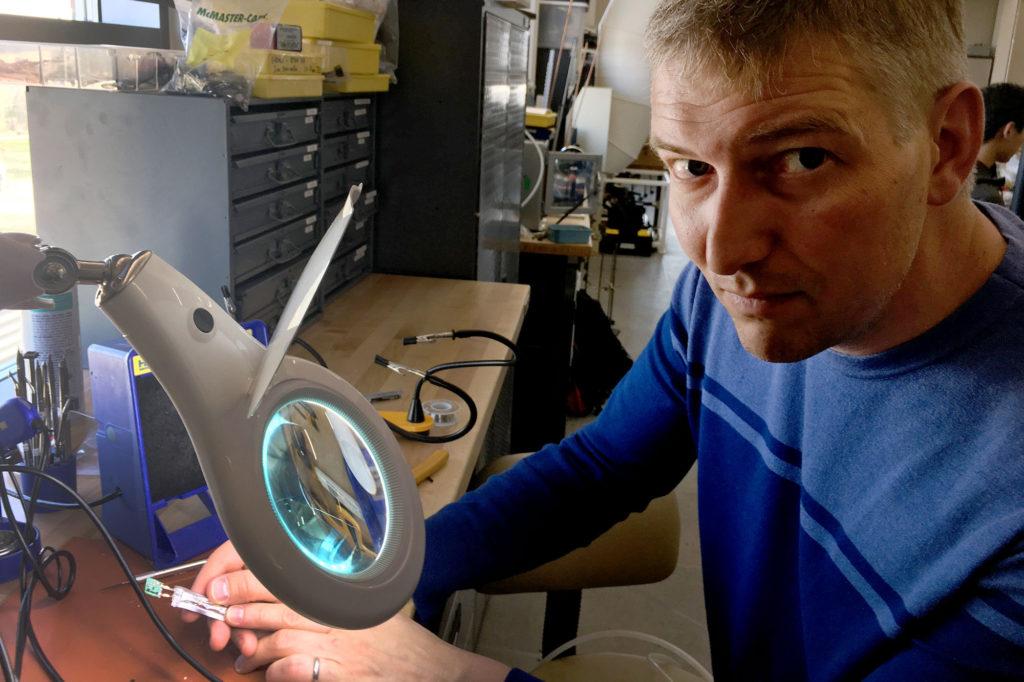

I wanted to know more about what the little computer chip inside a JUUL actually does so I purchased one and visited researcher John Volckens at his lab at Colorado State University. His big focus is usually air pollution, not tobacco. But he is trained as a mechanical engineer.

Volckens grabbed some tools and cracked open the device.

As he took it apart, he described how the e-cigarette works. It has an airflow sensor. When a user sucks on the device, the sensor tells the battery to heat a coil. That coil then turns the liquid in the pod into a vapor.

“You inhale that into your body and it deposits in your lungs and it delivers the product almost directly into your bloodstream,” he said.

That product is nicotine and its delivery is controlled by a fingernail-sized computer chip. The chip also ensures the battery doesn’t overheat or catch fire.

“There are lots of ways where the sensors in this device can be used with a circuit board to make the device act smarter, smarter from the standpoint of delivering the product to the body,” he said.

Volckens suggested I speak with Todd Hochwitz. He’s the lead engineer with a group called Zebulon Solutions, which reverse engineers products to figure out how they work.

“This is definitely not my grandfather’s cigarette, or my father’s cigarette,” said Hochwitz as he examined a JUUL at the company’s office in Longmont.

Hochwitz found no radio, no antennae, no ability to communicate with a computer or over the web. It could happen down the road, “but as of right now it doesn’t look like they are doing that,” he said.

John Daley/CPR News

John Volckens, a professor of Mechanical Engineering at Colorado State University, examines the circuit board from a JUUL.

What’s A JUUL For

The potential for a smarter e-cigarette to learn more about a user would be a major development: Americans are buying millions of JUUL devices each year, along with other vape devices. Volckens said smart technology could play a role in making e-cigarettes hard to quit.

“Of course, one of the primary outcomes of delivering nicotine to the body is to get the body addicted to it,” he said.

The industry says the technology inside e-cigarettes is meant to do just the opposite.

To the idea that e-cigarettes could be wired to deliberately promote addiction, Gregory Conley, the president of the American Vaping Association said, “That is crazy talk. No, it’s temperature control.”

In a video of Adam Bowen and James Monsees, JUUL’s founders, they describe their motivations for developing the JUUL as stemming from a “firm belief that innovation could address all the problems associated with smoking. Fifty years from now, nobody is going to be smoking cigarettes,” Bowen continued on in the video. “They’re going to look back and think ‘Oh my God, I can’t believe people used to do that.’”

The two Stanford grads said they started JUUL to help adult smokers of traditional cigarettes quit. The key to that is to “mimic the experience” of smoking cigarettes, and JUUL’s spokesman Ted Kwong said its technology is designed to ensure the vapor is at the ideal temperature, not promote addiction.

Still, major tobacco companies are developing ways to track e-cigarette users. “The future is in being able to see, visually on your phone, how many times today have I puffed on this device,” Conley said.

JUUL’s CEO, Kevin Burns, told the Financial Times recently it is testing an app that would monitor via Bluetooth how many puffs a vaper has taken and “coach” them to manage their nicotine product. The point is to help users quit traditional cigarettes, he said. He described how future devices would require users to verify their age, in order to limit underage use.

"We take data privacy very seriously. Data insights enable JUUL Labs to continually improve our products, and to better help adult smokers in their switching journey,” said JUUL’s Kwong. “All collected data is securely and privately stored. JUUL Labs will never sell customer data or share it with third parties without a person’s explicit permission and in compliance with applicable legal and regulatory requirements.”

And the Vaping Association’s Conley said that advanced technology would get plenty of review before reaching consumers. “All of these developments, all of these innovations will need to go through the Food and Drug Administration, so you’re going to see a lot of safe features,” he said.

That’s not enough to reassure Robin Deterding, a doctor and pediatric lung specialist at Children’s Hospital Colorado. Deterding said the FDA “needs to own this” and isn’t doing enough to keep young people safe.

“We are behind in this epidemic and I look to the FDA as the federal regulating agency to take a strong lead on this and not pass on it.”

In a comment, the FDA said, "[The FDA] has and will continue to tackle the troubling epidemic of e-cigarette use among kids."

It said it has updated its guidance for submitting applications for new tobacco technology, which includes reviewing "the likelihood that existing users will stop using such products and the likelihood that those who do not use tobacco products will start using such products."

The technology appears to have raced ahead of regulation. Public health researcher Greg N. Connolly grew more worried after the FDA’s recent greenlight of sales for the iQOS, a new electronic cigarette device with Bluetooth technology. Its maker is tobacco giant Philip Morris International, a rival to JUUL. As new products like the iQOS arrive, Connolly said the FDA hasn’t looked closely enough at what’s already inside e-cigarettes.

“FDA should be regulating circuit boards, yet we haven't heard one peep out of FDA of the presence of a circuit board,” he said.

Longtime tobacco researcher Stanton Glantz shares that concern, especially as money pours into the fast-growing industry. Top U.S. cigarette manufacturer Altria invested nearly $13 billion in JUUL, giving it a 35 percent stake in the company.

“To me, it’s Facebook meets a drug cartel,” said Glantz, who directs the Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education at the University of California San Francisco. “These companies are selling addictive drugs and they should not be allowed to do person by person monitoring of behavior.”

Glantz, along with colleagues from Stanford University and Georgia State University, filed a letter with the FDA in May that called on the agency to “use its existing authority” to prohibit e-cigarette design features that “maximize addiction potential and appeal to youth.”

Connolly, the researcher, said the FDA put off regulating e-cigarettes until 2022. “In doing so, they’ve allowed a plethora of next-generation e-cigarettes to come onto the market.”

In the meantime, the larger fight over the safety of e-cigarettes is now playing out in the courts. In May, the parents of a 15-year-old teen they say is addicted to JUUL’s e-cigarettes filed a class-action lawsuit in Florida against the company. A similar suit was filed in San Francisco earlier in 2019.

Glantz said studying and regulating the future of e-cigarette technology couldn’t be more urgent. According to a report from the U.S. Surgeon General, vaping by teens is now an epidemic. Without checks, Glantz said, we could see a whole new generation addicted to nicotine.

Editor's Note: Updated 5:26 p.m. Monday, June 17 with comment from the FDA.