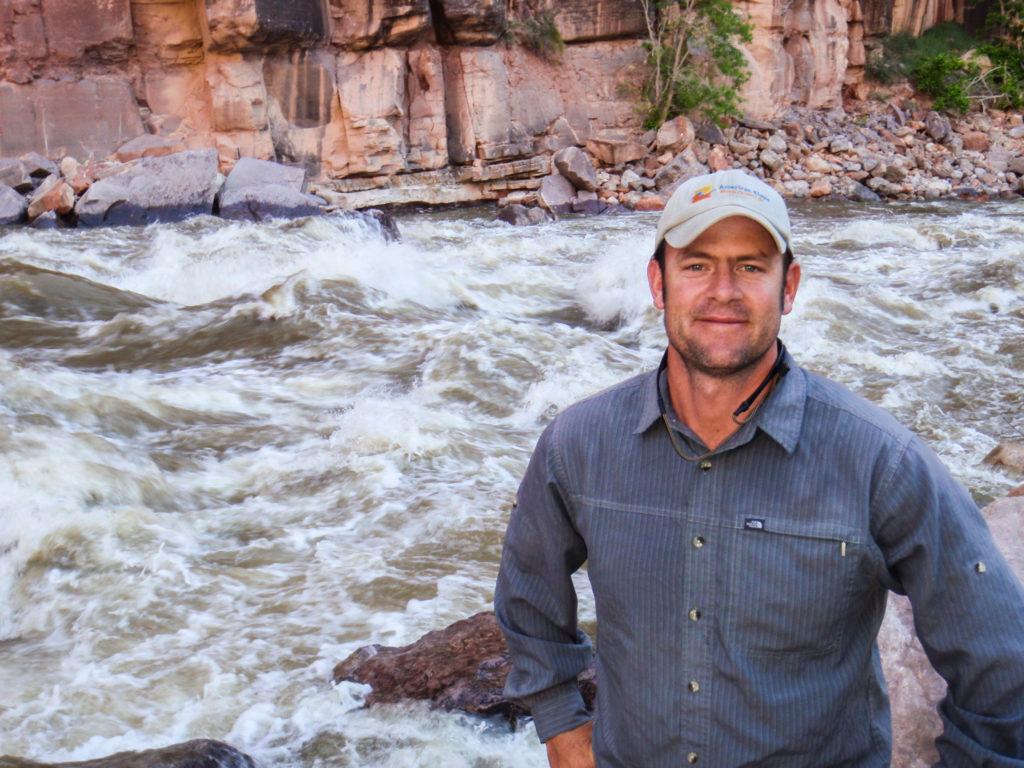

(Nathaniel Minor/CPR News)

Kevin Scannel, a fishing guide at Devil's Thumb Ranch near Tabernash, Colorado, shows off bug life taken from the Fraser River on Thursday, Sept. 29, 2016.

Colorado’s economy depends on water: where it is, where the people who need it live and work, who has rights to it. Fights over those needs are a core part of the state’s history, and they tend to follow a pattern. So in some ways, the fight over the Fraser River in Colorado’s Grand County is familiar.

Denver Water holds unused water rights on the river, which starts in the shadow of Berthoud Pass and courses down the western side of the Continental Divide past Winter Park, Fraser and Tabernash to join the Colorado River outside of Granby.

The agency, looking at the booming population and economy in Denver, now wants to exercise those rights. That means taking more water from the river, piping it under the Indian Peaks and sending it into Gross Reservoir near Boulder.

Some conservationists and environmental groups are crying foul, saying that the river has already been overtaxed (about 60 percent of its existing flow is already diverted to slake Denver’s growing thirst) and it’s time to let the river alone.

(Nathaniel Minor/CPR News)

U.S. Route 40 winds down Berthoud Pass and into Colorado's Grand County on Thursday, Sept. 29, 2016.

But the fight's pattern is taking some unfamiliar twists and turns. Influential groups like Trout Unlimited and American Rivers, who’ve historically fought diversion projects, support this one. In exchange, Denver Water says it will will help protect and enhance what’s left of the Fraser River.

That compromise has fractured traditional lines in Colorado’s conservation and environmental advocacy community, and fostered new alliances. While these organizations more or less agree on their ultimate goal -- to protect and restore the environment -- the strategies they use are very different. The big question that divides them: When to compromise?

Denver Water Extends An Olive Branch

Decades ago, environmentalists were not at the top of list of Denver Water’s concerns when it would try to build dams and add capacity. In the 1980s, environmental groups pushed back on a huge proposed dam called Two Forks.

“[Denver Water] told us in so many words: ‘We're the experts. You're little environmentalists. Get out of the way,’ ” Dan Luecke, then head of Environmental Defense Fund's Rocky Mountain office, told High Country News in 2000.

Then, in 1990, an EPA veto torpedoed the project at the last minute.

“That was really a turning point for our organization,” said Kevin Urie, a scientist who’s worked for Denver Water for nearly 30 years. “I think we realized with the veto of Two Forks that we needed to think about things differently."

He believes that while Denver Water has long taken environmental impacts into consideration with its plans, it didn’t engage with local stakeholders -- like conservation and environmental groups and Western Slope governments -- until after the Two Forks project died.

There’s a demographic change underway as well: Many of the Denver metro area’s new residents also want to play in Western Slope rivers on the weekends. That has pushed Denver Water leadership to put a larger emphasis on environmental stewardship, Urie said.

But all those new residents still need water. Denver Water delivers water to about 1.4 million people across the metro, about double what it did some 60 years ago. Conservation efforts have kept overall demand relatively low in recent years. But with more people moving to Denver every day, Denver Water expects its demand to rise 37 percent by 2032 from 2002 levels.

The Fraser River is key to Denver Water’s plan to head off a shortfall in the relatively near future. The agency wants to divert half of the remaining flows from the Fraser and its tributaries through the Moffat Tunnel to Gross Reservoir near Boulder. (The proposed expansion of Gross has started its own fight, which CPR News’ Grace Hood chronicled last month.) It would be treated at the agency’s plant in Lakewood, and eventually delivered to customers across the metro.

The agency expects to have all of its necessary permits by 2018 and construction could begin in 2019 or 2020. But to get those permits, Denver Water has agreed to be part of a group that includes Grand County officials and environmentalists called “Learning by Doing.” These different players are often at odds when it comes to water issues.

Urie said Denver Water’s participation shows its desire to do right by the environment and local stakeholders. They’ve helped fund an ambitious project that will engineer the Fraser River's flow on a nearly mile-long stretch between Fraser and Tabernash, squeezing it to make it narrower, deeper and colder -- and thus healthier.

(Nathaniel Minor/CPR News)

But is that what’s best for the river?

Urie thought about that question for a minute, and then chose his words carefully:

"Clearly the system would be better if we weren't using the water resources for other uses. But that’s not the scenario we are dealing with,” Urie said.

Trout Unlimited Sees Opportunity

(Nathaniel Minor/CPR News)

Kirk Klancke, president of the Colorado River Headwaters Chapter of Trout Unlimited, flashes a smile as he fly fishes on the Colorado River near Kremmling, Colorado on Thursday, Sept. 29, 2016.

The Fraser River project’s biggest booster is Kirk Klancke, president of the Colorado River Headwaters Chapter of Trout Unlimited. For him personally, it’s a way to help a river that he’s lived near and played in for 45 years.

"I can't talk about it without getting all emotional. My life's been spent on this river,” he said.

He sees it as a chance to restore a part of the river popular with anglers called the Fraser Flats. Here, the brush-lined river levels out after tumbling through the pine forests of Berthoud Pass.

His playground is popular with others, too. Grand County is a short one- to two-hour drive from Denver. From fly fishing to alpine and nordic skiing to snowmobiling, it’s a tourist-based economy. And in Klancke’s eyes, all of that rests on the health of its water.

He's watched the river dwindle and get warmer as more water has been pulled out of it. And that's changed how his family has used it. When his children were young, they could stay in the river for only a minute or two.

"They'd come out and their lips would be purple and they'd be squealing,” Klancke said. “Now I throw my grandchildren in the river and they're not in a hurry to get out. We spend up to an hour in a pool in the river."

He's watched this river that means so much to him get sicker and sicker; warm, shallow channels aren’t suitable for native fish and bugs. For years, he blamed the deteriorating environment on the Front Range and its water managers.

(Nathaniel Minor/CPR News)

Kevin Scannel, a fishing guide at Devil's Thumb Ranch near Tabernash, holds a caddis fly in his hand on Thursday, Sept. 29, 2016. Caddis flies and other aquatic bug life can only survive when water temperatures are cold.

"I was a little radical because I urinated in diversion ditches. It's about all I knew to do. I've matured quite a bit since then," he said.

His turning point came when he got involved with Trout Unlimited.

"I loved their approach,” he said. “They were able to look at it in someone else's shoes, which is what all mature people do. And then, move forward with opening up conversation."

Such conversations are what led to the Fraser Flats project, Klancke said. When flows are low, like they were this fall, the river is shallow as it stretches across its native bed. The new channel will allow the river to recede and stay deeper -- and cooler.

Essentially, that stretch of river will be turned into a creek. On its face, downsizing a river doesn’t sound like a big victory for environmentalists. But that's not how Klancke looks at it. During peak flows in the spring, Klancke points out, the river will be nearly just as wild as it is now.

(Nathaniel Minor/CPR News)

Kirk Klancke, president of the Colorado River Headwaters Chapter of Trout Unlimited, fly fishes on the Colorado River near Kremmling, Colorado on Thursday, Sept. 29, 2016.

And moreover, Denver Water has to stay involved in the Learning by Doing group. So if environmental issues arise down the road, Klancke said the agency will be there to help solve them.

Is it a compromise? Yes, Klancke admits. But water managers own water rights in the upper Colorado Basin that they'll use -- with or without his blessing. The right to divert water for “beneficial uses” is enshrined in the Colorado Constitution.

“We have to face reality here,” Klancke said. “There is no more mighty Upper Colorado. There's only keeping what's left healthy."

WildEarth Guardians Stakes Out Moral High Ground

(Courtesy Jen Pelz)

Jen Pelz, wild rivers program director for WildEarth Guardians, on the Rio Grande in New Mexico.

Like Klancke, Jen Pelz, wild river program director for WildEarth Guardians, has had her own evolution in thought toward environmental causes. Earlier in her career, she was a water lawyer in Denver who represented clients like the city of Pueblo that were taking water from Western Slope rivers.

But eventually she felt a pull toward environmental advocacy. Pelz credits that with childhood days spent on the banks of a tributary to the Rio Grande in New Mexico.

"It was kind of the place that I could go just be myself,” she said. “I developed a really strong connection to the river there."

She was drawn to the confrontational, no-holds-barred approach used by WildEarth Guardians. The group is known for its headline-grabbing lawsuits. Most recently they sued the federal government over haze in Western Colorado and leases to coal mines.

The approach seems to be working, at least by WildEarth Guardian’s measure. The haze lawsuit ended in an agreement where a coal mine and coal-fired power plant in Nucla, south of Grand Junction, will shut down in the next six years. A power plant in Craig, Colorado will shut down one of its units too.

“We're willing to not be liked by the general public, or by particular industries,” Pelz said. “And I think it takes that kind of moral integrity and just knowing where you stand on the issues, to really push the envelope."

(Nathaniel Minor/CPR News)

The Continental Divide, seen from Colorado's Grand County.

Pelz is not interested in compromise on the Fraser River. She faults Trout Unlimited for starting negotiations at the wrong place. In her view, the baseline shouldn’t be where the river is now with about 60 percent of it being diverted. The conversation needs to start with the river at its natural flows, she said.

"The harm has already been done,” Pelz said.

If the Fraser River is going to be saved, she says, it'll happen by letting more water back into the river -- not by taking more out. As the climate warms, she says the river will need all the help it can get.

“Let's start dealing with it now. Let's have that hard conversation now, not 50 years from now when there's no water left to have a conversation about,” she says.

Pelz says her organization, and another group called Save the Colorado, are considering litigation once final permits are approved. That could happen in 2018.

Such tactics doesn’t make Pelz a lot of friends. She said she's been ostracized from her former clique of water lawyers. It's hard for her to get meetings with government regulators.

WildEarth Guardians’ relationship with the greater environmental community is similarly strained. She said Denver Water is more willing to meet with environmentalists now because they've softened. And she's upset with what Trout Unlimited has become in the eyes of regulators.

"Trout Unlimited has been deemed by Denver Water and the state of Colorado as being the environmental voice,” Pelz said. “They get invited to the table because they have this role in communities, which I don't think is a bad thing, but they don't necessarily represent all of the different interests in the environmental community.”

As a result, she said, groups like hers are being left out of the conversation.

“They don't talk to us. They don't ask us what we think. And I've called them. And I've had meetings with them. I've asked them what they think. And they've told me they don't like our approach. And I understand that. But I think that it works both ways."

Pelz said it can be hard to be out “towing the left line.” Everybody likes to be liked, she said. But she's decided that over the long run, her methods are what will make a difference. To do anything else would be surrender.

“I don't want to have to explain to my kids that I gave up the fight for this river that is the namesake of our state, the state they were born in, because I was willing to compromise,” she said. “We may not win, but damn we are going to try."

American Rivers Finds Room To Maneuver

(Courtesy Matt Rice)

Matt Rice is director of American Rivers' Colorado River Basin Program.

When Matt Rice, Colorado River basin director for American Rivers took the job a few years ago, he made the decision to put aside his dreams for what he really wanted. Instead, he focuses on what he thinks he can actually pull off.

"In a perfect world, I'd like to see all the wild rivers in this country and in this state flowing freely and filled with fish, doing what rivers should do,” Rice said. “It's not realistic."

But he acknowledges that groups like WildEarth Guardians can make his job easier at times. When Guardians files a lawsuit and makes a bunch of people mad, a group like his can step in and talk with state regulators and businesses. Guardians essentially provides cover for groups closer to the political center, he said.

“Their advocacy pushes everybody, not just conservation organizations, kind of further to the left. And I think that's good,” Rice said.

But there’s a downside. Lawsuits and sharply worded press releases can sting, and are not easily forgotten. And Rice worries that aggressive tactics from far-left groups lead to skeptical parties like ranchers or Front Range water managers lumping all environmentalists together.

“That has the potential to undermine the progress we're making,” he said.

Looking To The Future

With the publication of last year’s Colorado Water Plan, a first for the state, officials are trying to turn the page on Colorado’s long fight over water. The plan, which officials describe as a roadmap to sustainability, stresses collaboration between competing interests and conservation of the increasingly precious resource.

“Now is the time to rethink how we can be more efficient,” Gov. John Hickenlooper said at the water plan’s introduction in November 2015.

Diverting more water should be the last-possible solution, Hickenlooper said. That’s welcome news to environmentalists like Matt Rice of American Rivers.

Rice said they are supportive of the Fraser River diversion plan for the same reasons Trout Unlimited is, though they aren’t part of the Learning by Doing group. But he hopes the Fraser diversion, and another major project in the works called Windy Gap, are the last trans-mountain diversion projects.

There just isn't enough water on the Western Slope, he said. And if another one comes up, Rice said they'll fight it with everything they have.

“We're kind of at the cliff right now in the Colorado River Basin,” he said.

Collaboration and compromise will certainly be part of environmentalism’s future in Colorado. But as groups like WildEarth Guardians continue to find success in the courts, the advocacy ecosystem has room for other strategies too.