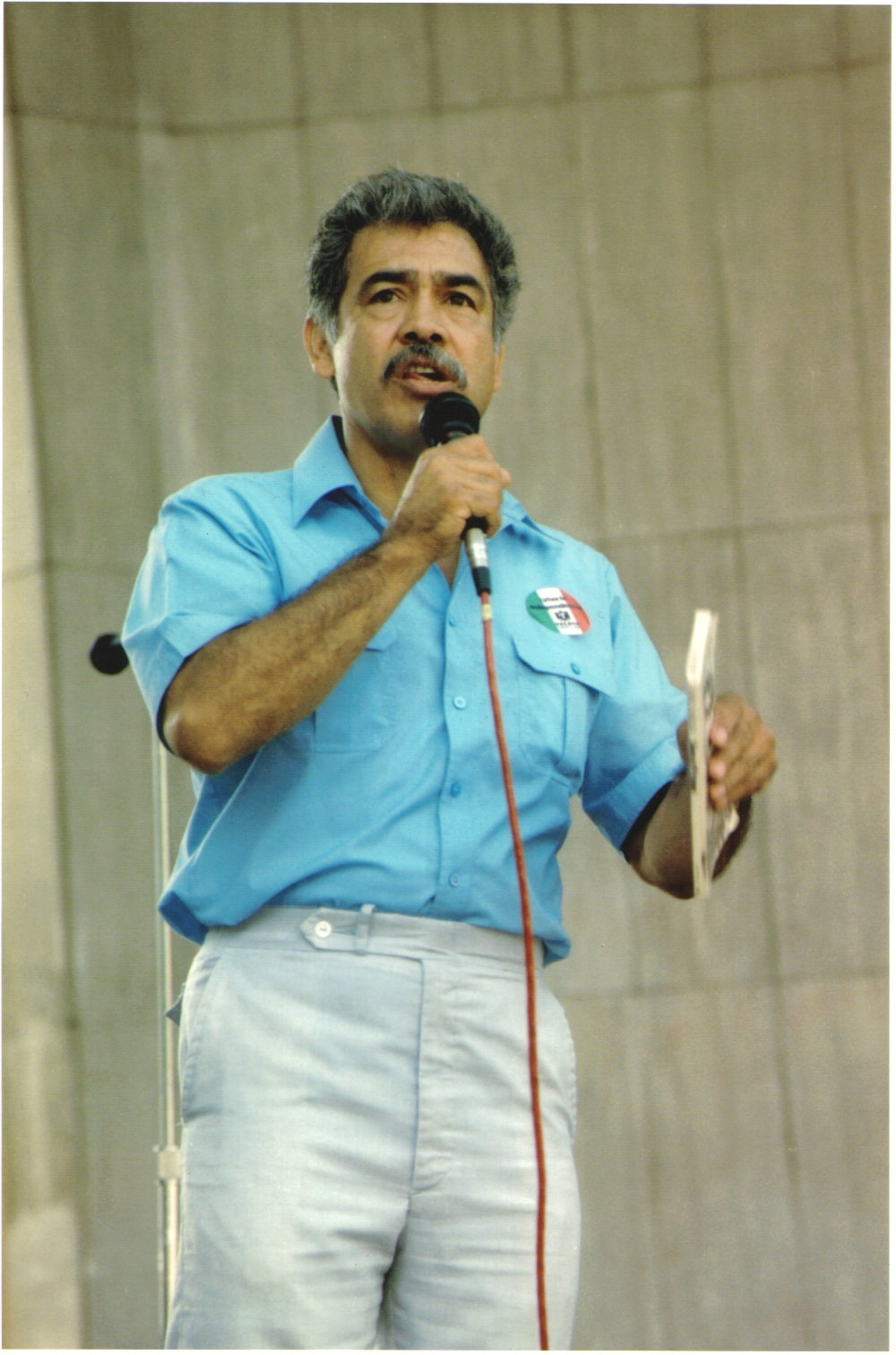

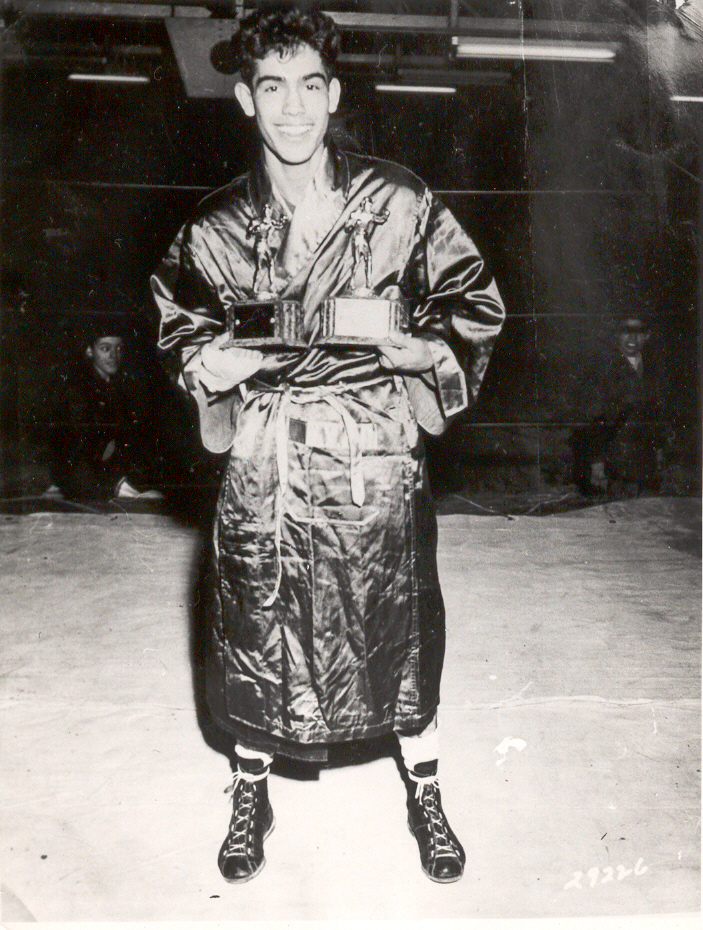

In some ways, Rodolfo "Corky" Gonzales was an unlikely leader of the Chicano movement in Colorado. He was a college dropout and a Golden Gloves boxer.

In some ways, Rodolfo "Corky" Gonzales was an unlikely leader of the Chicano movement in Colorado. He was a college dropout and a Golden Gloves boxer.

But Gonzales was also drawn to books. They fueled his writing and speeches, which inspired countless people in the era of Denver's Crusade for Justice, part of the Chicano "Movimiento" of the 1960s and 1970s.

Given Gonzales' love for the written word, it seems fitting that a new branch library on Denver's Irving Street, just off West Colfax Avenue, bears his name. The branch opened Feb. 28. But what would he have thought about that?

"He would have protested first and said, 'Um, hmm...,'" says his eldest daughter, Nita Gonzales. "He never wanted that."

Nita Gonzales has followed in her father's footsteps as a community activist. She has been recognized as a White House Champion of Change, and now runs a school her father helped found, Escuela Tlatelolco, a nationally recognized model for Chicano, Mexicano, and indigenous education in Denver.

Public comments solicited by the Library Commission overwhelming supported Gonzales' name for the branch, though the process also re-ignited an old conflict. Among the several people who expressed opposition to naming the library for Gonzales was David O’Shea-Dawkins, a retired Denver police sergeant. He recalled being injured during a shootout in 1973. He claims that Gonzales had a legacy of supporting people who resorted to violence.

"Unless history is to be rewritten, Rodolfo Gonzales was not the champion of the rights of Hispanics," O'Shea-Dawkins wrote. "In the final analysis his leadership was divisive and his cabal of youthful bullies intimidated anyone who would not agree with their methods. His righteous beginnings were a wasted opportunity after he chose to support violence to reach his goals."

O'Shea-Dawkins could not be reached for comment. Accounts of the March 17, 1973, shootout he referenced are contested by Gonzales' supporters. In incident involved officers, an explosion at a Crusade for Justice Office near East Colfax Avenue and Downing Street in Denver, and the death of activist Luis Jr. Martinez. Read O'Shea-Dawkins' account here, reprinted by The Denver Post.

Nita Gonzales responding to the retired police sergeant's letter to the Library Commission

"That, to me, is hogwash. You're talking about police interaction with community now? It was 10 times worse then. And when you talk about violence, I will tell you this: Not once in any rally, in any march, in any time I was with my father, did he advocate us to be violent.

"We always were taught to defend ourselves. I will not deny that, but we were living in a time when you all should remember as well where students at Kent [State] were shot down; where people in the South disappeared and were killed and murdered for standing up. This was not at the hands of those people nor here in Denver did the Crusade ever, at its rallies, at its marches, advocate that, but we did defend our people.

"What [the retired police sergeant] is talking about is March 17, 1973, and what I recall is that our building was blown up and Luis Jr. Martinez was left dead. I'm sorry. That's hogwash in my mind. I absolutely would suggest, no, encourage people: learn the history of that time. And here we are now, in 2015, still dealing with this kind of interaction with police and community."

On her father's popular poem, "Yo soy Joaquín" ("I Am Joaquín")

"I think you need to understand that in that time, in his time, in his era, where was he ever going to learn about who he was? How would he ever be able to read or hear someone talk about his people's history, their contributions? You couldn't find that anywhere.

"He was like an archaeologist. He was out there kind of digging and trying to find this history, this truth, this place that people need to have in the world. And so, the poem was the end result of this digging -- of his dig, his historical cultural-political dig. And it also was a way for him to give voice to, 'We maybe look this way or are known this way, but we are this.'

"It was also awakening for him around that indigenous part of who we are because you recognize that in that time more people were embarrassed and shamed to be anything but maybe Spaniard or Spanish-American -- definitely not Mexican. That was lower. And then, oh, definitely not indigenous. And that was on both sides of the border and he wanted to speak out against that because that's exactly who we were. So he was trying to give us a sense of pride, a sense of place, a sense of geography, a sense of history that until that time we had no knowledge of and clearly wouldn't read in any school history books."

On what her father would say about a library named for him

"Mayors and other individuals had asked him about that -- a park or a street or something. And that's not something he wanted or aspired to. But I think this place, because of what it is, what it allows -- it's open, it's free to the public, it's where no matter what your income status is you can go in and you can use computers and you can read and you can have story time. He would have been humbled by that, I believe."