Meli Holohan was at the lockdown drill that triggered her son’s insomnia.

She had come to Cottonwood Creek Elementary School to read in his fourth-grade class when she was given the head-ups during check-in.

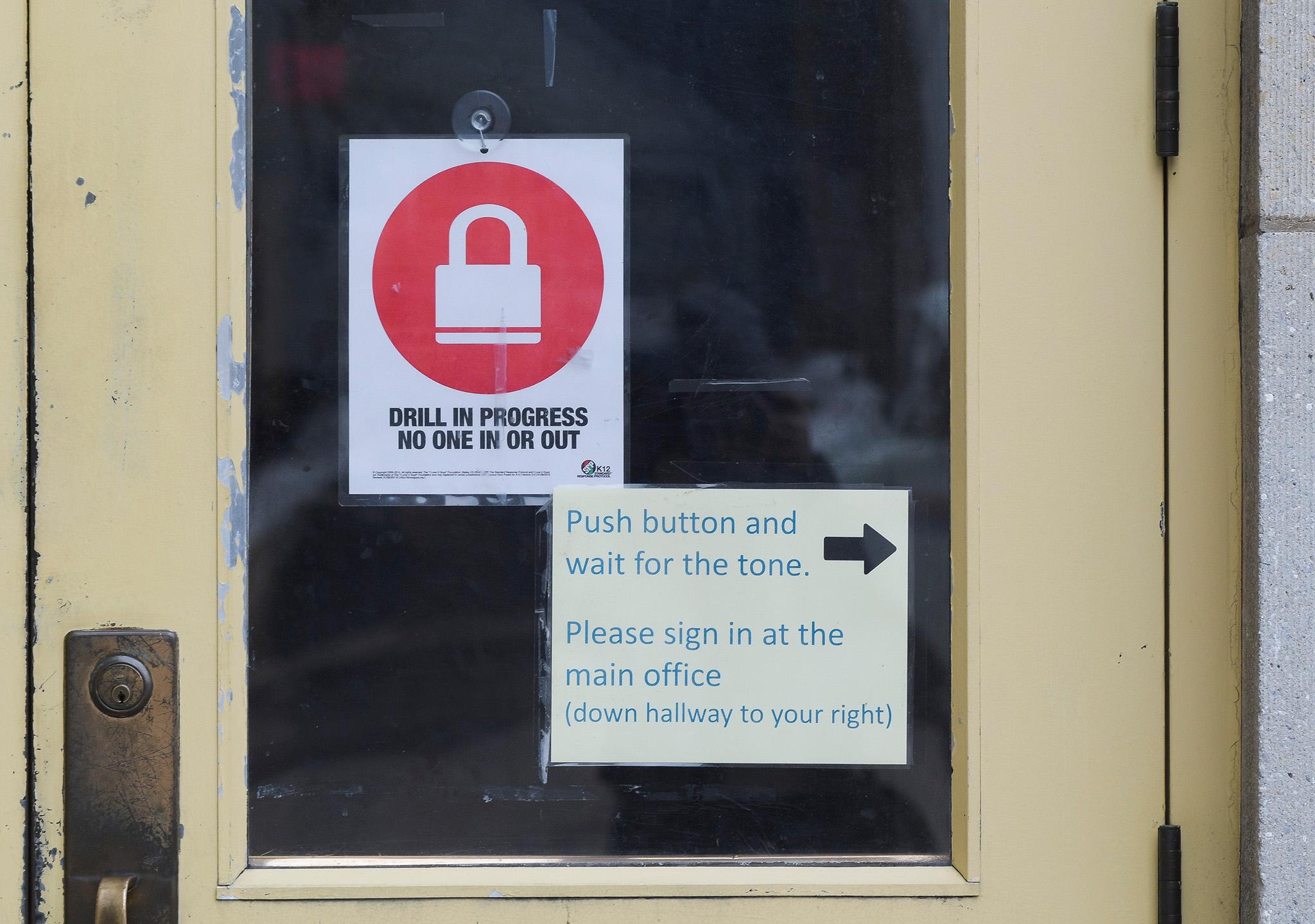

The principal’s crackly PA announcement triggered a well-practiced routine: One child taped a sheet of paper over the slim window on the locked door. The lights were dimmed, and Holohan’s son huddled quietly with his classmates in the corner.

Holohan’s mind flooded with questions as she watched. She found herself looking at her son’s teacher and wondering what she actually wanted him to do in case of a real active shooter.

“What can I actually expect this man to do?” Holohan said. “He has a life that is valuable for him. It makes you ask all these questions that have no answers.”

- Since Columbine: How Effective Are Lockdown Drills?

The effects of that drill lasted long past that day, for Holohan and her son. He has trouble sleeping, and isn’t feeler any safer. Holohan has the advantage of being a psychologist, and focuses on affirming him, telling him that it is hard and scary, but also that the reason behind all of these drills is to keep him safe.

“I can’t tell him ‘That’s going to be fine, buddy.’"

“That’s not what he needs to hear, and he’ll know it’ll be bullshit,” Holohan said.

That matches the advice of Dr. Franci Crepeau-Hobson, a school psychology professor at CU Denver.

She says kids and adults can come out traumatized from even the most sensitive drills, nevermind the active shooter drills that go too far by hiring actors to pretend to shoot students and firing fake tear gas canisters.

“Doing a regular old lockdown drill is sufficient. You don’t have to take that next step,” Crepeau-Hobson said.

But done right, drills can be a powerful tool to help kids stay and feel safe. How parents communicate with their kids afterward is crucial in making the experience effective, not hurtful.

“If we frame it as, ‘We’re going to take every step possible to keep you all safe, and so we’re going to practice keeping you safe, and helping you know what to do to keep yourself safe,’” Crepeau-Hobson said. “That can actually be empowering.”

“The ‘why’ is really important here."

Like Holohan did with her 4th grader, Crepeau-Hobson said it’s important to not make false promises and be honest, even if the chances of being involved in a school shooting are miniscule. Tell your kid, “Drills are scary, but they will help keep you safe in case something bad ever happens,” instead of, “This will never happen to you anyway, so don’t worry.”

She recommends checking out the National Association of School Psychologists’ resources for parents about talking to kids of all ages about violence in schools. Advice includes:

- Reassure kids that they are safe, but make sure to validate their fears and feelings.

- Make the time to talk. For your younger kids, communicating their thoughts may take the form of drawing or playing, not as a conversation.

- Tailor your explanations to be age appropriate. As your children enter middle and high school, welcome their thoughts and opinions on gun control and school safety.

- Review safety procedures with your kids, and help them identify an adult at school that they trust.

- Keep an eye on your child’s sleep patterns, appetite and anxiety after drills. Don’t be afraid to talk to a mental health professional for help, especially if your child has experienced past trauma or has special needs.

- Limit how much your younger kids see news about school shootings or other violent events on television.

- Maintain a normal routine, and encourage them to continue hobbies and activities.

She said schools and families should give as much advance notice as possible, and focusing on the “why” — they’ll keep you safe if the time comes — behind the exercises.

Holohan said her son’s fears have faded as the weeks since the drill go by. Their talks about how his teachers have a plan and a reason for the drills has stuck with him, she added, and he seems to believe again that the grown-ups have it under control.

“That mirage has been reestablished to some degree,” she said.

Crepeau-Hobson does note that exceptions must be made with students on the autism spectrum or a history of trauma, where a drill can be more stressful and disruptive.

It’s an issue Holohan knows well: Her younger son, in second grade, has autism. His school has a separate strategy for special needs classrooms during drills, but Holohan is still anxious about the possibilities.

“We have concerns about what’s going to happen in a crisis to that kid,” Holohan said.

It’s important for parents to advocate for their kids who have special needs, especially if a school doesn’t have alternative plans in plan like Holohan’s son’s.

“If a parent does have a kid with a disability, make sure they’re talking to school personnel,” she said