In Denver in the 1890s, thousands would line up to see a man they believed could heal them with his touch. Francis Schlatter, who was described as having Christlike qualities, gained national and international attention for his healing abilities.

Schlatter eventually orchestrated his own disappearance, only to be presumed dead and then possibly resurface.

David Wetzel traces Schlatter's life in his new book "Vanishing Messiah." Wetzel spoke with Andrea Dukakis.

Read an excerpt:

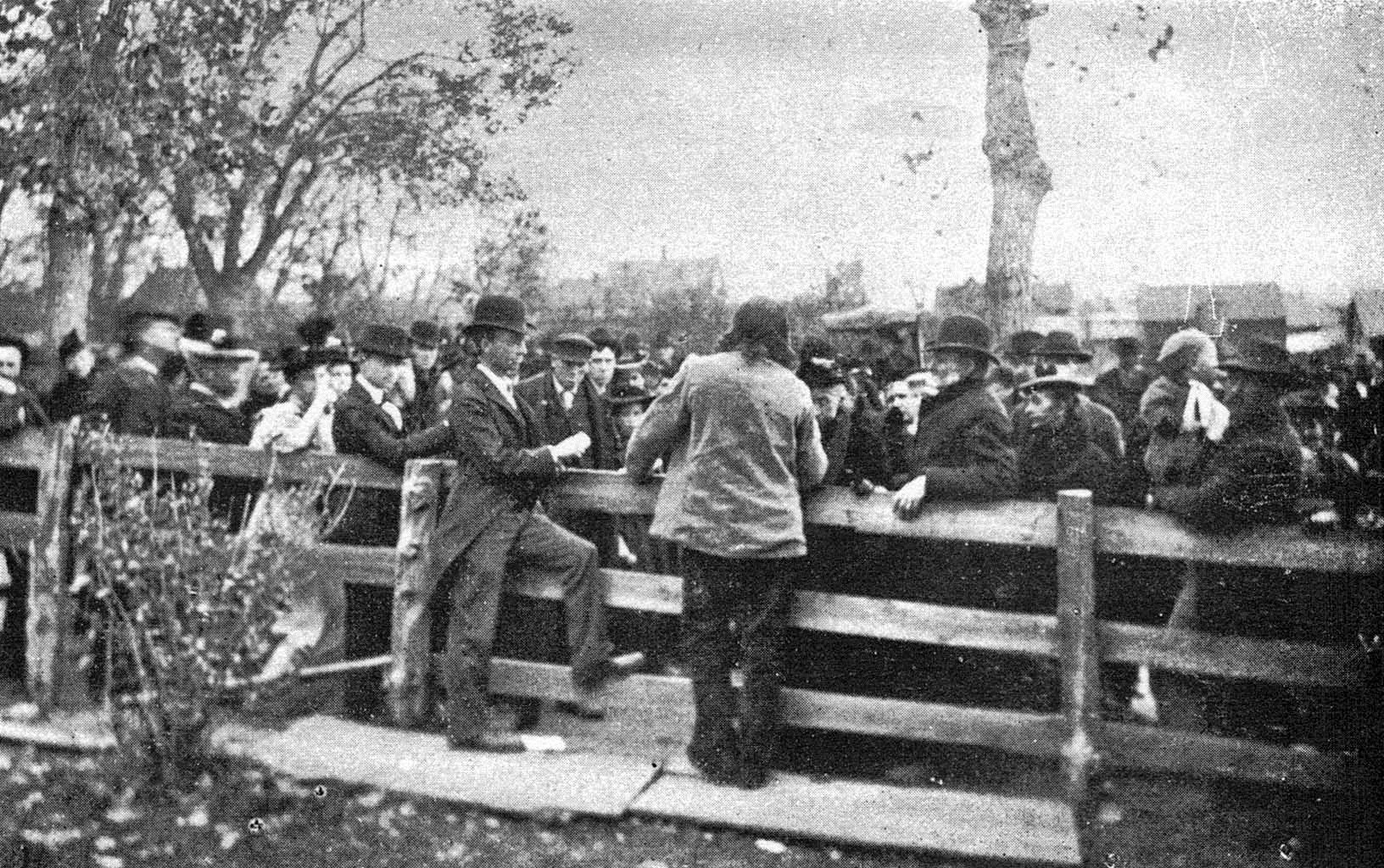

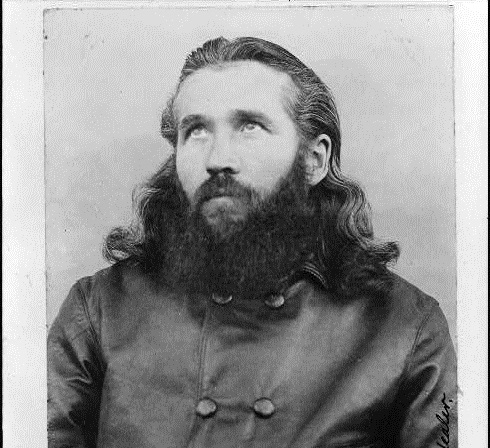

Schlatter was more than a healer. With his long, shoulder-length hair, rich beard, and clear blue eyes, he evoked the image of Jesus Christ. More than that, his humility, generosity, and temperament embodied all the virtues of Christ, and he asked for nothing in return for his healing work. “I have no use for money,” he said. When someone insisted on paying him, Schlatter quickly turned the coins over to a poor bystander. It was said that he brought back a small child from death twice, only to lose it a third time. Schlatter treated everyone—no matter their race, nationality, or station in life. He took no credit for healing them, for it was the Father—the word he always used for God—who did so. Nor did he ask for a confession of faith or doctrinal creed, only that sufferers believe that the Father would heal them. But he acknowledged being the divine instrument through which they were healed, and when anyone asked him if he were the Christ, Schlatter said “Yes.” By the time he began healing in Denver, in mid-September 1895, his fame had traveled across the country, buoyed by curious reporters whose news stories reverberated along the wire services. Mail poured into the post office, some of it addressed simply, “The Messiah, Denver, Colorado,” and Schlatter tried to answer every letter—for he believed that anything he touched would have the same healing effect as his own hands upon a sick or suffering pilgrim. When he touched each person who stood before him, he raised his head and said, “Thank you, Father.” He took each person by the hands and squeezed tightly, even small children—who never cried out in pain. Every day Schlatter stood behind the picket fence, bareheaded in the sun or rain, and treated the line of sufferers while bystanders filled the street, standing among carriages in which the infirm or disabled waited for the healer to visit them at the day’s end. Vendors set up tents here and there to sell sandwiches, popcorn, watermelon, and lemonade. The scene was part carnival, part worship service, but over all a sense of quiet expectation and hope filled the air. As October passed into November, the crowd numbers grew. The healing sessions would not last forever, and there was rumor that Schlatter would take his ministry to Chicago [very soon]. Newspapers repeated the date of his scheduled departure, and trains brought hundreds of anxious pilgrims into Denver from around the West and Midwest. The healer spent less time with each person—down from a half a minute to just a few seconds. The ministry seemed to be building to a crescendo, for many who had scraped money to come to Denver did so because Chicago was out of the question. And then he was suddenly gone. Reprinted from The Vanishing Messiah: The Life & Resurrections of Francis Schlatter by David N. Wetzel with permission of University of Iowa Press. Copyright (c) David Wetzel, 2016. |