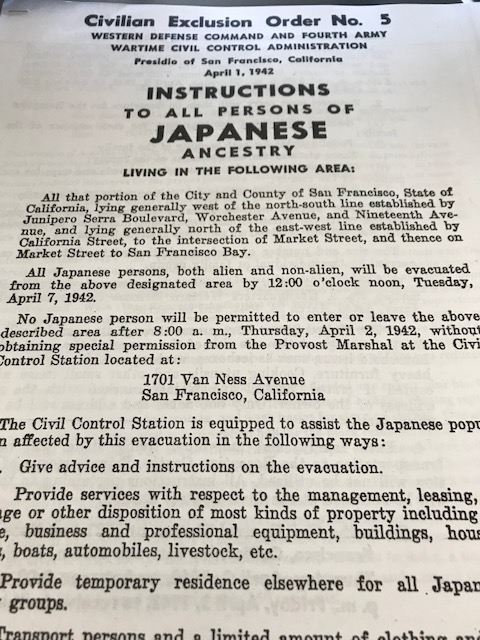

Bob Fuchigami was just 11 years old when his family received the notice in April 1942.

"All Japanese persons, both alien and non-alien, will be evacuated from the above designated area."

The Fuchigami family, two parents and eight children, were forced to leave their central California ranch. They didn't know at the time, but they were heading to southeastern Colorado, and the Amache Japanese-American internment camp.

Every year, Japanese-Americans make pilgrimages back to what is one of the darkest chapters in not just their lives, but in Colorado and America's histories. The annual Amache pilgrimage is Saturday, May 19.

Once wiped clean, the site of the Amache Camp in southeastern Colorado is now increasingly home to original and recreated structures. An old shed that was once a recreation hall was recently moved back to the site. It's the first original and joins three new structures, including a guard tower.

For more than 10 years, the Friends of Amache group -- composed of the Amache Historical Society, the Amache Club, the Amache Preservation Society and the Town of Granada -- have dedicated time and effort to restore the site in hopes of sharing the history of Japanese internment and the lessons learned.

'We Lost Everything'

Bob Fuchigami, now 88, and his family would spend three and half years at Camp Amache. But they only had 6 days to get rid of everything and pack only what they could carry. For a young Fuchigami, that included a bag of marbles.

Propaganda films of the era painted rosy pictures of internment, that Japanese-Americans cheerfully filled out forms and left their homes, that government officials gamely helped them work out deals to lease their property. The reality was far different.

The Fuchigami family hastily made an agreement with a local high school teacher to watch over their farm, equipment and vehicles. Included was a clause presenting a very favorable option to buy.

"What are you going to do in 5 days?" Fuchigami said. "He made so much money the first year, he bought it."

"We lost everything."

The windows on the train were closed and the blinds shuttered, with guards nearby insuring the passengers didn't look out. No one had any idea where they were heading during the days-long ride from California to Granada, Colorado. Because there was so little information to go off of, every time the train stop they held their breath. A bathroom break could have become an execution.

More than 7,500 Japanese-Americans were detained at Amache, living on 1 square mile surrounded by barbed-wire fences and guard towers manned by military police. Housing was divided into 29 blocks, with around 250 people per block.

When Fuchigami arrived, his family's small room was bare, spare for a few cots. One light bulb hung from the ceiling. The floor was a single layer of bricks on the sand. There were no private bathrooms, only public latrines with no partitions. Nothing could be farther from home.

Despite the conditions, the internees tried to lead normal lives. They formed social clubs, established a newspaper and stores. Fuchigami joined the Boy Scouts.

Life As An Internee

Years passed. Families expanded and contracted. Officials recorded 412 births and 107 deaths at Amache.

But the signs of their incarceration were undeniably, unforgettably present. Search lights burned from the watch towers at night, guards regularly carried out surprise inspections and they were followed everywhere, even to the restroom.

There was no where to escape. Amache's site was specifically chosen because it was so remote. Temperatures could reach 120 degrees Fahrenheit or hotter. The soil was sandy and loose.

Meanwhile, their internment only reinforced the public prejudices about Japanese-Americans outside the barbed-wire walls.

"We looked like the enemy, even though we weren't the enemy, but the public didn't know," Fuchigami said. "Once they put us into the camps, (the public) thought 'Oh, they must have really done something wrong.'"

One time government officials acquiesced a rare kindness, allowing families to ship in limited amounts of items from back home. Fuchigami's mother quickly ordered a trunk she had left behind, filled with kimonos and other valuables that she had brought over from Japan. But in the time since Fuchigami's family had left, it had been broken into and burgled.

The loss of those heirlooms was the final straw for his mother's health. She suffered from a stroke in the camp.

"She recovered...a little," Fuchigami said.

Home Again, And History Repeating

When the detention order was lifted, but violence and looted homes awaited them. The last group left Amache in October 1945, with a collective $25 in their pockets. A now 15-year-old Fuchigami and his family left on the one-way train.

Fuchigami and his wife Sally now live in a Lakewood retirement home. Bookshelves are lined with books about Amache and family photo albums. One image shows Fuchigami in his naval uniform. He served on the Nelson M. Walker ship in the Korean War.

The irony of serving a country that robbed him of nearly four years of his childhood is not lost on Fuchigami. He recalls a question posed by a black soldier at a talk Fuchigami gave during an event about Amache.

"Why would you join the Navy after the way they treated you?" the soldier asked.

It was a good question, and one Fuchigami had long considered.

"It's the only country I have. It's my country. Just like it's your country. Why would you go off and join the military after the way blacks have been treated?" Fuchigami remembers answering.

"People of color have all been treated badly, whether you're talking about Indians or blacks or Mexicans or Japanese or Chinese or whatever. If you are not white, you get treated differently at different times," he said.

The story of Japanese-American incarceration is as important as ever, Fuchigami said. Today he sees his past being repeated with Muslim-Americans. The chapter isn't closed.