Last summer, in southern Iceland, the flanks of the volcano Bardarbunga ripped open and began spouting fire. Fountains of lava soared skyward and molten rock oozed downhill, toward the sea. The volcano has continued to pump gases into the atmosphere since then and scientists are watching it with concern.

The Icelandic volcano Laki erupted in 1783 and spewed out ash and fog for eight long months. Sunless days affected harvests. The aftermath caused the deaths of a hundreds of thousands of Europeans and northern Africans and a famine was so brutal that it was said to have contributed to the start of the French Revolution in 1789 and a bitterly cold winter in the United States.

In the book, “Island of Fire: The Extraordinary Story of a Forgotten Volcano That Changed the World,” Colorado authors Alexandra Witze and Jeff Kanipe tell the riveting story of Laki’s eruption and its impacts across the world. It’s a drama told through the eyes of the clergyman and self-taught naturalist Jón Steingrímsson who kept detailed records of the eruption and its aftermath.

Weaved into the narrative are scientific and historical details of other deadly volcanoes such as the 1815 eruption of Tambora, which sparked such a wet, dark summer, that Mary Shelley stayed inside her house and wrote “Frankenstein.” Witze and Kanipe’s book adds context to the 2010 eruption of Eyjafjallajökull in Iceland, which forced the cancelation of thousands of flights, stranding millions of passengers.

Finally, the authors also address the possibility of future Laki-like volcano eruptions and the devastation they could bring. The British government already has an Icelandic volcano eruption on its list of high-risk events and has made preparations for such a disastrous event.

One of Saxo Bank’s "Outrageous Predictions" for 2015 was that an eruption of Bardarbunga would cloud the skies over Europe and call for a doubling of food prices. Although these predictions are for typically unlikely events that would have significant consequences for global markets should they come to pass, several previous predictions have come true.

Chapter One from “Island of Fire: The Extraordinary Story of a Forgotten Volcano That Changed the World:”

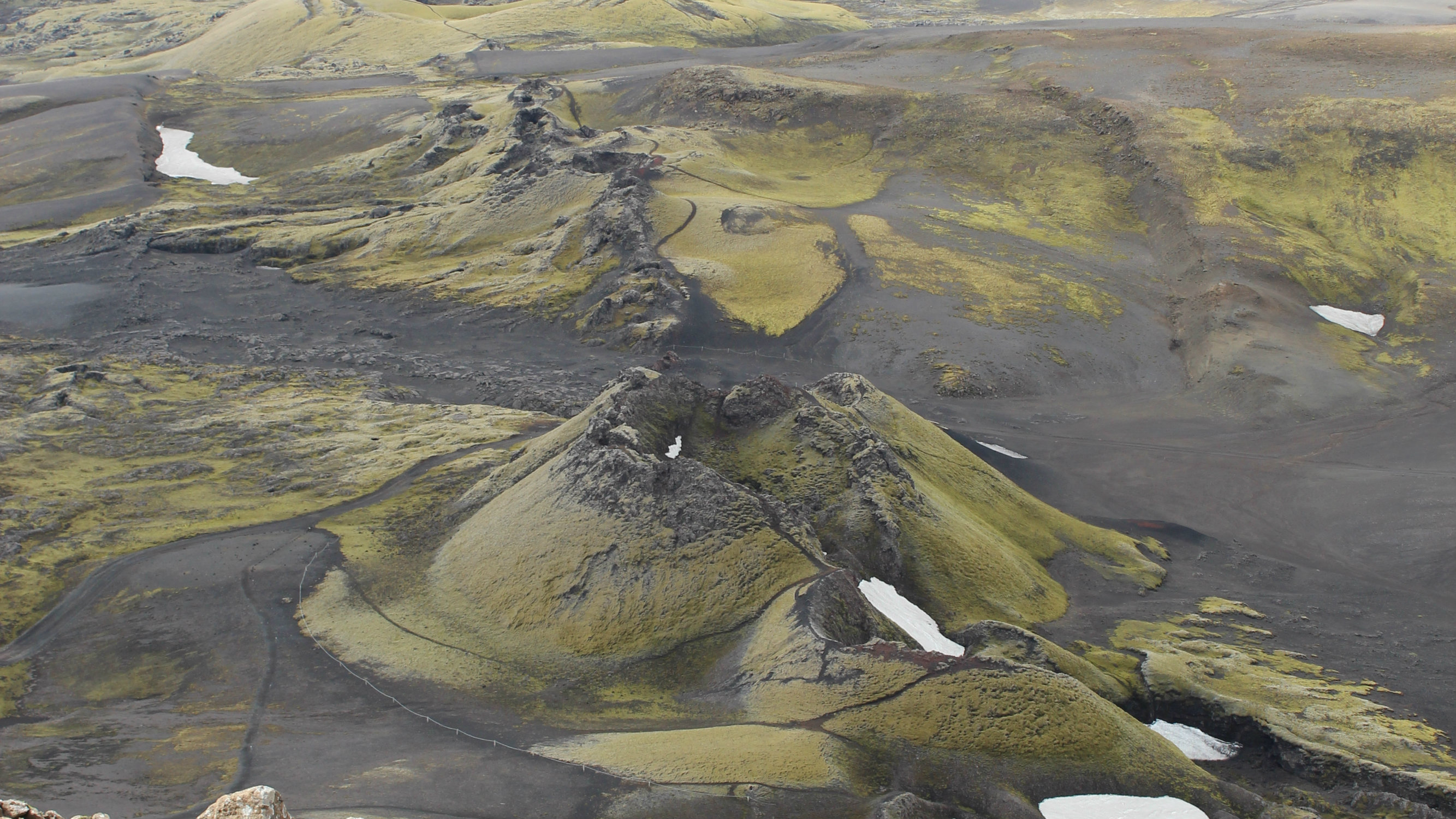

| Around 9 a.m. on Sunday, 8 June 1783, Reverend Jón Steingrímsson stepped out of his small farmhouse, mounted his horse and began the five-kilometre journey to church. Sunday services were always his favourite part of the week, but he was particularly looking forward to today’s observance. It was Pentecostal Sunday, also known as Whitsun, which commemorates the appearance of the Holy Spirit among the disciples of Christ after his resurrection. It was to be a day of celebration and reflection, and Jón was expecting his little Lutheran church to be brimming with worshippers. For the past five years, as priest of the Sída district in southern Iceland, the 55-year-old clergyman had overseen what he considered to be a happy and prosperous spiritual flock. Jón and his family too had prospered, so much so that his farm was nearly overrun with sheep and cattle. His affluence had allowed him to host expensive weddings for two of his daughters, including a substantial dowry for each. He was the very model of a successful rural preacher. Jón knew well how strenuous life in Iceland could be. But on this bright and clear Whitsun morning, with sunlight playing over the lush pastureland and the sheep and lambs grazing among the wildflowers, God seemed to be smiling. Then Jón chanced to look northward over his shoulder, and abruptly his reverie dissolved. He pulled up his horse and gazed in wonder and alarm. Looming over the foothills was an enormous, roiling black cloud. This, Jón thought, was the end. The earthquakes that had shaken the ground over the last few days, some strong enough to frighten people out of their homes, had been but a clamorous prelude to something he had grimly foreseen. God’s patience had run its course; the hour of afflictions had arrived. Whitsun would not be a day of celebration, but one of weeping and lamentation. Within minutes the cloud was so thick it shut out the sun and drove everyone indoors, where even lamplight could barely dispel the enfolding darkness. People caught outdoors had to grope their way home in the blackness. Soon, a blizzard of powdery fluff began falling out of the cloud, settling thickly on the ground like coal ash. A light drizzle followed, turning the flakes into an inky slurry. A brief respite came later in the afternoon, when a southeasterly sea breeze drove the ash cloud back across the foothills. Jón managed to conduct his services under a clear sky, but the relief was only momentary. That night the earthquakes returned. Then all hell broke loose. In the days that followed came more tremors, more ash and cinder falls, darkness, filthy air and bitter acidic rains that burned the eyes and skin and scorched the pastures. Thick haze rolled across the countryside, accompanied by a devilish stink. Pastoral Iceland, once full of lush grassy meadows, became a grey and poisonous place. At the time, neither Jón nor anyone else knew that the source of these earthly convulsions was the eruption of a new volcanic fissure system in the Icelandic highlands, some 45 kilometres to the northwest. Later the system would be given a name: Lakagígar, or the Laki craters, after Mount Laki that stands at the centre of the fiery seam. (Throughout this book, ‘Laki’ will be used as shorthand for both the Laki crater row and its 1783–84 eruption.) Laki erupted for eight months, and eventually, indirectly, it killed at least half of the country’s livestock and one-fifth of its people. Icelandic historians would come to consider the eruption the single most devastating event since Vikings settled the island in 871 C.E. The terrible irony was that the people in Jón’s district had just clawed their way back to relative prosperity. A decades-long string of disasters had begun in 1750 with bitterly cold temperatures. Sea ice congealed around the coasts, preventing farmers from open-boat fishing during the winter, a practice that normally sustained them through the off season. Livestock perished, villages were devastated and several thousand people starved to death. As if that weren’t enough, the volcano Katla erupted in the autumn of 1755, destroying much of the pastureland with ash fall and floodwaters. The weather improved slightly thereafter, but a smallpox outbreak ravaged the country in 1760, followed by scabies, which in eighteen years slashed the country’s precious sheep population by nearly half. Since then, however, the climate had moderated, the epidemics had diminished and Icelanders had enjoyed great bounties from the land. Good fishing had returned, the hay meadows were lush again and everyone had more than enough livestock for milk and meat. The country’s population, which had dwindled to 43,000 in the depths of the famine, now surpassed 50,000. But this surfeit, which Jón believed should have had people dropping to their knees in gratitude, seemed to make them more self-absorbed and uncharitable. Even as they prospered, he noted acidly, they became increasingly arrogant, lazy and debauched. Farmers had so many sheep that they gave up counting them. Food was so abundant that even servants turned up their noses at any but the richest victuals. The consumption of tobacco and alcohol increased: ‘During a single year here,’ Jón later wrote, ‘spirits amounting to the worth of 4,000 fish were consumed at feasts, visits and the like.’ Some clergymen showed up drunk to lead services. Their behaviour reminded Jón of a saying by his favourite Roman poet, Ovid: ‘More often than not men fall into excess when their affairs run smoothly.’ To Jón’s way of thinking, the impending disaster should have surprised no one. The supernatural portents were there for anyone to see. A fiery redness had appeared in the sky, and several years earlier ‘monsters of various shapes’ had been spotted in a stream to the south. ‘Fireballs lay in heaps like foxfire’ in a nearby coastal village, and ‘noxious flying insects’ moved across the land, he wrote in a chronicle describing the of the Earth, and ethereal bells rang through the air. More than the usual number of lambs and calves had been born deformed. In one case, Jón reported, a lamb on a nearby farm was born with the claws of a predatory bird instead of hooves. Elsewhere, horses were said to feed from dung heaps. Time and again Jón had warned his parishioners that such omens preceded misfortune. Just as God sent signs to people when they were awake, he also spoke to them when they slept, or so Jón believed. He put great stock in the predictive power of dreams, including his own. In the spring of 1783, many signalled that great changes were coming. In one of his dreams, Jón wrote, a man appeared in a house full of farmers who were making merry and singing over their drinking cups. When they offered the stranger a cup and asked him to sing a ‘merry ditty,’ he cried out in anguish: ‘The sun! The sun! The sun! Doomsday will soon be upon us!’ The farmers rebuked the stranger for being so gloomy. But in his dream, Jón told the farmers not to mock him. Jón then asked the stranger his name, and he answered that he was called Eldrídagrímur. (‘Eldur’ is Icelandic for ‘fire’.) Jón asked if he had visited the area before, and the man replied that he had, ‘in the year 1112’. Jón’s dream apparently ended there, but later, when he consulted a book of annals, he learned that in that year great lava flows had devastated the land (possibly a reference to the 1104 eruption of Hekla). In another dream, a ‘regal’ figure approached Jón and advised him to preach the thirtieth chapter of Isaiah. At the time, Jón was feeling guilty for having to cancel church services nine Sundays in a row because of bad weather. But the visitor told him that the following Sunday would have fair weather – which, apparently, is how it turned out. Just in time, it seems, for Jón to convey his message. Chapter 30 of Isaiah opens with God’s rebuke to the kingdoms of Jerusalem for believing that they no longer need him, and concludes with the Lord’s terrible judgment of the Assyrians: And the Lord shall cause his glorious voice to be heard, and shall show the lightning down of his arm, with the indignation of his anger, and with the flame of a devouring fire, with scattering, and tempest, and hailstones ... For Tophet is ordained of old; yea, for the king it is prepared; he hath made it deep and large: the pile thereof is fire and much wood; the breath of the Lord, like a stream of brimstone, doth kindle it. Jón’s interpretations of his environment and his dreams were not purely theological – he had an abiding interest in the natural world as well. After all, he had been born and raised in one of the most volcanically active countries on the planet. Like many Icelanders, Jón had witnessed eruptions and their effects, such as the great glacial floods that rushed down from the ice-buried Katla in 1755. Unlike many Icelanders, however, he also noted how ash from these historic eruptions was distributed around the country, so that in one place there might be five ash layers in the ground and in others eleven or more. He saw these layers as being a kind of historical record, relaying stories of the severity of earlier eruptions and, by inference, the human costs. Today this is standard volcanological wisdom, but in the backwoods of Iceland in 1783 it was cutting-edge. *** To be sure, it didn’t take an observer as keen as Jón to see that some sort of volcanic event was in the offing. In the spring of 1783, a bluish smoke had been observed drifting over the ground, though no one knew its source. In early May, the crew of a Danish brig sailing around Iceland’s southern coast claimed to have seen columns of fire shooting in the sky in the mountains north of Jón’s district. Some weeks later, the Skaftá River rose to uncommonly high levels, breaching its banks violently in places, and the water was muddy and foul-smelling rather than clear and fresh. And then there were the violent earthquakes in the days leading up to Whitsun. To Jón, the impending cataclysm would be known as the ‘Fires,’ the ‘Scourge,’ or even ‘God’s chastisement’. Within Iceland the eruption also goes by the name Skaftáreldar (‘Skaftár fires’), because the main flow of lava more or less followed the gorge of the Skaftá River to the southern coast. Modern geologists refer to the disaster as Lakagígar (if they are Icelandic) or Laki (if they are not), and consider it to be one of the most significant eruptions of the modern era. It changed both the history of Europe and the history of science. Yet most people outside of Iceland have never heard of it. Why does Laki remain so obscure? One explanation is that it does not fit the modern concept of what a volcano should be: unlike Italy’s Mount Vesuvius or Japan’s Mount Fuji, it does not tower scenically above a well-populated town. Laki is, instead, a series of low cones in barren ground tucked out of sight from the sparse farm settlements of Iceland’s southern coast. It is off the beaten track even for tourists making the rounds of the country’s popular ring road. Laki also falls short by other criteria. On the volcanic explosivity index – the standard 8-point scale scientists use to measure an eruption’s power – Laki rates a modest 4, one notch below the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens in Washington. Laki did not erupt with the apocalyptic bombast of Indonesia’s Krakatau, whose explosion in 1883 sent shock waves racing around the globe seven times, or Mount Pelée on the Caribbean island of Martinique, which in 1902 obliterated an entire town of 30,000 people within minutes. Laki did generate floods and fast-moving lava flows, but these generally followed the course of rivers and gorges and did not invade villages or settlements. But Laki should not be underestimated because it didn’t annihilate thousands of people outright. What made Laki particularly deadly – an insidious killer – was how long its eruption went on and what poisons it spat into the atmosphere. Over the course of eight months Laki produced one of the largest lava flows in historic times, enough to bury Manhattan 250 metres deep. Over the first twelve days it disgorged the equivalent of two Olympic swimming pools full of lava every second. Along with the lava came the gas: Laki belched out an estimated 122 million tonnes of sulphur dioxide, 15 million tonnes of fluorine, and 7 million tonnes of chlorine. It was one of the biggest atmospheric pollution events in the past 250 years. Laki heaved and spewed particles that spread eastward across the North Atlantic and descended on Europe. All summer, people all over the continent choked on this caustic smog. As we will see in chapter 5, people could neither avoid nor escape the malignant haze, which manifested itself as a bluish or reddish ‘dry fog’ that smelled strongly of sulphur. It dimmed the sun and instilled panic across the continent. Londoners were used to pollution, but this volcanic fog was interminable and highly toxic. Those prone to respiratory or heart ailments were particularly vulnerable. Tens of thousands of people in England and France died of causes that were inexplicable to doctors and scientists at the time. The vast cloud of Laki’s sulphur emissions proceeded to encircle the northern part of the globe, reflecting sunlight back into space and cooling the planet by a degree Celsius for several years. The cooling trend wreaked havoc with the weather. In Europe and North America the winter of 1783–84 was one of the worst in 250 years. Crops perished, setting up long-lasting hunger and social unrest that some scholars have linked to the French revolution of 1789. Further afield, harvests failed in Egypt, India and Japan, leading to famines that killed millions. Back in Iceland, perhaps the most lethal aspect of the eruption was how it poisoned the countryside. Laki was unusual in that it had tapped an underground magma chamber that was rich in fluorine. In low doses in humans, this element can have beneficial effects, such as the hardening of tooth enamel and the stabilizing of bone mineral. High doses, however, result in fluoride poisoning. For more than 7,000 square kilometres around Laki, the ground was heavily salted with fluorine. Animals grazing in polluted pastures ingested ash that corroded their intestines, leading to fatal haemorrhages. Others developed severe bone and teeth deformations. Death, when it finally came, would have been merciful. With no sheep for meat or cattle for milk, and no fish to gather from poisoned rivers, the livelihoods of whole communities collapsed. Famine set in, slowly but steadily. Farmers who had worked the same land for generations abandoned their homes in a futile effort to get away from the killer volcano. Beggars and vagrants moved in. At least one man kicked out his wife for feeding too many of the hungry people who arrived at their farm’s door; generations later, her descendant Haraldur Sigurdsson would become one of Iceland’s most famous volcanologists. Rumours flew that officials in Copenhagen, from where the Danish king ruled Iceland, were planning to evacuate large swaths of the stricken country. No wonder, then, that Laki is burned into Iceland’s national psyche and taught in every history class. The eruption and its aftermath have become a benchmark for measuring all other painful episodes in that country. Icelanders have a word for it – Móduhardindin – meaning ‘the hardship of the fog’. Laki was the most severe disaster to happen in Iceland for centuries, not just for the number of lives lost but also for its long-term effect on the development of the entire country. It helped keep Iceland as the remote place it had been for so long. *** Although the Laki eruption would test Jón’s faith and mettle almost beyond bearing, probably no one in Iceland was better prepared than he to cope with or understand the imminent catastrophe. By all accounts, he was a man of extraordinary aptitude and insight. He kept a near-daily chronicle of the months that followed 8 June 1783. This diary, known as the Eldrit or ‘Fire Treatise’, would not only document the terrible consequences that Laki would have for Icelanders, but also inspire future research into this exceptional eruption. Jón was born in 1728, the eldest child of a farming family near the village of Hólar in northern Iceland. It’s hard to overemphasize how simple rural life was at the time. Daily life focused on the health of a family’s sheep, as one harsh winter or a livestock epidemic could reduce the strongest farmer to ruin. Social life revolved around the village; the king in faroff Denmark, which had ruled Iceland since 1660, was only a vague concept. Local officials appointed by Copenhagen oversaw such matters as markets and law courts, but otherwise the farmers handled most affairs among themselves, referring to the local preacher for guidance on occasion. Like most such farmers, Jón’s parents were pious and humble. His father taught him to bare his head and recite the Lord’s Prayer and other words of blessing before tending the sheep, so that ‘nothing evil would befall him’. During the day, he would regularly recite or hum hymns to himself. He even used one of his father’s favourite hymns, ‘One Lord I Prize Above All’, to gauge distances. The hymn had ten verses, and it took him forty repetitions to get from home to the sheep pen. By the age of nine, Jón had developed a keen interest and skill in working pasturage, a vocation he might have pursued had his father not taken ill and died the following year. His childhood came to a halt, and the family descended into near-poverty. Jón’s mother, a widow with five mouths to feed, hired an overseer to supervise the labourers and manage the property. Somehow, the family managed to scrape by. Young Jón hoped to rise out of impoverishment by attending the diocesan school in Hólar, which was intended mainly for the training of future priests. But his family could not afford it, and he spoke with a stammer that did not impress the teachers there. Eventually, with his mother’s encouragement and support from others, Jón obtained a scholarship and proved to be an excellent student. He graduated in 1750 with a solid foundation in Latin and classical literature. By this time, aged twenty-two, Jón had also developed certain characteristics that today we might regard as eccentric. As we have seen, along with his profound faith and an interest in nature he believed in portents and dreams as revelations of future events and God’s will. He considered himself sensitive to ghosts, and in his autobiography he recounts several stories of encounters with evil spirits, including one in which a poltergeist lifted him bodily in the air and threw him across the room. Jón was not alone in his supernatural worldview, however. Many Icelanders believed (and still do, to some extent) in the existence of spirits, monsters and ‘hidden people’ or huldufólk (elves and trolls). Mystical drawings and incantations, it was thought, could harness supernatural powers for good or ill, and some individuals were held to be clairvoyant. Such convictions, along with strong religious beliefs, lent order to a world that was rife with inexplicable forces. After Jón graduated, many of his friends and relatives assumed that he would sail to Denmark to continue studies at the University of Copenhagen, as most young promising Icelanders did. But providence had other plans. At a farm near Hólar lived a wealthy farmer named Jón Vigfússon and his wife, Thórunn. Vigfússon, a former soldier, often went on drinking binges for days at a time, during which he might wave his sabre at anyone who crossed him. More often than not he turned his aggression on his wife, beating and choking her. If any man tried to stop him, Vigfússon would accuse him of sleeping with Thórunn. Concerned, the bishop of Hólar offered to appoint Jón as deacon of the church that stood on Vigfússon’s property, partly in the hope that his calming presence might quell the man’s violence. Jón accepted the post, leaving dreams of Copenhagen behind. For a while, Vigfússon’s drinking and brutality continued unabated – the situation was so bad that on one particularly grim day, Jón and some members of the household agreed that ‘it would be better if the master were dead’. Astonishingly, not long after, the master was found dead in his bed, apparently from liver or heart failure. Vigfússon’s decease was Jón’s relief, because he was secretly in love with the abused wife. Thórunn was not a natural beauty. Life had been hard for her: in twelve years of arduous marriage she had borne five children, two of whom had died in infancy. As Jón wrote later, she was ‘hollow-backed’ with a ‘protruding stomach’ and ‘a recessed hairline’. Smallpox had disfigured her face. ‘She had a very striking and attractive appearance when seen from behind,’ Jón wrote, seemingly without irony, ‘and gave an impression of utter goodness – a family trait – when one saw her from the front. Once Vigfússon was gone, Thórunn and Jón moved in together. Nearly a year to the day after his death, they were married. A very inconvenient few months later, however, their first daughter was born. The church took note, and Jón was removed from his post. Thórunn, who was fairly well off, owned property in southern Iceland, and in 1755 the couple decided to make a fresh start and move their family there. In September of that year, just before Katla erupted, Jón set out across central Iceland with his brother and a hired man to prepare for the move. The volcano turned out to be the least of their concerns. During the months-long journey, they nearly died in blizzards and bitterly cold temperatures. Their perseverance finally paid off, and by the beginning of winter they had made it to the south, settling on a farm by the sea, near present-day Vík. The farmer said they could live in a storehouse on the property, which was little more than a cave hewn into rock. Nevertheless, the brothers lived there happily during the winter, and the family joined them in the following spring. Over the next several years, Jón became a prosperous farmer and fisherman. This won him much admiration among his new neighbours, who often sought his counsel. He also caught the eye of the local priest, who, in failing health and unable to serve the entire district, invited Jón to become his assistant. Jón resisted at first because he and Thórunn were comfortable with their newly restored lives at the farm. More importantly, he was reluctant to serve under an ‘inflammable priest’ whom he thought had lax morals and was a heavy drinker. The priest, however, slyly solicited the help of Jón’s friends to convince him to take the position. Not wishing to offend them, he relented. In the final agreement, it was decided that the priest and Jón would oversee separate parishes in the district. Jón was apparently popular as an assistant priest for, a year later, most of the farmers in the parish sent him letters asking him to be their permanent clergyman. Wishing to separate himself entirely from the inflammable priest, Jón sent these letters to the bishop, who agreed to the arrangement. Accordingly, in 1760, Jón was ordained to the priesthood and moved to Fell farm, the local rectory. Priests at the time were expected to be farmers, and Jón’s boyhood training served him in good stead in that respect. He also developed another skill that garnered even more admiration from his parishioners: medicine. Being the autodidact that he was, Jón had studied the medical arts on his own and began practicing at Fell. He also trained for a while with a physician, natural scientist and former schoolmate named Bjarni Pálsson, who went on to become Iceland’s first surgeon general. Jón treated many people for free and was seldom without a resident patient in his home, sometimes accommodating two or three at a time. He later estimated that he successfully treated up to 2,000 people during his seventeen years of active practice. In 1778, the position of priest for the Sída district, to the east, fell vacant. Jón applied for and won the appointment. Now fifty years old, he had enjoyed being a priest in Fell, but he was ready to move on. The most painful experience was a lawsuit brought against him and Thórunn by Jón Scheving, the son of Thórunn and her detested late husband. Scheving had squandered his inheritance and was living a deadbeat lifestyle in Copenhagen. For some time, he had apparently harboured an intense hatred for his stepfather and mother, and he devised a plan to ruin them and appropriate their money. He bribed a hired hand to claim that his mother and Jón Steingrímsson had conspired to have his father murdered so that they could live together unimpeded. News of this scandalous accusation spread rapidly through Copenhagen and across to Iceland. Jón’s utterance that ‘it would be better if the master were dead’ came back to haunt him, because many people believed the stepson’s story. The lawsuit unravelled, however, when the hired hand retracted his testimony under investigative pressure and admitted that Scheving had paid him to make the charge. Upon learning that his scheme had been thwarted, Scheving signed up with a regiment of soldiers and transferred out of Copenhagen. Jón never heard from him again. Although Jón and Thórunn were exonerated, the experience continued to weigh heavily upon them, and when the position became available in the Sída district they jumped at the chance of moving. The job was in the town of Kirkjubæjarklaustur, commonly known as Klaustur, a tranquil place with a rich religious history. Well before the Vikings arrived to settle Iceland permanently, Irish monks occasionally visited the broad, richly forested slopes beneath the steep cliffs of volcanic rock. By the twelfth century nuns had established a famous convent here (the ‘kirk’ in the town’s name), and many of the natural features in and around Klaustur are still named for the sisters. It was a place Jón could feel comfortable in and thrive, and he would serve it for the rest of his life. Klaustur, it turned out, would also be an ideal location for witnessing the end of the world. *** In the days following the first appearance of the black cloud, Jón recorded new and more inauspicious manifestations coming from the direction of Mount Laki. On 9 June, the day after Whitsun, the weather started out clear and sunny, but ominously the dark cloud returned and was rising ever higher in the north. Earthquakes were drumming faster and faster, accompanied by thuds and loud cracking sounds. The Skaftá River, which normally flowed at a volume so great that horses at the ferry crossing had to swim some 120 metres through the current to ford it, suddenly began to drop. An acid rain fell the next day, eating through pigweed leaves and scorching the hides of newly shorn sheep. By the afternoon, the Skaftá had dried up completely. Snow fell from the black cloud on 11 June, creating a hard, shellac-like surface over the grass. The sun, when it could be seen, was red as an ember, and the moon blood-coloured. Then, on 12 June, lava gushed forth ‘with frightening speed’ from the Skaftá canyon southwest of Klaustur. As it encountered wetlands and other streams feeding into the river, the combination of water and molten rock created concussive explosions. At first, the lava followed along the course of the riverbed, but soon it breached the banks and began spreading over old lava flows, meadows and farmlands. This was to be the first of five such surges of lava from the gorge. Cinders fell from the sky on the 14th. They were, Jón wrote, ‘blue-black and shiny, as long and thick around as a seal’s hair’. This was the first description of what volcanologists today refer to as Pele’s hair – thin strands of volcanic glass formed by molten particles ejected in a lava fountain and stretched into fibres as they are carried through the air. Just half a millimetre across, they may be as long as two metres. The unusual fallout covered the ground across the region, and the winds worked some of the hairs into long hollow coils. The following day, a party of farmers decided to climb Mount Kaldbakur, eight kilometres northeast of Klaustur, to see if they could get a good view of the eruption site. They reported seeing lava coursing through the river gorge, and, off in the distance, twenty fountains of fire exploding high into the sky. The news terrified everyone, including Jón, for it seemed certain now that the lava would breach the mountains and ravage the settlements. Throughout the waning days of June, the forefront of the lava flow turned southeast, engulfing meadows and woodlands and laying waste to farms and churches. Birds fell dead from the sky and fish floated lifeless to the surface of streams and ponds. Earthquakes convulsed the ground and acrid odours filled the air, along with smoke and ash so thick that no one dared inhale deeply. The water tasted of sulphur and freshwater pools were fouled with ash. Thunderous eruptions could be heard coming from the glaciers up in the mountains. At night great showers of sparks shot into the sky. Lightning produced in the ash clouds was violent and at times continuous, so that ‘scarcely a moment passed between bolts for days on end.’ By early July, new lava was seen flowing under older lava, creating convulsions of subterranean fire and steam that caused the earth to heave upward and crack open. Some people desperately tried to relocate their livestock, but their efforts usually came to naught. The proprietor of one of the region’s most prosperous farms collected ‘a great number’ of his sheep and placed them on a small island in a river, intending to herd them to safety as soon as he had an opportunity. Before he had returned to his house, however, the lava came rushing on more quickly than he expected. It rapidly engulfed the island and consumed the sheep. Many owners abandoned their homes and land, vowing never to return. Others made preparations to leave and then decided to wait and see if the lava flow would reach the sea, in which case they and their families would flee eastward. ‘All the schemes, projects, and remedies that people undertook,’ Jón wrote, ‘led to confusion, frustration, exhaustion and expense, and in most cases were totally unavailing.’ Between July 13th and 19th, the lava edged further down the Skaftá riverbed toward the east, making its way – seemingly inexorably – toward Klaustur and Jón’s church. In some places the lava piled up so high that it blocked the noonday sun. In other places floodwaters inundated farmlands, reducing them to muddy sloughs. For more than a week, suffocating clouds of smoke blanketed the area, forcing people into their homes. Because of the encroaching lava, the estate overseer at Klaustur decided to remove as many valuables and ornaments from the church and cloister as possible. For Jón, relocating church accessories such as the altar, chalice, paten and other sacred vessels must have been a sorrowful turning point. By 17 July, residents fleeing the lava’s advance west of Klaustur were streaming into the area, herding their cows before them. (Most of the terrorized sheep had fled in all directions.) Two nights later, the tumult subsided somewhat, though the relative calm was occasionally broken by thunder and distant cracking sounds. The approaching lava now lay less than three kilometres from the church. In his home nearby, Jón lay in sleepless dread, praying and fretting over a terrible, dawning truth: that tomorrow would most likely be the last day he would ever hold service in his beloved chapel. Its destruction seemed certain. Reprinted from Island on Fire: The Extraordinary Story of a Forgotten Volcano That Changed the World by Alexandra Witze and Jeff Kanipe with the permission of Pegasus Books. Copyright Alexandra Witze and Jeff Kanipe 2015 |