Richard Dash of Alumina Energy stood in front of a small crowd gathered inside the white, marble hallways of the Colorado Governor’s Residence. This was his chance to pitch oil and gas executives on his company’s thermal storage system to capture energy from renewable or fuel-fired power plants.

Dash was among entrepreneurs from 13 companies in Denver for the Oil And Gas Cleantech Challenge, an annual event to gather ideas to reduce the environmental impact of the fossil fuel industry.

Before he could even begin, a young woman in black dress stepped in front of the podium.

“There’s no such thing as clean oil and gas!” she shouted.

“There’s no such thing as clean oil and gas!” answered other activists embedded in the audience.

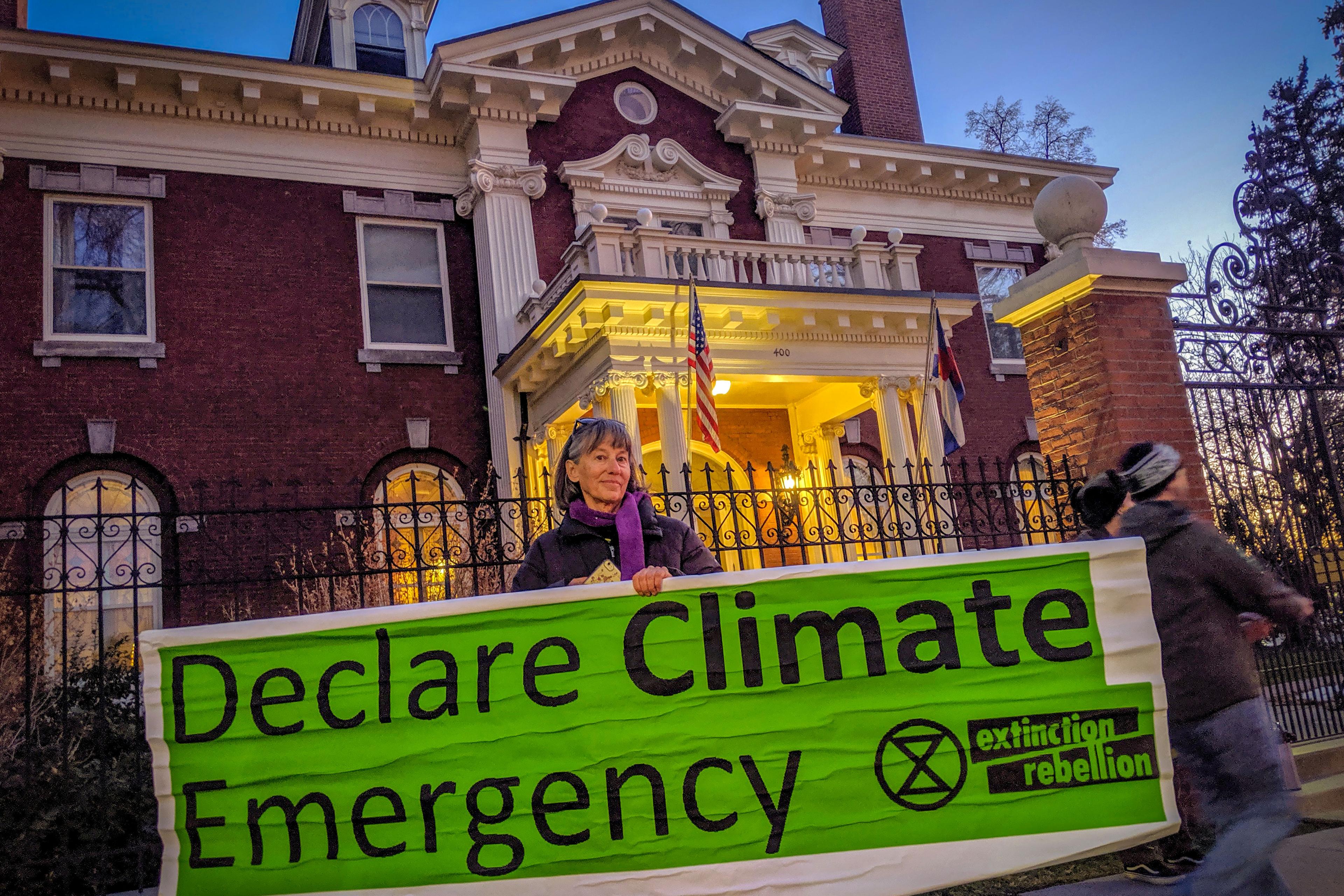

Many of the demonstrators were with Extinction Rebellion, a global movement advocating direct action to force people to confront the climate crisis. Some of the same activists were behind other recent efforts to disrupt government meetings and block traffic in Denver.

During their call-and-response disruption, the demonstrators declared the event a public relations sham designed to make oil and gas appear compatible with a livable climate. Over the course of an awkward minute and a half, they argued the planet didn’t need “cleantech” in the fossil fuel industry, but a rapid shift to different forms of energy. Security guards eventually removed the demonstrators.

A similar debate is playing out across the globe. As the climate warms, oil and gas companies hope to enlist novel technologies to cut methane emissions, generate power and even scrub carbon from the atmosphere. Climate activists counter that those efforts aren’t about protecting a safe climate so much as the profitability of the industry’s current investments.

“How dare you pretend that this can be solved with just 'business as usual' and some technical solutions?” 16-year-old climate activist Greta Thunberg said at the U.N. Climate Action Summit in September.

Shelly Curtiss, executive director for the Colorado Cleantech Industries Association, was rattled after the demonstration. Her organization had rented the space for the event for the last six years. This was the first time it drew any sort of controversy.

“It’s uncomfortable to feel like you’re getting called out when you feel like we’re doing the right things for these companies,” she said.

Curtiss added the CCIA believes the transition to renewable energy requires connections between all kinds of energy interests. The event’s sponsors included fossil fuel companies like ConocoPhilips and Nobel Energy, the nonprofit Rocky Mountain Institute, which promotes renewable energy, and the Colorado Energy Office, which aims to lower the state’s greenhouse gas emissions.

Those sponsors chose the presenters from a larger pool of applicants. The final competitors brought products for water management, pipeline leak detection, hydrogen fuel production and power generation from the pressure in natural gas lines.

All the technologies promise lower emissions. The question is what role those sorts of innovations might play in the larger struggle to confront climate change.

Rob Schuwerk, executive director for Carbon Tracker, North America, is skeptical. His group tries to tell investors which fossil fuel companies, if any, are aligned with multinational climate goals. While he welcomes any technology to reduce emissions, he said it doesn’t change a hard reality: companies need to stop extracting fossil fuels.

“You’re looking at a decline in production,” he said. “There’s almost nothing they can do that would prevent them from also reducing production.”

In a recent analysis, Carbon Tracker found seven of the world’s largest listed oil and gas companies would need to cut production by 35 percent to avoid driving temperatures 1.5 degrees Celcius above pre-industrial levels. It adds there little room for new extraction projections.

But, as entrepreneurs inside the event pointed out, that also means some amount of oil and gas production will be around for decades.

Dick Thompson is the CEO of Radical Combustion Technologies, LLC, the Virginia company that ended up winning the competition. His company offers a way to retrofit internal combustion engines to change how the machines ignite fule. Rather than using a flame or a spark, a chemical process kicks the engine into motion. The company claims the technology radically reduces emissions and increases efficiency.

Thompson said ideas like it are vital as the climate warms.

“100 years from now, there may not be any more need for fossil fuels,” he said. “But for the time being, we as a civilization have to embrace every new invention that allows us to live more healthy lives.”

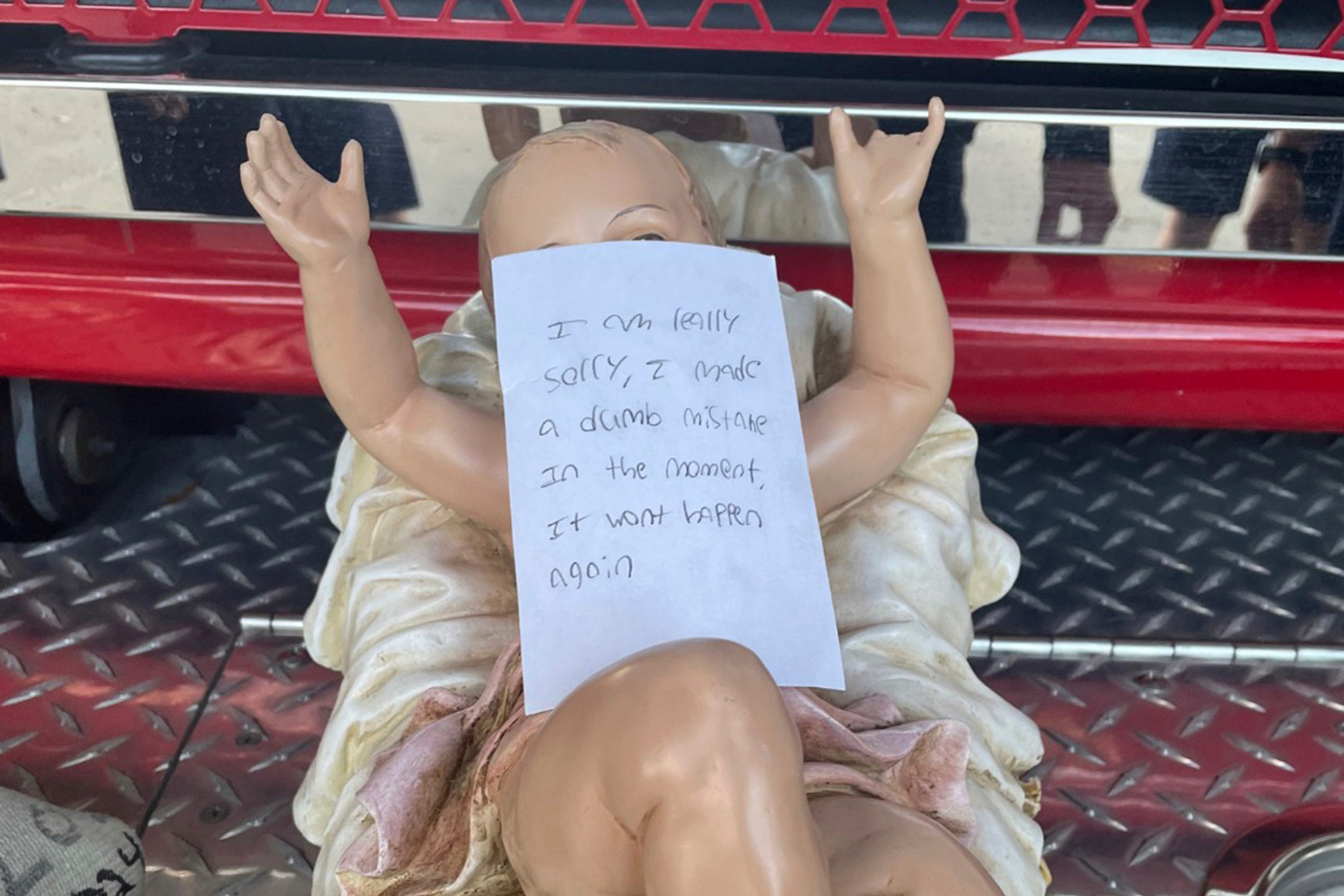

While the event continued inside, the demonstrators joined other activists on the sidewalk outside the mansion. The group projected a logo for Extinction Rebellion on the side of the building.

Many of the signs took aim at Gov. Jared Polis for continuing to allow oil and gas drilling in Colorado. While Polis had an option to live in the mansion, he instead chose to stay in his home in Boulder. The CCIA went through the regular application process with the state to hold the event in the residence.

Still, Devon Reynolds, the woman who led the interruption, said it was appropriate to target the governor since the Colorado Energy Office sponsored the event. A graduate student in Environmental Studies at the University of Colorado Boulder, Reynolds said she knew many of the companies inside were trying to do the right thing, but she thinks there’s no time left to fix the fossil fuel industry.

“Climate change is happening now,” she said. “It's no longer acceptable to talk about bridge fuels or something like clean oil and gas, which is something we could have done 30 years ago, but is no longer an option.”

She said if the companies really want to make a difference, they should invest in just, sustainable forms of energy, not technology to keep their current business models alive.