For a several weeks, students at Sheridan Middle School prepared for the school’s first debate and the topic was gun control.

For a several weeks, students at Sheridan Middle School prepared for the school’s first debate and the topic was gun control.

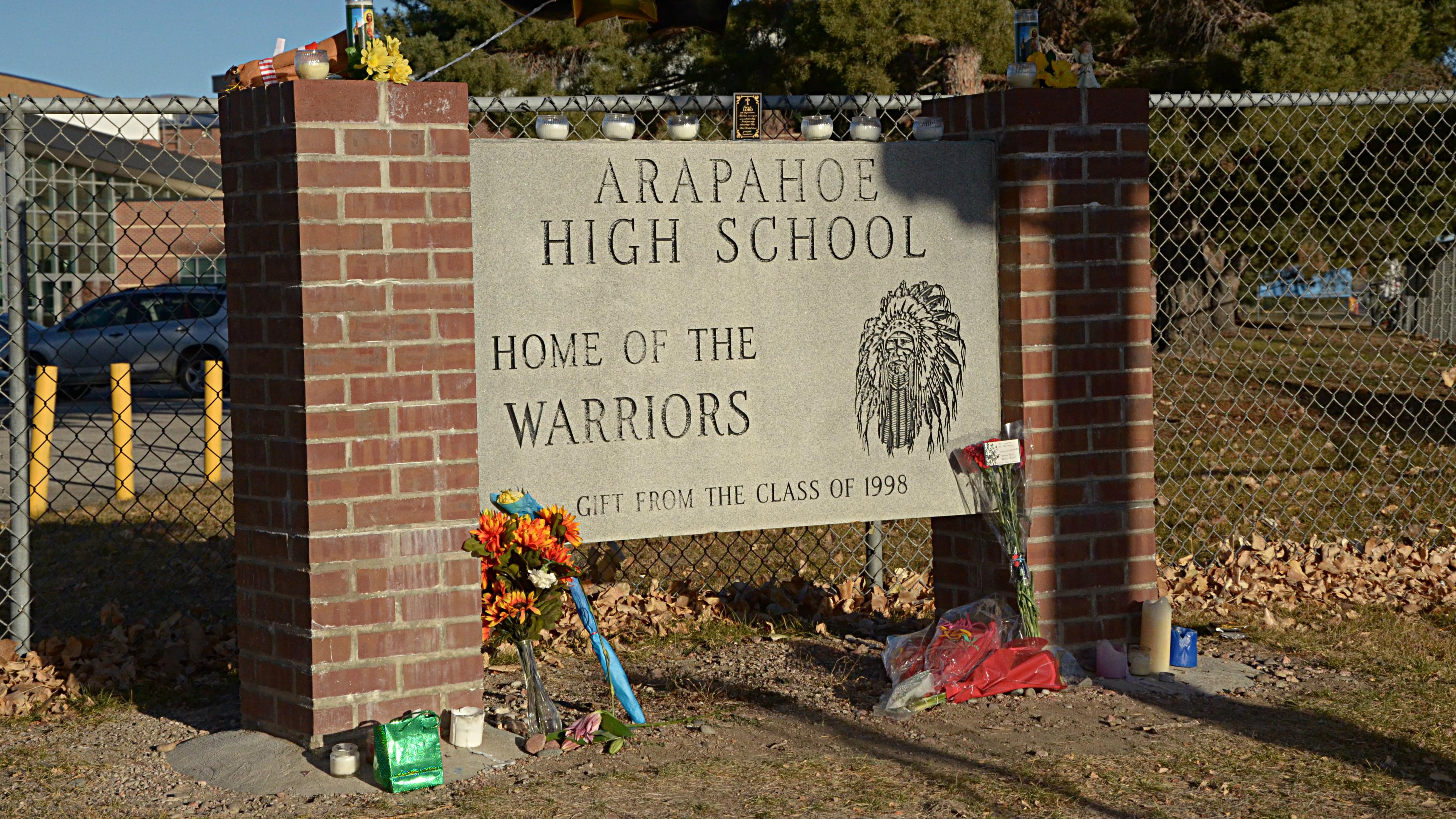

With less than a week to go, during focused efforts to prepare for the debate, a student gunman opened fire at nearby Arapahoe High School, critically wounding one student.

The tragic shooting gave sobering, new meaning to the debate set to take place at Sheridan and, after some reflection, the Sheridan students decided to carry through with the debate as scheduled on Tuesday.

There have been at least 285 school shootings nationwide since Columbine in 1999, including the Arapahoe High shooting, according to data from the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence.

Ryan Warner talked with CPR Education Reporter Jenny Brundin, who attended the debate, about what the students thought about school safety. The following Q&A captures their discussion:

Ryan Warner: Jenny, tell us about the debate these students were engaged in.

Jenny Brundin: The question -- should the federal government make stricter gun laws? The first student speaking began by asking audience members who had a loved one injured or killed by a firearm. I was struck by the fact that almost everyone in the room raised a hand.

Ryan Warner: So what kinds of arguments did the students make?

Jenny Brundin: Most of them were the traditional arguments you hear in the gun debate, such as people should have the right to hunt or questioning whether a “well-regulated militia” means citizens with assault rifles. The students followed parliamentary procedure. There was pounding on the tables to applaud or show support for a teammate.

Ryan Warner: The students sound really passionate. Afterwards you spoke to some of them about school safety. What did they tell you?

Jenny Brundin: Listening to them was sobering and I must say slightly heartbreaking as I looked into their faces. This is their reality now. This is the world they live in. Though kids may say to their parents they’re OK and they don’t really think about the shooting, these kids say, it is something that worries them, especially because Arapahoe High isn’t far from their school. Students Joshua Benavides and Crystal Baca said kids can’t help but think what if it happened at their school.

Joshua Benavides: It just gets you going, wondering what will happen during that time. You’re like thinking about your family members and you want them to be safe also. ‘You’re saying, we should be safer and more caring to one another.

Crystal Baca: Because we think what about if we were in that situation because we think about our friends and our family and everyone that could have been in that shooting. So I think it sticks in our brains knowing you could die in your school.

Ryan Warner: “Knowing that you could die in your school.” So this really is something parents can’t relate to on a personal level as they didn’t experience it when they were young. But do these kids feel safe in their school?

Jenny Brundin: Yes, they do, although the Arapahoe shooting has left them a little unsettled. The school has a lot of safety measures in place, like a lot of schools. There’s a security officer and a locked front door and kids continually referred to their teachers as people who could protect them. Here’s Karen Lopez and Yarely Romero:

Karen Lopez: Sometimes I do feel safe, but when tragic events happen like the Arapahoe shooting, I feel like it could happen to our school at any time.

Yarely Romero: Sometimes I feel safe and sometimes I don’t because when shootings happen in schools, it makes you think you’re kind of safe with the teachers around you but at the same time you’re not because you never know if that teacher knows how to protect themselves or you and if that shooting happens then you’re gone or someone else is gone and you lose another life.

Ryan Warner: Since Sandy Hook, schools have refined what are called “lockdowns.” They practice them a few times a year.

Jenny Brundin: Yes. Along with trying to understand algebra, kids must also prepare for bad people who may open fire in their classrooms. Lockdowns have become a normal part of school. They can occur, for example, if the police department calls to say a criminal is loose in the neighborhood. For people not familiar with a lockdown, here’s how Crystal Baca describes it:

Crystal Baca: During lockdowns we all go into a protective area. We make sure [we’re not by] windows or no one can see us. If a shooter came in or something then our teachers would be able to protect us or they wouldn’t be able to find us.

Jenny Brundin: I asked them if they think lockdowns are a good idea. Most said “yes.” Here’s Crystal again followed by Yarely, who has a different view:

Crystal Baca: I think it is a good idea that kids practice it because you never know when it could happen and it’s always nice to know what to do if it does happen.

Yarely Romero: Some students don’t take it seriously. They start talking and making a lot of noise. And you’re supposed to feel safe during a lockdown, making sure no one can see you and having students talking and making funny noises and all that stuff, the shooter can find you and shoot us.

Jenny Brundin: And here, the principal interjected to explain that in Yarely’s lockdown drill, there had been a substitute teacher. Afterwards the principal went into that classroom and talked about safety and laid down the law on not goofing around during lockdowns.

Ryan Warner: After some of the school shootings, there’s been renewed debate about violent video games and how they affect the teenage mind.

Jenny Brundin: Even some gamers are becoming concerned about new games “fetishizing” and marketing violence. The Sandy Hook shooter was reportedly obsessed with the weaponry in the game ‘Call of Duty.’ Sony's 'The Last of Us' ends with a villain taking a gunshot to the face.

Ryan Warner: So we’re not saying video games “cause” violence here – there are plenty of studies looking into that – but what did the middle schoolers have to say about video games themselves?

Jenny Brundin: They had a range of views, with some of them sensing that ‘Hmm, it may not be the best thing for very young minds to have a steady diet of this stuff.' Others didn’t see a problem. Here’s Joshua and Crystal:

Joshua Benavides: It truly does have an impact on kids. When they get older, they recognize ‘Oh, I should not do that.’ They get awareness. I think it does have an impact on kids if they play violent video games and first-person shooters or something like that, they have a mental thought, ‘Oh, I can do whatever I want.”

Crystal Baca: I don’t think video games, well they could influence them. But overall, they know that a video game is just a video game. They know that if they try to do that in real life, they could get injured or get in trouble.

Ryan Warner: So people are grappling with the question: What should be done next? It’s a complex puzzle; you’ve guns, mental health, school security, counseling, preventative measures. What did these kids say?

Jenny Brundin: One girl recommended stricter school security and better background checks for gun purchases. She suggested guns being locked in boxes with codes that only the owners know. Many believe that mental illness and anger are what is pushing kids towards violence and that people need to take the time to care for one another. Here are some of the other views. We’ll hear from Yarely, Eliza Ruiz and Karen Lopez:

Yarely Romero: I know that teachers are not allowed to have guns in schools but at least they should know how to defend themselves, like self-defense. At least be able to have something to protect us and them and also some schools have their front doors open. They should at least lock all those doors to make sure no one would be able to get in or the windows should be at least bullet-proof so no one would get injured in that situation.

Eliza Ruiz: I think the schools should make the children practice lockdowns and fire drills occasionally so then that they’ll be prepared when a situation like a shooting occurs.

Karen Lopez: I think that kids should be more open about their feelings because a lot of shootings occurred because kids felt alone or sad or mad. So I think if kids were more open or if adults asked kids about their feelings more, then things like this wouldn’t occur as often.