Denver writer Gary Reilly churned out novel after novel during his lifetime but he died before any of them were published.

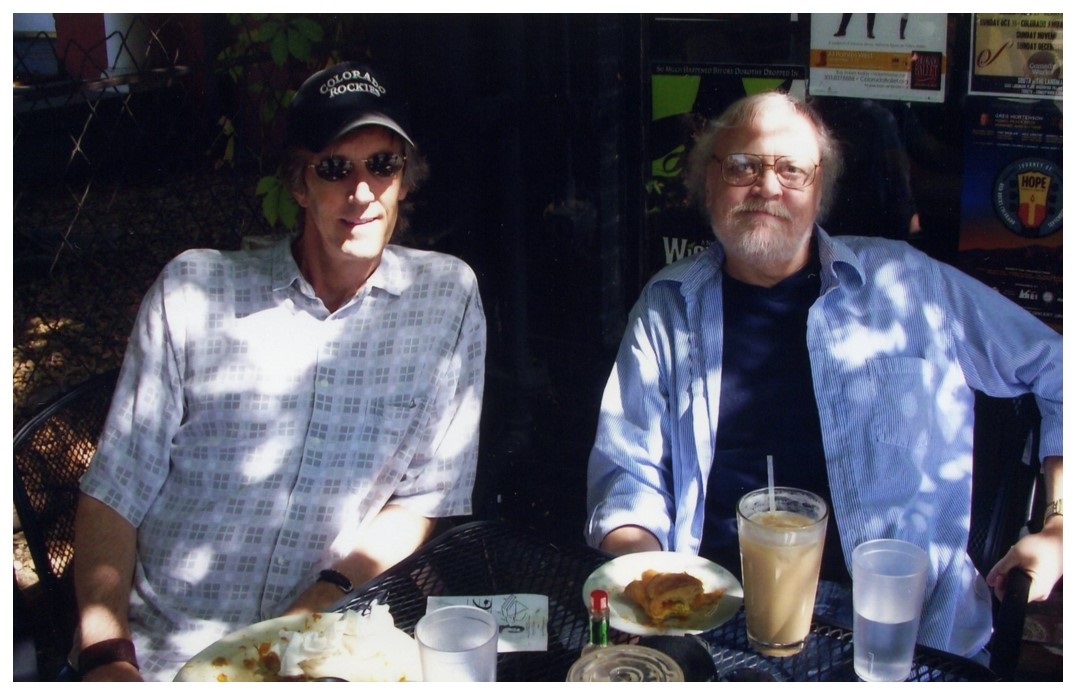

Now, two of his friends are making up for lost time. Tomorrow, Mark Stevens and Mike Keeefe, both former employees at The Denver Post, will release "Devil's Night," the 10th novel they've published since Reilly's death from colon cancer in 2011.

Mark Stevens, who's now a mystery writer, spoke with CPR's Andrea Dukakis.

Read An Excerpt from Gary Reilly's first published novel, "Pick Up At Union Station":

Chapter 1 I was sitting inside my taxi outside the Oxford Hotel when a call came over the radio for a pickup at Union Station. I had just dropped off a fare at the hotel, which is half a block away from the train depot. It was six-thirty Wednesday evening, it was April, and it was raining buckets. Don’t ask me how the word “it” can be so all-inclusive, but it is. I guess that’s the magic of language, but I didn’t have time to parse the baffling splendor of the King’s English because I had thirty minutes to drive my cab back to the Rocky Mountain Taxicab Company (RMTC) before my shift ended. I also had two seconds to deliberate taking the call. If I waited three seconds, another cabbie might jump the bell. The weather was so inclement that cabbies all over Denver were reaping the whirlwind. By this I mean that people were calling for taxis, so it was a seller’s market and I was one of the rip-off artists on duty that night. I caved in fast. Union Station was thirty seconds away and I have an uncontrollable craving for money. Money is like all of my uncontrollable cravings—it makes me do things I sometimes regret, although the regret usually takes place after the craving has been slaked and I’m sitting around idly thinking about nothing. Ironically I sometimes find myself regretting not having slaked a craving. If you go on dates, you probably know what I mean. “One-twenty-three!” I said, grabbing the microphone off the dashboard. “Union Station, party named Zelner,” the dispatcher said. “Check.” I hung up the mike and made an illegal U-turn on 16th Street. To my knowledge “illegal” is the only kind of U-turns they have in downtown Denver. I drove across Wynkoop Street and into the driveway that fronts Union Station. Coincidentally the driveway is shaped like a U. I figured the customer for someone who had just gotten off the Zephyr coming from either Chicago or Oakland. I once rode the Zephyr to Oakland. So did Jack Kerouac but not at the same time. I pulled up at the cabstand and peered through the pouring rain toward the front door of the station, hoping the fare would be standing by the entrance waiting anxiously for his ride. Not that I like it when people are anxious, but it hurries things along. I had my fingers crossed that the fare would ask me to take him to one of the big hotels in midtown—the Fairmont or the Hilton. I might pick up a fast five bucks and still have time to make it back to the cab company before my shift ran out. The trip would come to only two bucks or so, but people tip like madmen when it rains, especially when their taxis show up fast. I had shown up fast. Maybe too fast. I sat staring through the wet windshield toward the front door of the terminal. The wipers were going back and forth but the rain was coming down so hard that they were virtually useless, like everything else in my life not counting TV. I didn’t see anybody. This made me anxious. It meant I might have to get out of my cab and go into Union Station and look around for my customer. On the upside I would get to yell “Rocky Cab!” at the top of my lungs, which I have done before in the terminal. I enjoy that. My voice echoes off the high ceiling and makes me feel like a railroad conductor. I wanted to become a conductor the first time I hollered “Rocky Cab!” in the terminal but by the time I got back into my cab the ambition had faded, like most of my ambitions. If you’ve ever seen Grand Central Station in New York Pickup at Union Station 7 City, Union Station is sort of like that, in the way that Denver is sort of like a city. But I had one problem that night. If I walked into Union Station I would get wet. As I said, it was “raining buckets.” Normally I don’t employ clichés but I have learned over the years that people respond more readily to clichés than to James Joyce, who once took an entire page to make it clear to his readers that it was snowing all the hell over everything in Ireland. Okay Jimbo, we get the point, but where’s the plot? Aaah, don’t get me started on James Joyce. My anxiety increased. I could feel my left hand reaching for the door handle. But I kept staring at the brightly lit doorway of the terminal trying to “will” my customer to appear with a suitcase. Cab drivers do this frequently. The only thing besides the rain that stopped me from getting out and rushing toward the terminal was the fact that I had gotten there so quickly that I knew the customer might still be standing at the phone booth gathering his things together and sighing with resignation, believing that his cab might never show up. Customers do that frequently, especially when the weather is bad, or when cabs are tied up because there’s an NBA championship game being played by the Denver Nuggets. That never happens frequently, believe me. I glanced at my wristwatch and noted that barely a minute and a half had passed since I had taken the call. This was what ultimately kept me inside my taxi. Nobody in their right mind would expect a cab to show up that fast. The fare might even be at the snack counter buying cigarettes or a cup of coffee before going to the door and peering out to see if his cab had arrived. That was what I was thinking. I was fabricating scenarios. I was making excuses for my fare who had yet to appear in the doorway, which was really starting to annoy me. I dislike being annoyed at fares because they give me money, and I like people who give me money. It’s the instant gratification in me. It makes me impatient with people who don’t give my inner brat what it wants right now! Then a thought occurred to me that made my heart sink. What if another cabbie—say a Yellow Cab driver—just happened to be at Union Station when my call came over the radio and he had stolen my fare? I know how that works. I’ve done it plenty of times at the mall. I hate it when other people treat me the same way I treat them—it makes me feel like such a commoner. I began to audibly curse the Yellow Cab company when suddenly my back door opened and a man climbed in wearing a snap-brim hat and a trench coat. He scared the hell out of me. I reached to the breast pocket of my T-shirt where I keep a nasalspray bottle filled with ammonia, but let’s not delve too deeply into that. “Did you call a cab?” I said. “Yes,” he said in a voice so husky that I thought he had a cold. “Is your name …?” I started to say, but I abruptly stopped. “What’s your name?” I said, feeling clever. “Zelner.” “Where to, Mr. Zelner?” I said, dropping my flag and turning on the meter. He reached inside his trench coat and began digging around for something. Not a gat I hoped. Maybe a nasal-spray bottle. I reminded myself not to loan him my own bottle. I had learned that the hard way. He pulled out a small square of paper and held his arm across the front seat. “I need to go here,” he said. I glanced at his face as he spoke. He had a ruddy face. He looked older than me, for what that’s worth. I’m forty-five. His hat was dripping water. It occurred to me that he might have been standing in the rain all this time waiting for me. This made me wonder why he hadn’t come dashing to my taxi as soon as I pulled up at the stand. I switched on the overhead light to read the paper. This threw his face Pickup at Union Station 9 into shadow. The address was right across the Valley Highway in North Denver, at a place called Diamond Hill, a small business park. “Is this very far?” he said. “No, sir,” I said, putting the cab into gear. “Maybe five minutes away.” He sighed with what I took to be satisfaction, pocketed the paper, and sat back. I turned on my headlights and pulled out of Union Station. Already I was thinking what a sweet deal this was. I would probably earn five dollars from this ride, and after I dropped him off I could swing down to the Valley Highway and head north to Interstate 70 and over to the cab company—or the “motor” as we drivers call it—and sign out with at least ten minutes to spare. This was the kind of ideal situation that cabbies are always hoping for. It rarely happens, but when it does happen you have to milk it for all the joy you can get. When you drive a taxi for a living, you rarely get the opportunity to feel ecstatic. “Is it permissible to smoke inside your taxicab?” Mr. Zelner said, as we pulled away. I glanced in the rearview mirror and nodded a preamble to saying yes. I was using the power of positive body language to indicate to him that I was amenable to anything that would increase the size of my tip. “Yes sir,” I said. “There’s an ashtray in the armrest on the door.” “Thank you,” he said. He spoke very slowly and distinctly with a foreign accent. By foreign I mean European, although I do realize that Europe itself is not a country in spite of attempts by tyrants throughout history to alter that construct. I heard the rustling of fabric, the faint scrape of fingers dealing with cellophane, then the man leaned forward and said, “I am sorry but I do not seem to have any matches. Is it possible that you have matches or a lighter that I might make use of?” “Yes, sir,” I said. I reached for my toolbox and popped the lid open. I keep all sorts of things in my box, like matches, small change, toothpicks, 10 Gary Reilly pocket Kleenex, anything that might feasibly increase the size of my tips. I had to refrain from saying, “Want me to smoke it for you, pal?” That’s an army joke guaranteed not to increase the size of your tips. I’ve often wondered whether “army joke” is an oxymoron, but let’s move on. I handed him a book of matches and told him to keep it. I pick up free matches at 7-11 stores, even though I don’t smoke cigarettes, although I used to. I pass the matchbooks along to people who are trying to give up smoking. Name anybody who smokes—I guarantee you that he’s trying to give it up. The only reason I succeeded at giving up the habit is because I have always been good at giving up. “Interesting odor,” I said, complimenting his smoke. “What brand is that?” “Gauloise,” he replied hoarsely. I nodded as if I knew what a golwoss was, then headed down to Speer Boulevard and took the 14th Street viaduct across the valley. We were halfway across when I saw a flash of red lights in my rain-spattered rear window. They had come on suddenly, as opposed to appearing in the far distance the way emergency vehicles often do, such as fire trucks and ambulances. I groaned inwardly, then glanced at my speedometer. I was doing the speed limit. Obeying the law is a habit I got into the same day I received my taxi license fourteen years ago. It’s one of my better habits. Given the fact that most habits are performed unconsciously, I figured that obeying the law would be a good habit to nurture assiduously. But I still groan when red lights flash on. Habit. “What is that?” Mr. Zelner said, turning around and peering out the rear window. “I believe it’s a police car, sir,” I said, as I took my foot off the accelerator. “Why is a police car following us?” he said in a voice that communicated suppressed panic. I am familiar with that voice. I practically invented it. If you ever want to hear it, just call my answering machine. Pickup at Union Station 11 “I don’t know,” I said. “I must have violated a traffic law.” I had no intention of pulling over and stopping in the middle of a viaduct under wet-weather conditions, so I gave my brakes a couple of taps and turned on my right blinker to signal to the policeman that I was aware of his presence. I intended to pull into a gas station at the west end of the viaduct. “Can you elude him?” Mr. Zelner said. “What?” I said. “I am late for an appointment.” I glanced at the rearview mirror. Mr. Zelner was turned almost completely around, peering at the red lights of the cop car that was perhaps thirty feet behind my taxi. “I have to stop, sir,” I said. “I can’t try to elude a policeman. I would lose my license.” He turned around and looked at me. Then he began touching the pockets of his coat. For one second I thought he was going for a gat. By now we were at the far end of the viaduct and I had to take care of the business of pulling into the station and parking beneath a roof that protected the gas pumps and possibly diving out of my taxi. I could hear Mr. Zelner making rustling noises in the backseat. As I wheeled into the parking lot I glanced at the mirror and saw him tamping out his cigarette. He closed the ashtray and twisted around to look at the cop car, which had parked directly behind me. “This is a local policeman, yes?” Mr. Zelner said, turning and facing front. I craned my head around and looked into the backseat. His arms were folded and one hand was touching his chin. I forget which hand. The only thing I remember is what his body language communicated: he was prepared to bolt. I had seen this before in other passengers, which we cabbies refer to as “runners.” These are people who hop out of a backseat at intersections and run away without paying. I don’t know who the genius was who invented the word “runner,” beyond the fact that he must have been a taxi driver. I suppose that many a hired coachman in Auld Angland must have chased “runners” down the foggy streets of London town. “Yes,” I said. “It’s a Denver Police Department car.” He nodded, closed his eyes, and bowed his head as if to hide his face. His body language was freaking me out, especially the syntax of his skull. I faced forward, rolled down my window, and prepared myself mentally for the excruciating experience of signing a traffic ticket. You know what I’m talking about. Don’t even try to kid me. “Good evening, officer,” I said. “Good evening, sir,” he said. “The reason I pulled you over is to let you know that your left-rear taillight is out.” I started to say, “It is?” but I had been trying for years to wean myself from the habit of making cops repeat themselves. “I wasn’t aware of that,” I said. He nodded. “I’m not going to give you a ticket. I just wanted to let you know about it.” He ducked his head and glanced into the backseat. “Running a fare?” “Yes, officer.” “All right. You might be able to buy a replacement bulb in this station. If not, you better get that taken care of as soon as possible.” “I’ll do that. Thank you, officer.” He tapped the bill of his cap and said goodnight, then walked back to his car. As he pulled away and drove up Speer Boulevard, I started thinking about the break he had given me. If I had been a civilian he probably would have ticketed me, but cops always seem willing to give cab drivers a break. Cops and cabbies have a lot in common. We drive automobiles on the job, we work the mean streets, and we frequently deal with weird strangers. The list is almost endless but it’s not. At the bottom of the Pickup at Union Station 13 list is the fact that cab drivers don’t carry .38 caliber revolvers. At least I don’t. Bottled ammonia is as far as the Founding Fathers were willing to let me go. “I’ll take you up to Diamond Hill first, sir,” I said glancing at the mirror. “Then I’ll come back here and replace the light bulb.” He didn’t say anything. I put the transmission into gear, pulled out onto the street, and made my way up to the business park in silence. I thought about turning on my Rocky Cab radio and listening to the dispatcher, but I decided against it. My fare would be getting out in a couple of minutes, and after I replaced the bulb I would be heading back to the cab company to sign out for the night, so I wasn’t interested in listening to the perpetual drone of addresses on the receiver. I would opt for AM radio as soon as I was alone, which is what I usually am when I rock to the Stones. Another option would have been to fill the silence by starting a conversation with Mr. Zelner so that we could drift idly down The Pointless River to The Sea of Forgotten Chatter. But I hate talking to people as it is, and I saw no reason to jump-start a conversation with a man who would be getting out of my backseat in less than two minutes. When you’ve driven a taxi as long as I have, you get good at estimating how long it will take before a fare climbs out of a backseat. I’m usually right to within a range of ten to fifteen seconds. I’m not bragging, just stating a scientific fact. But I was wrong. Mister Zelner would not be climbing out of my backseat within two minutes. He would never be climbing out of my backseat. I guided my cab into an asphalt parking lot and stopped in front of a building. I looked at the meter, switched on the overhead light, and turned around in the seat. “Three-twenty,” I said, meaning three dollars and twenty cents. Mr. Zelner appeared to have fallen asleep. I won’t insult your intelligence by pretending that I did not know he was dead. I knew it as soon as I looked at him. I will admit it was odd that I knew he was dead, because the only other dead body I knew of that I had encountered “on the job” was in a mortuary. I was delivering flowers for a living at the time. But since it was a mortuary I had no problem figuring out that the horizontal body on the clinical table was a corpse. However on that rainy night in April I felt psychic as I looked at the fare in my backseat. I felt every hair on my body stand erect. I don’t want to get grotesque here but I mean every hair, and I sport a ponytail. There was something about the way he was sitting that told me he was a goner. He wasn’t just slouched against the backseat with his chin resting on his chest with a bit of drool hanging from his lower lip, while his partly curled palms lay slack on his lap. He looked “crumpled.” I guess that’s where the phrase “crumpled corpse” comes from. I got out of the driver’s seat fast. I leaned down and looked through the window and said loudly, “Mister Zelner, we’re here!” But I did not say it loud enough to wake the dead. reprinted from Pick Up At Union Station by Gary Reilly with permission of Running Meter Press. Copyright (c) Gary Reilly, 2015. |