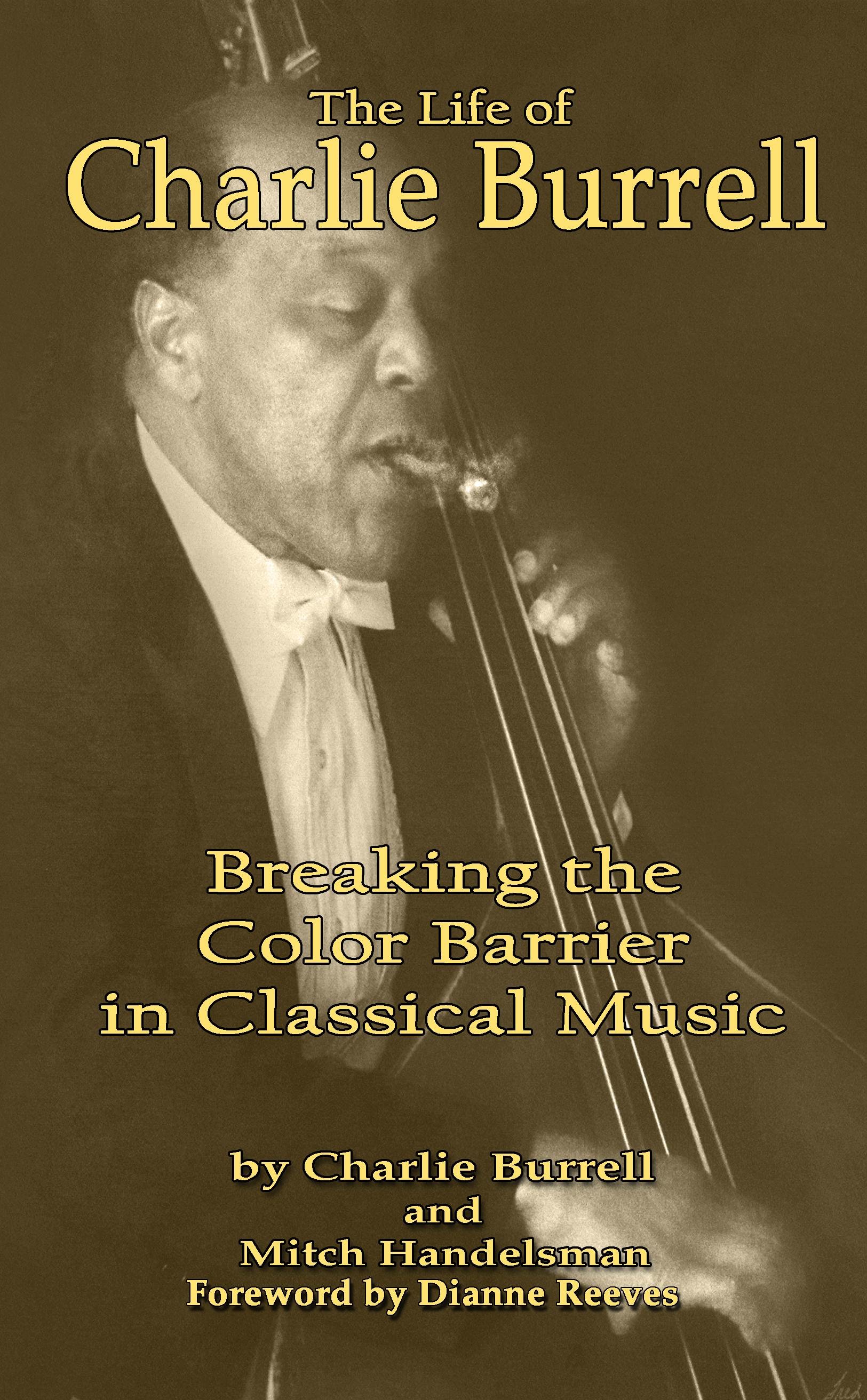

In some circles, Charlie Burrell is known as the Jackie Robinson of classical music. From meager beginnings in Detroit, he traveled to Denver with his bass in tow, looking for his future. Eventually, he found it as one of the first African-American classical musicians in the nation. A new book tells his story.

Behind the scenes as a bassist in the Denver Symphony Orchestra, which dissolved in 1989, Burrell felt differences among himself and his white colleagues. Whites had their own world to go home to in Denver, and African-Americans weren’t welcome, he says. They socialized only at work.

“When I left the hall, that was it,” he said.

He shared that story and others in an interview with “Colorado Matters” in 2006. At the time, he mentioned he had been working on a memoir.

Now Burrell is 94, and “The Life of Charlie Burrell: Breaking the Color Barrier in Classical Music" is being published, co-authored by Mitch Handelsman, a University of Colorado Denver professor of psychology and fellow musician.

Burrell and Handelsman will sign books Saturday, Dec. 6, from 2 to 4 p.m. at the Blair-Caldwell African American Research Library in Denver’s Five Points neighborhood, where Burrell used to perform regularly.

When Burrell came to Denver from Detroit in 1949, he came for the mountains and because had family in town. He brought his resume. He studied music at Cass-Technical School and Wayne State University, both in Detroit, and served in the Navy.

After playing for years in Denver, he joined the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra. He returned to the Denver symphony in the mid 1960s and retired with the Colorado Symphony Orchestra in 1999.

Along the way, he had four kids and married twice. He says there were many years when he struggled with odd jobs, particularly in the early days.

“It was not the easiest thing in the world when jobs were pretty scarce and, in those times, I was only making $65 a week with the symphony,” he said, adding that there were few concerts in Denver at the time.

Some nights he’d play with the symphony and then rush to Denver’s Five Points neighborhood to play in jazz clubs where he was a regular.

He says he was “profoundly happy” playing classical, but he needed jazz, too, and not just for the money. “What kept me sane, was the fact that playing good jazz with people who had no hang ups.

"Symphony musicians were a little strange -- and still are. They have this thing about looking down their nose at everyone else that plays another instrument and that was the exposure I had with them, but with the jazz it was not like that.”