While the Front Range economy booms, there's increasing frustration among people who are priced out and pushed out of Denver. They don't think the city is doing enough to fight gentrification and the displacement that comes with it, and a new grassroots movement is emerging to take up the challenge.

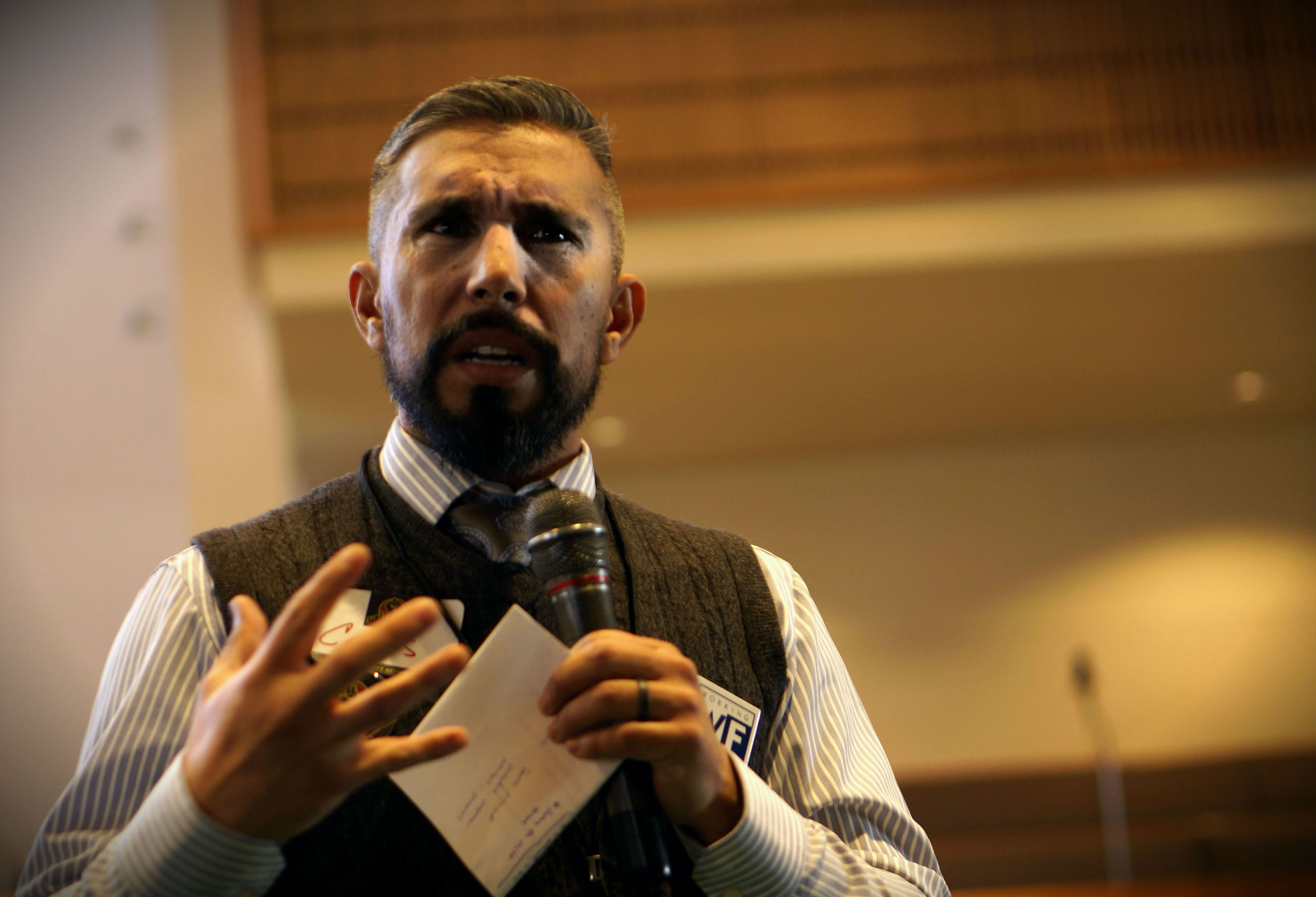

“What we’re seeing all of this boil down to: community control and community ownership of not just our land and our homes, but resources and business,” said Candi CdeBaca, part of the Denver Community Action Network. “That’s the only way that we will create a buffer for ourselves to help us really kind of navigate market forces acting upon us.”

CdeBaca lives in the Swansea neighborhood in northeast Denver. She’s seen it change dramatically, so much so that she’s running for a city council seat. She was one of hundreds who talked about a path forward at one of Denver's oldest black churches, Shorter Community AME, which hosted the “Gentrification Summit: Our Communities Are Not For Sale.”

The gentrification issue really reached a boiling point in November when ink! Coffee in northeast Denver posted a sign that said, “Happily gentrifying the neighborhood since 2014.” The shop is on Larimer Street in the heart of Five Points, which many consider to be the old heart of Denver’s African American community. There’s been a lot of upscale development there — and displacement.

The ink! moment sparked protests. The coffee chain apologized. But it was a real catalyst, said Lisa Calderón, co-chair of the Colorado Latino Forum and one of the organizers of the summit. There’s a sense of powerlessness when it comes to this issue in Denver, and many cities around the country.

“We have seen those types of offensive ads before and we’ve said things,” said Calderón. “But I think individually we’ve said them. There was never really a spark point. I also think because [of] social media it’s easy to connect a lot faster.”

There are market forces at play. People want to live in the city, demand which in turn raises prices. And longtime residents, especially renters, find their living situations in jeopardy. For some of those concerned about the trend, it goes beyond economics.

Shorter AME’s Rev. Timothy Tyler put it this way: “Whenever you have an organized plan to destroy historical communities and to drive out ordinary people in the name of progress. That’s a social justice issue.”

“We are here this morning because for too long we have grumbled and complained among ourselves. But we have not had the public discussion about how we live constructively and humanely with each other without trying to destroy each other’s past, present or future,” he said to those gathered.

His speech really set the tone for the whole day. Many there said they feel disenfranchised by their political leaders, that politicians have favored developers and left others behind. Some speakers at the summit said they believe the I-70 expansion project, the urban camping ban and the redevelopment of the National Western Complex in northeast Denver are designed to get rid of certain people while attracting others.

Tay Anderson, the 19-year-old who ran for Denver school board during the off-year election, was among those at the summit. He's been very critical of Mayor Michael Hancock and City Council President Albus Brooks, who represents the district where ink! Coffee is located.

“We are here to tell politicians that if you do not represent us, if you will not listen to our voices, if you will just kick us out because you have a nice check from a developer, or because 90 percent of your contributions are from developers, then let me do you a favor. In 2019, we’re gonna un-elect you and we’re gonna elect people that will represent your values,” he said.

Mayor Hancock had an indirect response to that criticism in a Facebook Live forum — a dueling event held earlier in the week — that also addressed gentrification

“I have never sat down at a table where we're planning the redevelopment of the stock show or we're planning investments in Five Points and said, ‘This is just for the new people coming to Denver,’” the mayor said.

The mayor did not attend the summit at Shorter AME. But he did sent several staffers “to listen to community members concerns and collect ideas,” and his office released the following statement: “We know this is a challenging issue that is impacting our longtime residents and we will continue to listen and work to make Denver affordable for our families.”

There were probably close to a dozen elected officials at the summit. And maybe a dozen candidates showed up.

“I think that we have some special responsibility as elected officials in this topic. And so I’m here for both inspiration, motivation, and ideas and to just for the community to even know that I’m seeing them and hearing them,” said At-Large City Council member Robin Kneich.

She said she’d like to see a broader effort that takes a closer look at wages as well as housing.

Responsibility for gentrification wasn't entirely placed at the steps of city hall. The organizers looked at gentrification through many lenses, not just housing that’s affordable and attainable. Issues with the criminal justice system and cultural preservation also came into focus, including a breakout sessions that theorized that mass incarceration contributes to gentrification and how to create and foster socially responsible businesses.

“We can structure companies that lift employees up through corporate structures that are collaborative, through social enterprise, through profit sharing,” said Denver entrepreneur Kayvan Khalatbari. “We can invest in our local economies by buying locally and hiring the people in the neighborhoods in which we operate.”

Khalatbari is behind metro Denver businesses including Sexy Pizza and Birdy magazine. He’s also running for mayor in 2019. Khalabari said everyone should take responsibility for helping solve gentrification. That means, as a consumer, he said, spend money thoughtfully and intentionally in support of local businesses.

At one point, folks at the gentrification summit were asked to take out their phones and email their city leaders. There was also a lot of talk about creating some kind of unified calendar to help people know when, where and how they can attend public meetings.

Even though many of these activists can be vocal, they don’t consider themselves anti-development or anti-growth.

“It’s not that we’re not asking for new people to come into the community, and particularly business owners,” said Calderon. “We’re just asking that it be thoughtful, integrating into the community, paying attention to the culture. We’re also saying, ‘Hey if you’re going to start your business in our community, hire locally.’”