People are causing the Earth's climate to change at historic rates according to a draft of a report recently submitted to the White House.

The report is part of the National Climate Assessment, which is mandated by Congress every four years; it was written by scientists from 13 federal agencies, ranging from NASA to NOAA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Alan Townsend, associate vice chancellor for research at the University of Colorado Boulder, and James White, the former director of the university's Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research and current dean of the university's College of Arts and Sciences, spoke with Colorado Matters about the report and other climate change news.

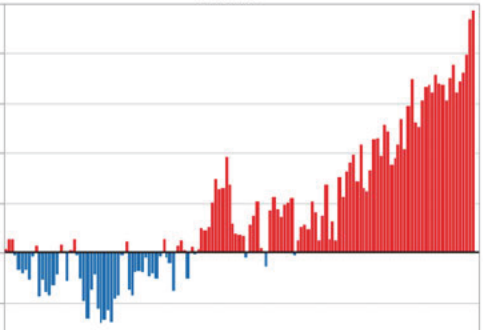

The draft, which was published earlier this month by The New York Times, says the average temperature in the United States has risen rapidly and drastically since 1980, and recent decades have been the warmest of the past 1,500 years. The report also includes a section on the massive floods that hit Colorado in September, 2013, stating that it's difficult to determine whether that event can be directly linked to human-caused climate change.

Over the weekend the White House closed the the panel down. Via The Washington Post:

The Trump administration has decided to disband the federal advisory panel for the National Climate Assessment, a group aimed at helping policymakers and private-sector officials incorporate the government’s climate analysis into long-term planning.

Highlights

On what stands out in the assessment:

Townsend: "Put most simply, it's getting warmer, it's getting warmer faster, the climate is changing, and it's us. We're the ones doing it. The time to respond to that is getting short."

White: "I guess what stands out is what doesn't stand out. This is information that we've known for some time. It's clear that human beings are causing climate change. It's clear that those changes are going to have great economic impacts. They already are having economic impacts. To continue to ignore what's happening really puts us, the country, farther and farther behind both in terms of adapting to these kind of changes and getting out ahead of it and being part of the solution, and benefiting economically from being part of the solution."

Townsend on seeing climate records being broken lately:

"That's a longer list than you probably want to go over on this morning's show. But it makes it very clear that, for example, we've warmed more than a degree globally just in the last few decades. Again, what sticks out that Jim alluded to here is not only is it crystal clear that that warming's occurred, but that really one of the things that the report stresses is there is just no other reasonable explanation behind that warming other than our own activities. Again, Jim put it right, we've known that connection for a long time, and this is just adding more certainty to it."

White on climate change doubters not trusting scientists:

"A whole lot of people here in Colorado have already jumped in their cars and gone north to watch this in Wyoming, and they've done that based on a scientific prediction. We make decisions about what we eat, what we drive, what we take from the doctor, so much of what we do in our daily lives, based on science, the evidence of that science, and the predictions of science. The amount of evidence and the quality and depth and breadth of the predictions within climate change science and climate science is so substantial now that society really should place their trust there too and move towards collectively figuring out what we do about it. You know, Jim alluded to this before. This is no small problem. We ought to be worried and we ought to take it seriously, but we're not yet at the point where we can't come together and think of some really different paths that are also beneficial in other ways. We just need to get past this argument point."

White on why only a few degrees of Earth warming makes a huge difference:

"We know that as you heat up continents they tend to dry out because hotter air evaporates more water and it just gets drier. So we can expect to see more droughts as time goes by, as we have more and more heat energy in the atmosphere. I should point out that the scaling here is important. We've, the planet's gone up in temperature by roughly a degree Celsius. Keep in mind, I think the listeners should keep in mind that the difference between where we were, say, 100 years ago, and a full blown warm planet with dinosaurs roaming on it is only 4 degrees."

Townshend on the need for, and the difficulty in finding, collective will:

"The concern I have around the broader pattern we're seeing, especially of late in this country, although it's not entirely restricted to this country, is that if we're going to come together as a global society, which is what we need to do, and solve an issue like climate change, which is truly a wicked problem in the classic definition. It's hard. It's hard because it requires global cooperation. The climate doesn't care about political parties. It doesn't care about political boundaries. It doesn't care about any of that. It affects us all. And so for us to be effective in finding solutions we have to trust each other, we have to support each other, we have to come together and have a collective will that is frankly lifting everybody up."

Transcript:

Ryan Warner: This is Colorado Matters from CPR News. I'm Ryan Warner. It's sort of like a physical, but in this case the patient getting the checkup is America's climate. From NASA to NOAA, scientists have put together what they call an authoritative assessment of the science of climate change, and their new message is clear. People are changing the climate. We're going to dive into this and other climate news with environmental scientist, Alan Townsend, who's also Vice Chancellor of Research at CU Boulder, and a climatologist, Jim White. He's just become Dean of Arts and Sciences at CU, formerly director of the school's Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research. Gentlemen, welcome back to the program. Jim White: Good morning, Ryan. Alan Townsend: Morning, thank you. RW: The New York Times published a final draft of this report. It is part of the National Climate Assessment. The Trump Administration has yet to comment on it, but over the weekend, the White House decided to disband the panel behind the climate assessment. Alan, when you look at this new report on the state of the country's climate, what stands out to you? AT: Well what I think stands out for me most, Ryan, is just further reinforcement of how clear things are. Put most simply, it's getting warmer, it's getting warmer faster, the climate is changing, and it's us. We're the ones doing it. The time to respond to that is getting short. RW: There is a link to this report at cprnews.org. Again, it's the final draft. I'll say that a spokeswoman for NOAA says disbanding the federal panel "does not impact the completion of the Fourth National Climate Assessments, which remains a key priority." Jim, what stands out to you in this climate report? JW: Well it's, I guess what stands out is what doesn't stand out. This is information that we've known for some time. It's clear that human beings are causing climate change. It's clear that those changes are going to have great economic impacts. They already are having economic impacts. To continue to ignore what's happening really puts us, the country, farther and farther behind both in terms of adapting to these kind of changes and getting out ahead of it and being part of the solution, and benefiting economically from being part of the solution. RW: Alan, in particular, you called out the warming. What does the report have to say about warming in particular? We've seen a lot of records broken lately, haven't we? AT: We have, and that's a longer list than you probably want to go over on this morning's show. But it makes it very clear that, for example, we've warmed more than a degree globally just in the last few decades. Again, what sticks out that Jim alluded to here is not only is it crystal clear that that warming's occurred, but that really one of the things that the report stresses is there is just no other reasonable explanation behind that warming other than our own activities. Again, Jim put it right, we've known that connection for a long time, and this is just adding more certainty to it. RW: Yes, this report says it's extremely likely that human influence has been the dominant cause of warming since the mid-1950s. This report lays out what extremely likely means. There's a helpful little guide. That means 95% to 100% likelihood. Can you lift the veil on something like that a bit for us, Jim? When scientists are able to arrive at language that says extremely likely, what goes into 95% to 100% certainty? JW: I have to chuckle because this is really scientists being scientists. We try to find words to express probability because we think and we work in terms of probability. Let me just take a step back and be a regular, good old human being and tell you that human beings are causing climate change, period. I don't think we need to parse the language. We understand enough about the simple physics behind this problem to know that if you add more greenhouse gases to the atmosphere, you will change climate, and we are changing climate. And that's, it's not something that neither scientists nor politicians should be equivocating about. RW: Given that we're talking about science on the day of the solar eclipse, it seems worth bringing up the eclipse itself and a meme I saw circulating over the weekend, Alan, that said there's very little doubt in the science of eclipses. Why should there be doubt in the science of climate change? Is that an apples to apples comparison to you? JW: No, it's not entirely an apples to apples comparison, but the underlying point there, I think, is really valid. The science of predicting an eclipse is in many ways simpler than the science of predicting all the details of what will happen with climate. Where I think it's important to focus here and remember though is the point here is that society places its trust in decision making, whether that's individual things that we choose to do. People are, a whole lot of people here in Colorado have already jumped in their cars and gone north to watch this in Wyoming, and they've done that based on a scientific prediction. We make decisions about what we eat, what we drive, what we take from the doctor, so much of what we do in our daily lives, based on science, the evidence of that science, and the predictions of science. The amount of evidence and the quality and depth and breadth of the predictions within climate change science and climate science is so substantial now that society really should place their trust there too and move towards collectively figuring out what we do about it. You know, Jim alluded to this before. This is no small problem. We ought to be worried and we ought to take it seriously, but we're not yet at the point where we can't come together and think of some really different paths that are also beneficial in other ways. We just need to get past this argument point. RW: Jim, you mentioned in this new climate report, this big assessment of the nation's climate, the economic impacts in particular. What stood out to you about how climate change could cost the country? JW: Well, change is expensive period. In terms of climate change, I think we need to think in terms of crop yields, where we have drought and where we have rainfall. We're seeing large rainfalls happen more in the Eastern part of the United States, I think it's been like a 70% increase in large rainfalls. And just ponder that for a second. When we build sewer systems and when you flush the toilet and all that stuff, all that infrastructure was designed around a certain amount of fresh water flowing through the system and when that amount of fresh water goes up, the pipes aren't the right size and the sewer systems don't work as well as they should, and that's extraordinarily expensive to fix. Some of the biggest expenses coming down the roads are things like as the oceans begin to rise, or continue to rise, I should say. We have trillions of dollars of real estate and infrastructure along the coasts and we're going to have to figure out a way to move that stuff or abandon it. The Navy alone is spending billions of dollars already raising the docks up because they have to do that. The Navy is sort of stuck wherever the land meets the ocean, that's where the Navy has to be. So this is a, there's a lot of costs that come to this and it's not just the folks who live near the coast. We in Colorado, we pay taxes too. We support the Navy, we support federal flood insurance program, all those things. RW: You're listening to Colorado Matters, I'm Ryan Warner and we check in on climate news occasionally on this program. Joining us this time to talk through some of the headlines, environmental scientist Alan Townsend, who is also Vice Chancellor of Research at CU Boulder, and climatologist Jim White, who formerly directed the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research. Our focus right now is a big new climate report that came out from a slew of government agencies. It's an assessment, essentially, of the country's climate with climate change. When it released the final draft of this report, the New York Times mentioned a rapidly advancing area of research and it's called Attribution Science; finding a link between climate change and specific weather events. This new report does do some of that but, I don't know, I think of the Colorado floods in 2013 for instance, which this report says there is mixed research on in terms of connecting them directly to climate change. How hard is that kind of work, Alan? AT: It's hard. There's a reason that, if you look at climate predictions and you look at some of the general ones, there are some that have been made since way back before even the turn of the 20th century that have still proven to be largely accurate today. The real trick is going from when we heat up this whole global system with a few simple changes to physics, as Jim alluded to, and then ask "Alright well, here was this one event that happened. Was that climate change or not?" That's tricky because that variation in weather is true in our Earth system no matter what. But one of the things we've been able to do both because of the amount of time that we have changed the system already, the amount of, basically, fuel we've put on the fire, plus a development of scientific techniques, a lot of this is about, you know, you'll hear this in a number of realms right now about big data, right? So, techniques where we're able to bring together enormous amounts of data from a lot of different areas and sift through them in very modern, very high resolution ways and ask what the contributions to the patterns in those data are. That's where some of the big advances in this attribution have come from, is being able to look over time, and recent time and ask, alright, how much of that signal that we're seeing seems to be emerging above the background variability and you can put a fingerprint of climate change on it. So in that, for example, we're seeing now really very clear evidence that warm anomalies, so very, very hot days, big heat waves like we saw this summer in the Middle East and Phoenix and a bunch of places. More and more those are clearly bearing the signal of climate change. More and more some of these extreme, high rainfall events are bearing them. It's hard to take any one event and say with absolute certainty it's there, but we're moving in that direction. Again, the thing I would stress is that none of this is inconsistent with what we've thought for, and we've known, for a long time. If you put more of this energy into the system, if you heat up the earth, you're going to see these kinds of things happen. In some ways we shouldn't be asking the question, "Is this one event climate change?" We should be going past the question to which we already know the answer, which is, that we're going to see more of this stuff, how do we get ready for it? How do we deal with it? RW: Do you think, in a way, that that is the wrong question to be asking, it's a bigger question that should be asked, this has also been called hindcasting, and I'll say that a paper from July that appeared in Weather and Climate Extremes found that the Colorado 2013 floods were worse because of human caused climate change. I think it's interesting you bring up this idea of variation, because I think we all think of the weather as varying. You're saying the variation is getting more intense. In a few places in this report it says that the Dust Bowl of the 1930s remains the benchmark for drought and extreme heat in the US. So Jim, what would you say to someone who says, "Look at that. See, it's been much worse." Put the variation into some context for us. JW: I think that comparing these droughts is really not the approach we should be taking. I agree with Alan that sometimes you've got to take a step back and ask, "Are we asking the right questions?" We know that as you heat up continents they tend to dry out because hotter air evaporates more water and it just gets drier. So we can expect to see more droughts as time goes by, as we have more and more heat energy in the atmosphere. I should point out that the scaling here is important. We've, the planet's gone up in temperature by roughly a degree Celsius. Keep in mind, I think the listeners should keep in mind that the difference between where we were, say, 100 years ago, and a full blown warm planet with dinosaurs roaming on it is only 4 degrees. RW: Oh wow. JW: We're a quarter of the way there already. We have 400 parts per million CO2 in the atmosphere. We haven't seen those levels for three to five million years. So in a sense, and this is what Alan was getting to, in a very real sense, all the weather systems we see today, all the climate we see today, is impacted by human beings because we're the ones that added that CO2 to the atmosphere. Attributing single events, yeah, okay, that's a slippery slope, but attributing a collection of events like 70% more big rain falls in Eastern United States, easy. Yes. Human beings. RW: Alan, you make an unexpected link between the deadly rally in Charlottesville, Virginia and how the nation deals with climate change. That might seem to some an unconnected issue. What is the connection you see? AT: Yeah, well, let me first say on that, Ryan, that before we get into that connection that what happened in Charlottesville and the broader pattern we're seeing of divisiveness, of sowing the seeds of hate is just utterly reprehensible. There should be no place for that anywhere in global society and that's the most immediate issue on our plate. That is fundamentally important on basic human moral ethical terms. The concern I have around the broader pattern we're seeing, especially of late in this country, although it's not entirely restricted to this country, is that if we're going to come together as a global society, which is what we need to do, and solve an issue like climate change, which is truly a wicked problem in the classic definition. It's hard. It's hard because it requires global cooperation. The climate doesn't care about political parties. It doesn't care about political boundaries. It doesn't care about any of that. It affects us all. And so for us to be effective in finding solutions we have to trust each other, we have to support each other, we have to come together and have a collective will that is frankly lifting everybody up. And so when we see not only individuals but even leaders pushing forward approaches that are sowing divisiveness and sowing difference, that works directly against our ability to solve any major societal challenge in front of us, and this is one of the big ones that we face. RW: So it's just a question of solving world peace and then we can solve climate change? AT: Yeah, we'll get that done by next week. JW: Actually, climate change is a little easier. RW: I'd like to wrap up as we often do with glimmers of hope. I think we have time for just yours, Jim White. What are you seeing in the science, in the news today, that gives you hope in the face of climate change? JW: Just riffing off what Alan said, what gives me the greatest hope is that the solutions for sustainability, the solutions for climate change are really things like we need to treat each other better. I'll give an example. Population is a core problem that we have to deal with. The more people we have, the more impact we have. The key to population control is the empowerment of women and what I see today around the world is greater and greater empowerment of women. As they grow in economic power, as they grow in social power, they have fewer children per woman. That's something that the demographers tell us. In other words, I think the keys to success in the future really lie in us being better people; better to women, better to minorities, better to each other. I know that sounds really, actually that sounds very Boulder doesn't it? It is true. I think that that should give us all a lot of comfort. RW: I want to thank you both. You heard Climatologist Jim White, who recently became CU's Dean of Arts and Sciences and Environmental Scientist, Alan Townsend, Vice Chancellor for Research at CU Boulder. When we come back, what you learn when you spend a decade photographing ranchers in Colorado. This is Colorado Matters from CPR News. |