But after Saigon fell, the communists took almost everything from the family -- a fate that befell most professionals in Vietnam after 1975. Chung’s family moved to a farm that had no running water or electricity. It was there that Vinh Chung was born, followed by twin brothers 18 months later.

In 1979, near starvation and seeing no good prospects for their children, Chung’s parents decided to join the boat people fleeing the country. “They didn’t know their final destination… or even if they would survive,” Chung says.

The chance of death was nearly as great as that for a new life. Refugees fleeing Vietnam across the vast sea could encounter Thai pirates, who not only stole refugees’ valuables but often raped women and killed their victims. And if people made it safely across the ocean, by the late 1970s neighboring countries had been so overwhelmed by refugees that most had shut their doors to new arrivals.

Chung tells a tale of pirate attacks; being beaten and led on forced marches by the Malaysian Navy; and finally cut adrift in the middle of the South China Sea without water or food. At one point, some parents were so grief-stricken at seeing their children dying of dehydration that they considered drowning them.

Vinh Chung spoke with CPR’s Elaine Grant.

Read a chapter from his memoir below.

Book Excerpt: "Where the Wind Leads"

It isn’t clear who first decided that my family should leave Vietnam.

It may have been Grandmother Chung when she realized that her “farming empire” was never going to amount to more than ten acres, or when she recognized that her hidden gold and diamonds would have no value in the new Vietnam. As long as the communists prevented her from spending them, they were worthless.

It may have been my uncle who first decided we should leave because he didn’t even have ten acres where he could stretch his legs. He was confined to a small house with his wife and six kids and no business enterprise to give him an excuse to leave each morning. Even worse, he was trapped in a small house with my grandmother, and at close range flying objects seldom miss.

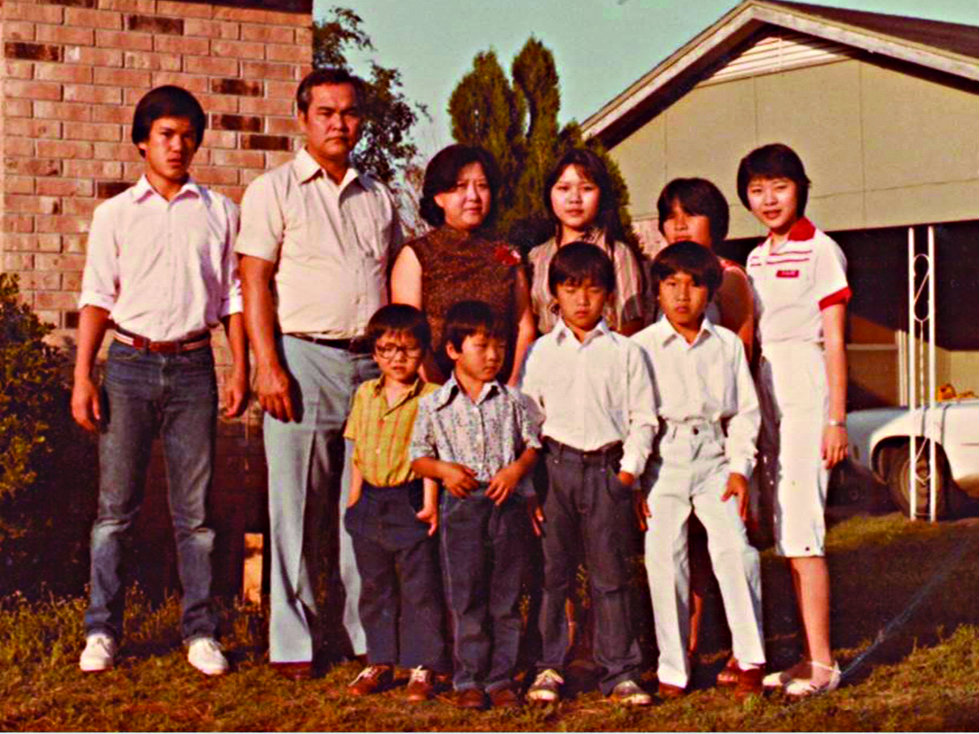

Or it might have been my mother. By the end of 1977, she had born eight children, including newborn twin boys. She breastfed each of us as long as she possibly could—a necessity on a small farm with barely enough food to go around—but her own restricted diet made it difficult for her to produce enough milk to feed two hungry boys. The possibility of starvation was beginning to loom large, not just for her babies but for all of us. Almost as terrible to her was the stark realization that her children had no future in Vietnam. Our education would be severely limited, and she knew from her own hard experience that limited education meant limited opportunity. Her greatest fear was that her children would be forced to accept what she considered the lowest of all jobs: herders of water buffalo. To my mother that was the worst possible fate, and she was determined that her children would do better.

It definitely wasn’t my father who decided to leave, and it wasn’t because he disagreed with his wife or didn’t care about us. My father grew up in an predictable environment where circumstances and even life itself could change overnight. That kind of unstable environment can affect different people in different ways; the effect it had on my father was to cause him to fear change—any change, even if it brought the possibility of improving his lot in life. There is an old Chinese proverb that says, “Better the devil you know than the devil you don’t,” and that perfectly captures my father’s fearful mindset. It wasn’t that he wanted to stay in Vietnam; he just didn’t want to leave.

In a sense the decision to leave Vietnam was made for us. My ancestors were part of more than a million Chinese who migrated to Vietnam from the southern provinces of China in the late nineteenth century. The Chinese are a very cohesive people, which is why in cities all over the world, there are large communities of Chinese living and working together. In New York and San Francisco they are called Chinatown; in Saigon it is known as Cholon. The Chinese place a high value on discipline and hard work and as a result tend to be very successful in business. The Chinese who chose to settle in North Vietnam became farmers, fishermen, coal miners, and small merchants, but in South Vietnam they were more ambitious and quickly came to control the rice trade, transportation, banking, and insurance. My family was extremely successful in business, but among the Chinese we were not the exception.

When the communists took over South Vietnam, their anger was directed at everyone who had been rich or powerful in the former regime, regardless of ethnic group. Vietnamese, Chinese, Cambodian, Thai—it didn’t matter. If you were rich, you were part of the property-owning bourgeoisie who had been oppressing the poor working class, and you were about to feel the wrath of the proletariat.

In the late 1970s, my parents began to sense that the government’s attitude toward the Chinese was changing. Vietnam shares a northern border with China, and there was a growing conflict between the two nations that became so hostile that they briefly went to war. As hostility increased with China, Vietnam grew more and more suspicious of its own Chinese citizens because they feared that the Chinese might be more loyal to their ancestral homeland than they were to Vietnam. Fear began to erupt into violence, and in Cholon, Saigon’s Chinatown, houses were searched, money and property seized, and businesses shut down. The Chinese living in northern Vietnam sensed the growing hostility, and so many began to flee across the border into China that China was forced to close its borders to its own people.

Because my parents had been exiled to a small farm, they were more or less insulated from the growing hostility, but we could see the handwriting on the wall. We had been spared the wrath of the proletariat, but we understood that our sentence was more of a parole than a pardon. When we began to sense that public sentiment was about to turn against us, we decided to leave before it happened. There was a saying among the Chinese in those days: “If streetlamps had legs, they would have tried to escape as well.”

And the government was willing to let us go—for a price. Since the fall of South Vietnam more than 130,000 refugees had fled to other countries, which made the refugee business extremely profitable for the government. With so many people wanting to flee the country, the government realized they had only two options: they could either try to prevent everyone from leaving, which would have been a violent and expensive business, or they could allow them to leave but administrate the process—and bureaucracy is something communists do very well.

When the Chung family first gathered to discuss the idea of leaving Vietnam, my uncle suggested that the most practical option would be for some of us to leave while some remained behind; a smaller party would make planning easier and reduce the overall cost. His suggestion might sound a bit cold and calculating, but splitting up was a common practice among Vietnamese refugees because leaving the country was extremely expensive and always dangerous. Instead of an entire family leaving at once, someone, usually a father or an oldest son, would leave first and find a job; when he had earned enough money he would send for the rest of his family to join him. That was the theory, anyway, but it often did not work that way. Families were often separated for years, and because of the dangers involved many of those fathers and sons were never heard from again.

Since my immediate family was the largest, it was suggested that we should be the ones to split up, leaving the younger children behind—especially the twins. The journey might be too rough for them, it was suggested, and a pair of eighteen-month-old boys would be too much of an annoyance and possibly even a danger to the rest of the group. When that suggestion was made, my mother put her foot down. She made it very clear to everyone involved that there were two nonnegotiables: our whole family was going to stay together, and our whole family was going to leave Vietnam—end of discussion.

Once it was understood that everyone in our family would be leaving, planning could begin in earnest. My uncle, along with another man named Mr. Hong, spearheaded the effort; it was a role that suited my uncle well because his prior job as director of sales for Peace, Unity, Profit had made him very good at making connections and negotiating deals.

There were two basic ways that my family could leave the country—by land or by sea—and each had its benefits and risks. At first glance a land route seemed easier and safer because no one in my family had ever been on a boat before or had even seen the ocean. But the northern border into China was closed, and land routes to the west would force us to pass through the killing fields of Cambodia or the minefields of Laos. Even if a safe land route could be found, the distance we would have had to travel would have been staggering, and most of it would have to be done on foot—not a pleasant prospect for a family with eight children under the age of twelve.

It was quickly decided that our best option was to leave by sea, but that meant we would have to obtain a boat, and in Vietnam boats were in short supply because almost every seaworthy vessel in the south had already been taken by earlier refugees. It would have been much too expensive and time consuming to construct a boat, so an existing boat would have to be found that could be patched up and made seaworthy.

My uncle and Mr. Hong made contact with the Public Security Bureau, a department of the Ministry of Interior that was responsible for overseeing all would-be refugees. The two men quickly discovered that the process of leaving Vietnam was going to be complicated and extremely expensive, and like many things run by the government, it was also corrupt. Even to begin the process there was a “registration fee” of two taels of gold per person, the equivalent of about $2,700 per person in today’s dollars (the tael is an Asian unit of measure equivalent to about 1.2 ounces). The total fee would amount to eight taels of gold per adult, four per child between the ages of five and fifteen, and children under five traveled free—what a bargain. The government even controlled the sale of all boats and gasoline; at every step of the departure process, the government had figured a way to take a cut.

My uncle did the math and realized that the cost for my extended family to legally leave Vietnam would be almost a quarter of a million dollars. Fifty percent of the money would go directly to the government, forty percent would cover the cost of the boat and fuel, and the remaining ten percent traditionally went to a professional organizer or to pay bribes—and everyone had his hand out.

The government’s final requirement was that at the time of departure all refugees had to sign a document turning over all of their property and possessions to the government and waiving any future claim. That made leaving an irreversible decision; it meant that my family would not be able to rent out the farm just in case we had second thoughts or if the voyage turned out to be too difficult. When we left Vietnam, we would be leaving for good, and if we changed our minds, there would be nothing to return to.

My uncle decided that if we included more people in our party, we would be able to afford a larger boat. That was more than a financial decision; a larger boat would be safer because a small boat had a much greater chance of being capsized or swallowed by rough seas. He began to search for other refugees who might be willing to join us by making discreet inquiries through trusted family connections like distant cousins, family acquaintances, and friends of friends. By the time he was finished our little family outing had expanded to an exodus of 290 people and included sixteen different families.

At any point in the departure process, some government official could ask for a bribe, and if he did, we would have no recourse but to pay him whatever he demanded. Professional organizers were notoriously corrupt. Every additional refugee meant more profit, so at the last moment before a boat’s departure an organizer often showed up on the dock with several additional passengers, and the current passengers would have no choice but to take them aboard even when the additional passengers overloaded the boat and made it dangerous for travel. The refugee was never in control of his fate, and potential dangers were at every step of the journey. Old and unreliable boat engines could break down at any moment, inexperienced captains had never steered anything larger than a river barge, and incompetent navigators had nothing but a compass to navigate by.

Finding a salvageable boat, repairing it, and making all the other necessary arrangements should have required at least six to eight months to complete, but two events occurred that shifted the project into high gear: in the middle of 1978, devastating storms and floods made the struggling Vietnamese economy even worse than it already was, and in February 1979, Vietnam went to war with China. When that happened Vietnam’s Chinese citizens became Vietnam’s enemies, and the government began an organized campaign to eject as many ethnic Chinese from the country as possible. That is when my family knew that it was really time to go.

The soonest we could be ready to leave was June, and we did not dare leave later: June marked the beginning of the typhoon season in the South China Sea, and even the big commercial ships did not risk crossing in a typhoon. A departure date was chosen—June 12—and we hurried to make the final arrangements.

It was around that time that my mother had a dream.

In the West we are too sophisticated to pay much attention to dreams anymore. Psychiatrists are about the only people left who seriously entertain the idea that a dream could have a deeper meaning, but in the rest of the world it is different. In most countries people take dreams very seriously, and they are willing to consider the possibility that sometimes a dream could be more than a dream—it might be a message.

One night my mother dreamed that she was in the marketplace in Soc Trang along with our entire family. Grandmother Chung wasn’t there—it was a dream, not a nightmare—nor was my uncle or his family. It was just the ten of us: my mother, my father, and the eight children. The market was noisy and crowded with people from all over town, talking, haggling with vendors, calling to one another across the square.

Suddenly everyone fell over dead.

My father and all eight of us children—we were dead too. Even my mother was dead though, in the manner of dreams, she was still conscious, and her eyes were open. At the far corner of the market, she saw a solitary standing figure: a man dressed in a white robe with long brown hair and a beard to match. As my mother watched, unable to move a muscle, the man began to make his way across the market toward her, stopping from time to time to point down at one of the reclining bodies—and whomever he pointed to, that person came back to life and stood up.

My mother began to fervently pray that the man would point to her, too, and sure enough, when the man finally stood over her, he pointed to her, and my mother rose to her feet. She was ecstatic—until she remembered that her husband and children were still lying dead. She didn’t dare speak to the man, but she began to pray again, this time that he would extend the same kindness to her entire family and bring them back to life too.

And he did. As he pointed to each of us, we rose to our feet until our whole family stood alive and well again.

That is where the dream ended.

But my mother wanted to know what the dream meant. For some reason this dream seemed different to her—so vivid, so powerful, so suggestive of some deeper meaning. She began to ask her friends to help her understand the dream, and they offered different interpretations.

“That was the Buddha,” one of them said. “He was appearing to you, trying to tell you something.”

“The Buddha is bald and fat,” my mother replied. “This man looked nothing like that.”

“It was one of your ancestors trying to communicate with you,” another friend suggested.

But my mother shook her head. “None of my ancestors ever looked like that.”

And that is where it ended. No one was able to interpret her dream, so my mother simply filed it away as one of those unexplained mysteries of life.

Besides, she had more important things to worry about.

Leaving the land of their birth was no longer just an intriguing idea that our family discussed in whispers behind closed doors—it would soon be a reality. We were actually leaving Vietnam, and there would be no turning back. My mother remembered that dark day of despair when she almost threw herself into the Bay Sao River with Jenny in her arms; now she was about to cast her entire family into an ocean, and the prospect terrified her. She had heard the radio broadcasts from the Voice of America, Voice of Australia, and the BBC warning potential refugees about the extreme peril; she had heard the stories about the refugees who did not make it, the ones who died of thirst or sank into the sea or just disappeared without a trace. Would her family be among them? Was it really better to die than to live in communist Vietnam? Would her family have enough food, enough water for the voyage? And if they survived the voyage, where in the world would they live?

Little did my mother know that half a world away, someone else had been asking the very same questions.