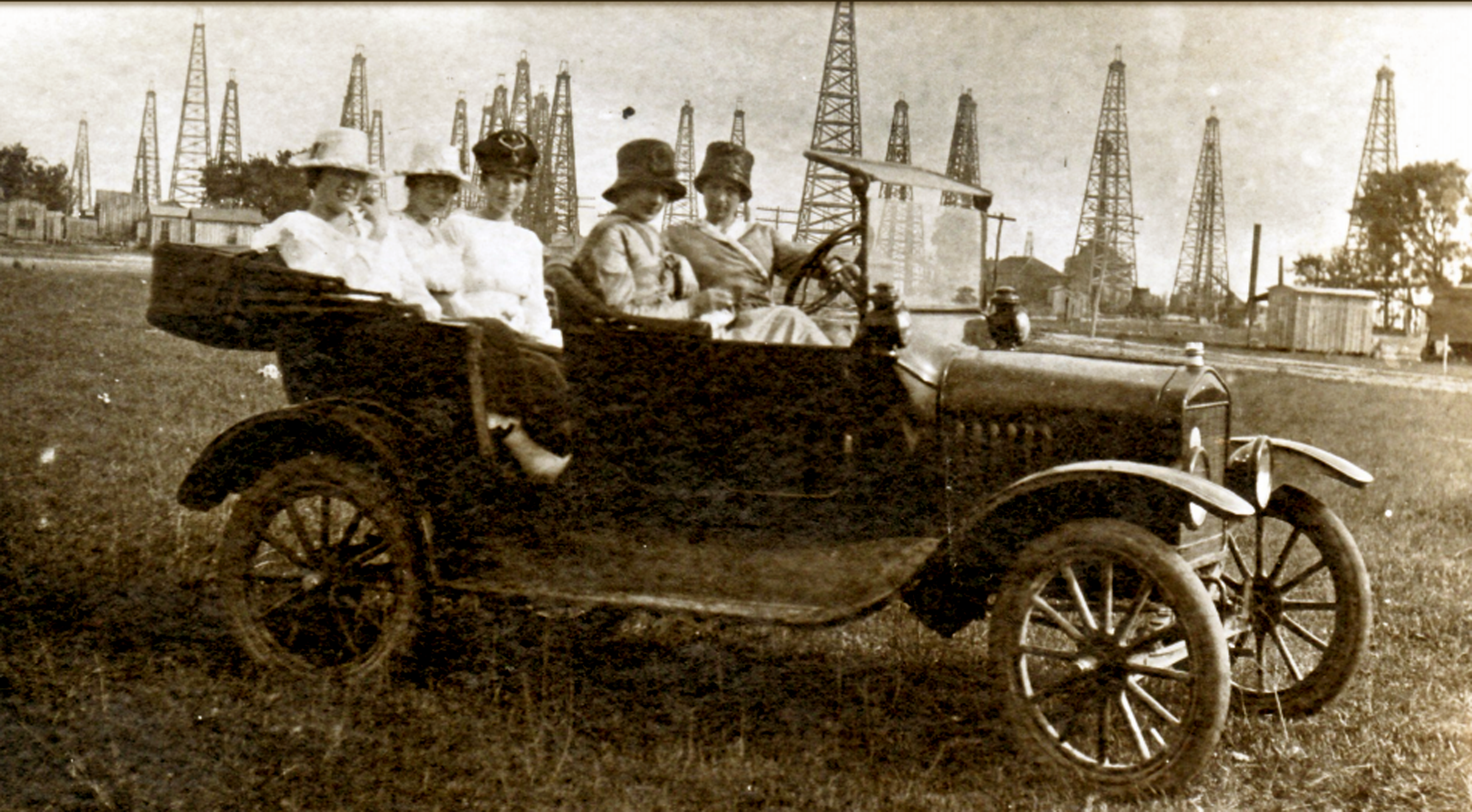

Oil barons, roughnecks -- these words given us by the petroleum business have long made it seem like it's solely the realm of men. “Anomalies: Pioneering Women In Petroleum Geology 1917-2017,” a new book by Denverite Robbie Gries, paints a different picture.

She tells Colorado Matters host Ryan Warner about the stories of female petroleum geologists going back a hundred years who battled sexism and raised families while making significant scientific discoveries.

Read An Excerpt:

Prologue An Exciting Day for the First Female Petroleum Geologist Imagine what it was like when news of a potential strike came to the ears of a gutsy geologist, anxious to be part of the petroleum world: Reba Masterson loaded up her 1929 Model A Ford for her trip from San Antonio to Henderson, Texas over 300 miles away in East Texas. She had heard reliable rumors that promising shows had been detected in “Dad” Joiner’s third attempt drilling the Daisy Bradford lease. The previous two wells that showed promise ended as failures with stuck pipe or other complications. This one, the Daisy Bradford #3, had been drilling for a year and a half and was plagued with poor equipment and Joiner running out of money. Worse for Joiner, his lease was expiring. He had already managed to get two extensions. The drilling was finally improved with a new drill string, but a drill stem test of an oily zone had failed. In desperation, they had run casing and bailed unsuccessfully for days. Now, they were making one last ditch effort and were swabbing the zone. Thousands of people were camped nearby throughout the testing. Somehow, optimism prevailed despite the discouraging results. Joiner was housed in nearby Overton, Texas, but had apparently rushed back from a Dallas trip for this round of testing. Reba knew there would be no place for her to stay in Overton. She was lucky to book at the Davenport Hotel in Henderson. It was 5 a.m. and she was not sure if she would get there before dark, especially if there was traffic with other “rubberneckers.” Though her new car could make 60 mph, with so many small towns and high traffic, she would be lucky to average 40 mph. Reba had been chasing discoveries for over 20 years off and on, finding that she could often parlay her geology expertise into an interest in leases surrounding discoveries as land owners and investors were hungry for “scientific” opinions. She had already done some scouting around this area, identifying leaseholders that might have interests she could acquire. She was a tiny woman, maybe 5’ 2” and very slim. But at age 48, she was a tough and determined business woman and a very competent geologist—the first professional female petroleum geologist in the country. Though she never thought about that, she just did what she liked to do. She had never worked for a company; she just got her degree and started applying geology to finding oil. Getting that degree, however, was a story in itself! Usually, she traveled with her good friend and constant companion, Eunice Aden, but on this fine October day in 1930, she would be traveling alone. Eunice was at Medina Lake, taking care of new building at their Kiva Camp for girls. Reba didn’t like traveling without Eunice…even with her trusty .32 caliber pistol her father had given her when they were involved in an East Texas lawsuit where she had been threatened if she testified. She rarely went anywhere without her pistol. But, Eunice provided more protection because she had a .38, and, she was taller, larger, and very athletic. Formidable, she was also gregarious and always surrounded by friends. Yes, Reba felt safer when Eunice was with her. As Reba drove eastward into the rising sun, she let her mind drift back to her Galveston days. Her father frequently entertained visiting oil men. In 1901, he and a few colleagues organized The New York and Texas Oil Company, and it was there that she met Dad Joiner on one of his many Galveston visits. It was not only a nice place for a small vacation, it was a great place to mingle with other oil men and investors. Her only irritating memory was when she let him beat her in a poker game so many years ago—losing an oil lease to him! She hoped that one never came in big, making her feel the fool! Branch Masterson, her father, had instilled a fascination for the oil business in her, and they often had occasion to learn of abandoned properties that could be bought for back taxes. He made his living in law, but he enjoyed dabbling as a “vacancy hunter” that way, picking up properties and their attached mineral rights for back taxes. Despite his interest in the oil business, she had an awful time fighting with him to let her go to college and study geology. But, he got tired of her nagging every night at the dinner table and, maybe more importantly, realized when she turned 26 she was probably never going to get married and, perhaps, would need a career! She hadn’t wanted to study law like her brothers. She liked being in the thick of an oil field. In 1908 when she started at the University of Texas in Austin, she was only the second woman in the geology program. This was a path to give her the excitement of travel, business, and science all rolled into one. She had been 19 when the 1900 Galveston Hurricane took her mother’s life, and the lives of so many other family members, that forced great maturity and responsibility upon her. At the time, Reba remembered being pushed to her limits with the responsibilities of rebuilding the family home, taking over the domestic duties her mother once managed, caring for her 16-year-old brother, Thomas, and, of course, caring for her father. Her older brothers and older sister were long gone from the house. But her sanity was kept in place by the enthusiasm she had earlier shared with her father about the oil business. After the Hurricane, when Spindletop came in a few months later, they welcomed the distraction and speculated about what opportunities might be available. . Saratoga field was discovered the next year, Sour Lake in 1902, and Goose Creek in Harris County in 1903. She and her father followed it carefully and took to driving to these places and learning to scout any new drilling. He would check out the possibility of buying properties and minerals as they went along. She learned how to do the same. They were lucky enough or smart enough to acquire leases in the Damon’s Mound area after J. M. Guffey’s early drilling tests failed in 1901 or 1902. No accident, she was at Damon’s Mound when it blew in November 15th of 1915. Had it not been for the August 1915 hurricane bringing her back from Colorado, she would have missed it there…her first time to witness a blow out! Their leases, long considered speculative, proved fruitful indeed for the Masterson family! As she continued her drive toward Henderson, she thought how much she still missed her father—though he had been dead for ten years. She had a wonderful, but convoluted, relationship with him. Reluctant though he was to let her go to college, he came to appreciate her when she gained so much knowledge in Austin and Boulder. He was proud of her geologic expertise and her business sense. She remembered when, as a diversion from her studies at the University of Texas, she and her father had visited Colorado and she fell in love with it. She wasn’t through with her geology degree, but she knew she could finish while considering oil properties in the Rockies. They had considered acquiring leases around the Boulder oil field—so exciting near the little foothills college town—but the field was in serious decline by the time she moved there in 1911 to start coursework at the University of Colorado. Her five years of studying and looking at the structural geology of Oklahoma, Louisiana, and Texas were equally trying, but she could, more easily, get back to her home in San Antonio for breaks. She had plenty of resources for her studies by visiting the Bureau of Economic Geology in Austin. She enjoyed a friendly relationship with the geologists there but was glad she did not have to depend on making a living there…living from state budget to budget was not her cup of tea. As Reba stopped to service her car in College Station, she thought about the college rivalry between UT and Texas A&M. Silly, but fun. She was more attuned that morning to the good fortune of having paved roads. And more service stations. She loved that she did not have to crank the car as she did in her early years of chasing oil discoveries. Nor, did she have to deal with as many flat tires and breakdowns as when she was running around in oil fields after she left the University of Colorado. She had planned to start right away in the oil business when she finished CU but, once again, a hurricane altered her plans. She had to finish her last few credit hours at CU by correspondence and didn’t get her geology degree awarded until 1916. As soon as possible, she started her independent study of oil fields, of new exploration efforts. Traveling was so much more challenging then. Her excursion through Kansas, Illinois, West Virginia, Pennsylvanian, and Kentucky doing reconnaissance work was grueling but wonderful. Driving that old Model T was hard and physical, but the muddy, god-awful roads were really a pain. It was easier in the summer months when Eunice could accompany her. Many times, she would never have made their destination without Eunice’s help or without the help of strangers, or both! Gassed up, she continued her drive toward Henderson. She knew these roads well and the small towns she had to drive through—out of San Antonio and into Seguin where her friend, Hedwig Kniker, came from, a fellow UT student and now successful geology consultant. She drove on through Lockhart, Bastrop, Bryan; ahead of her was Crockett, Weeping Mary, Alto, and Rusk. Traffic was beginning to build, certainly most cars heading to the same place she was going. Late in the afternoon she pulled into Henderson and found the Davenport Hotel. After checking in, she changed into boots and clothes that would work out on a drilling location. She was glad that women had begun to wear high boots and jodhpurs in the field unlike the old days of formal dresses that she had worn to Damon’s Mound when it blew. Henderson was packed with cars and people, many heading out to check the activity at the Daisy Bradford. The usual oil field trash was in abundance—she was used to dealing with that. She recognized an oil scout she had come to know and he caught her up with news about the testing at the well. He told her the crew had been bailing for almost two days and had started swabbing the well. He thought the well could prove itself very soon, one way or the other. She hurried to her car and headed west out of town. It was easy to find the way—cars packed the roads. When she got as close as possible, nearby landowners were charging people to park and she took advantage of it. “My god!” She thought. “There must be several thousand people here.” As she left her car, she heard the crowd begin to grow silent. She whispered to someone, “What’s happened?” He whispered back, “They heard something in the drill pipe. We’re listening.” She couldn’t see but suddenly heard people yell and shout as a spurt of oil came up the casing and onto the surface! She, and all eight or nine thousand spectators were rewarded as oil began to pulse out of the well bore, then up and over the crown—a gusher! At last! She was happy for Dad Joiner. She watched in awe and pleasure as history was once again being made in Texas. Could there be anything more exciting? She knew she had work to do, too. Could she get a piece of the Ashby lease nearby? She thought about the contacts she had made and started working on her strategy to find a piece of the action. How far to go? Rusk County only? Or move out to Green County? Smith? She had a lot of work ahead of her. Excerpt from "Anomalies: Pioneering Women In Petroleum Geology 1917-2017" by Robbie Rice Gries. Copyright © 2017 by Robbie Rice Gries. Used by permission. All rights reserved. |