This interview first aired May 10, 2016

Theodore Roosevelt missed out on fighting in the Civil War because he was still a young boy when it ended. But he idolized the heroes of that war. That was one reason he lobbied, as assistant secretary of the Navy, for the U.S. to do battle in Cuba, in what became known as the Spanish-American War.

With instructions from Congress, Roosevelt helped form a band of volunteer fighters known as "The Rough Riders." The idea was to recruit the stereotypical "cowboy" of the American West, who was thought of as "a natural-born, crack-shot fighting man by a public fed on shoot-'em-up dime novels and thrilling performances from Buffalo Bill's Congress of Rough Riders of the World," according to a new book by Mark Lee Gardner. In reality, Gardner discovered that the Rough Riders unit included a number of Ivy League-educated, high-society men from the northeast who were friends with Roosevelt.

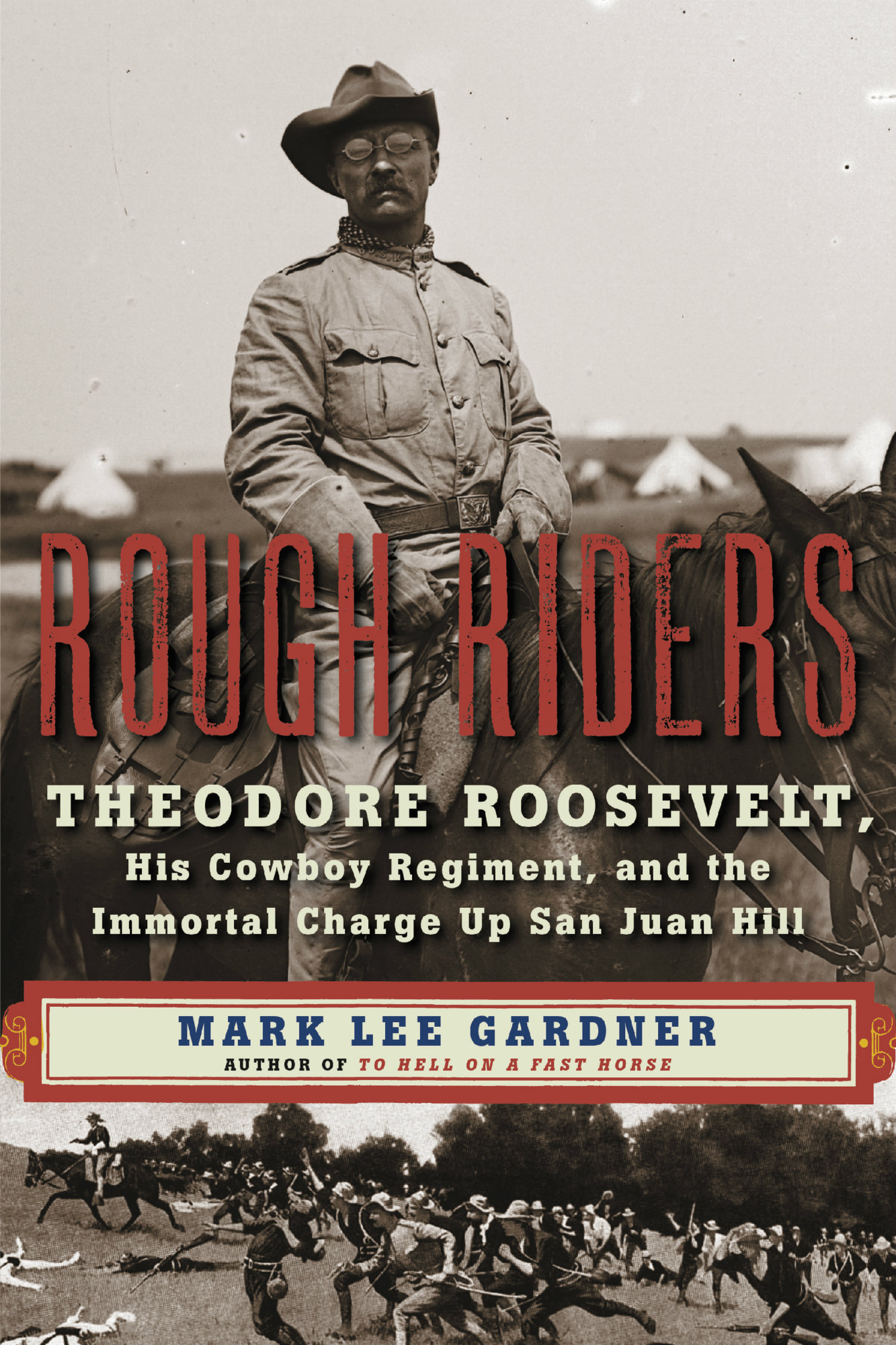

"Rough Riders: Theodore Roosevelt, His Cowboy Regiment, and the Immortal Charge Up San Juan Hill" comes out today. Gardner is an author and historian from Cascade, Colo. He spoke with Colorado Matters host Ryan Warner.

- "The Big Burn" Teddy Roosevelt & The Fire That Saved America"

- Interactive Map: Battle Of San Juan Heights

Read an excerpt:

CHAPTER ONE I think I smell war in the air. - Frederic Remington Frank Brito rode through the darkness, his cow pony’s shod hooves making a slow, steady clopping on the hard dirt. Occasionally there would be a sudden scraping sound when its hooves struck a rocky outcropping, or a jolt to the rider when the pony stepped into a small ditch or arroyo. Brito was riding through the rough country between Silver City, New Mexico Territory, and the mining town of Pinos Altos (“tall pines”), where his parents lived. It was now nearly midnight, and he was dog tired: he had been in the saddle for hours. But he was almost home, just a few more miles. The twenty-one-year-old Brito had been born at Pinos Altos. His parents, natives of Mexico, were of Yaqui Indian heritage. His father, Santiago, had worked various gold claims at Pinos Altos since long before Frank’s birth. As a young man, Frank had set type in the small office of the weekly Pinos Altos Miner, and he had grown up to be a handsome fellow, standing five feet eight inches tall with a dark complexion like his parents, coal black hair, and striking blue eyes. That spring of 1898, Frank had been pulling in a dollar a day as a cowpuncher for southwestern New Mexico’s Circle Bar outfit. But he had received a message from his father to come back to Pinos Altos immediately. His father knew Frank was a ten-hour horseback ride from home, so Frank knew he wouldn’t have sent for him unless it was something important. Finally, as Frank’s pony neared the old place, he could see that the house was all lit up, oil lamps glowing in every room. Frank’s first thought was not a good one: surely someone must have died. Santiago Brito had been waiting anxiously for his son. When he heard Frank’s pony approach the house, he came out onto the porch. Before Frank could slide out of the saddle, Santiago told him that the United States had declared war against Spain. He had gotten the news from nearby Fort Bayard, so there was no doubt about it. More important, Santiago had learned that the government had authorized a volunteer regiment to be composed of cowboys and crack shots from the western territories. Santiago told his son that first thing in the morning, he and his older brother, Joe, were going to ride to Silver City and enlist. “In those days,” Frank would recall decades later, “you didn’t talk back to your father, so we did it.” This war with Spain was no surprise to Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt. For months, he had been doing everything in his power—not always with the direct knowledge or approval of the secretary—to make the navy ready for the great conflict he was certain was coming. And he also let it be known that he had no intention of observing the war from afar. Crazy as it sounded—and more than a few did think Roosevelt was crazy—this lightning-rod bureaucrat intended to go where the bullets were flying. He had been waiting for a war, any war, his entire adult life, and now that it was here, nothing was going to keep him from the battlefield. Many would blame Roosevelt’s outsized martial spirit on the family’s supposed stain of his father not taking up arms in the Civil War. Theodore Senior was a staunch Lincoln Republican married to a staunch southern patriot from Georgia, and rather than deepen the divide within his family by becoming a Yankee soldier, he had paid a substitute to serve in his place (an option many well-off men in the North took advantage of ). Theodore Junior would later write, “I had always felt that if there were a serious war I wished to be in a position to explain to my children why I did take part in it, and not why I did not take part in it.” But Roosevelt’s war fever was actually due to America’s fever for war, or at least its long glorification of all things military. The Civil War had erupted just three years after Roosevelt’s birth in a New York City brownstone, and that terrible conflict had exerted a strong influence on a most impressionable boy. Two of his uncles on his mother’s side served in the Confederate navy, and little Theodore witnessed his mother, aunt, and grandmother pack small boxes of necessities destined for the wrong side of federal lines (surreptitiously, of course, while Theodore Senior was away). Nearly everything about the Civil War seemed glorious to a boy far removed from the actual fighting. The best and most popular songs of the day were martial songs, from the rousing “The Battle Cry of Freedom” and the poignant “Just Before the Battle, Mother” to the tragic “The Vacant Chair.” The oversized pages of Harper’s Weekly and Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper were chock-full of spectacularly detailed engravings of saber-wielding cavalrymen at full gallop, smoke-belching cannons, and corpse-strewn battlefields. And there were the dignified portraits of the war’s many heroes, both North and South: Grant, Sherman, Sheridan, Lee, Jackson, Stuart, and the like. After the Civil War, veterans were showered with adulation for the rest of their lives. The erecting of commemorative monuments and markers on numerous battlefields became a minor industry. And there were the Fourth of July parades, the reunions, and, for many, high political office. In the United States, the quickest way to fame and votes at election time had always been the winning of laurels on the battlefield. No wonder young men born too late for the great Civil War hoped they would be given their own chance to prove themselves, in their own war, on their own fields of valor. Theodore Roosevelt clearly was one of these. In 1882, as if his job as New York State’s youngest assemblyman wasn’t enough of a responsibility, he joined the New York National Guard, eventually rising to the rank of captain. But the Guard mostly set up camps and drilled, which was a lot like playing soldier. No enemy. No thrill of battle. No glory. Then, in the summer of 1886, Roosevelt sniffed an opportunity to get into a real fight. At the time, he was cattle ranching in the Badlands of Dakota Territory. Roosevelt was one of a number of well-to- do young easterners who were drawn to the Wild West for its business opportunities—and adventure. As a passionate hunter, the Little Missouri River country was appealing to him with its last small herds of buffalo, as well as deer, elk, and even bighorn sheep. “It was a land of vast silent spaces,” he wrote, “of lonely rivers, and of plains where the wild game stared at the passing horseman.” And it was an escape. Roosevelt had lost his first wife, Alice, and his mother on the same cold February day in 1884, his wife to Bright’s disease after giving birth to their daughter, his mother to typhoid fever. Roosevelt had met and fallen in love with Alice while a student at Harvard; they had been married less than three years. The page in Roosevelt’s diary for February 14, the date of those two tragic losses, contains only a black “X” and the words, “The light has gone out of my life.” For Roosevelt, the long days on a working cattle ranch and his numerous hunting excursions helped him push away the sadness and reinvigorate himself. But during his brief career as a rancher, Roosevelt never completely cut his ties to the East or its politics, and his blood rose when he read the newspaper reports of growing tension between the United States and Mexico over the false imprisonment of an American newspaper editor in El Paso del Norte, Mexico. The United States was demanding his release, and Mexico was refusing. Texans called for war, and rumors swirled of troops mobilizing on both sides of the border. From ROUGH RIDERS by Mark Lee Gardner. Copyright © 2016 by Mark Lee Gardner. Reprinted by permission of William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. |