Greg Meyers moved to the town of Lyons shortly before the 2013 flood devastated the community. Living through that disaster meant the Boulder County native got to know people quickly; it brought everyone together and forged a strong bond that still shapes the small foothills community today.

“There’s a lot of people that I love in that town,” said Meyers.

However, since the killing of George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter protests that have spread across the nation, Meyers, who is Black, has sadly concluded that, for all its wonderful points, Lyons is also “the most racist town I’ve ever lived in.”

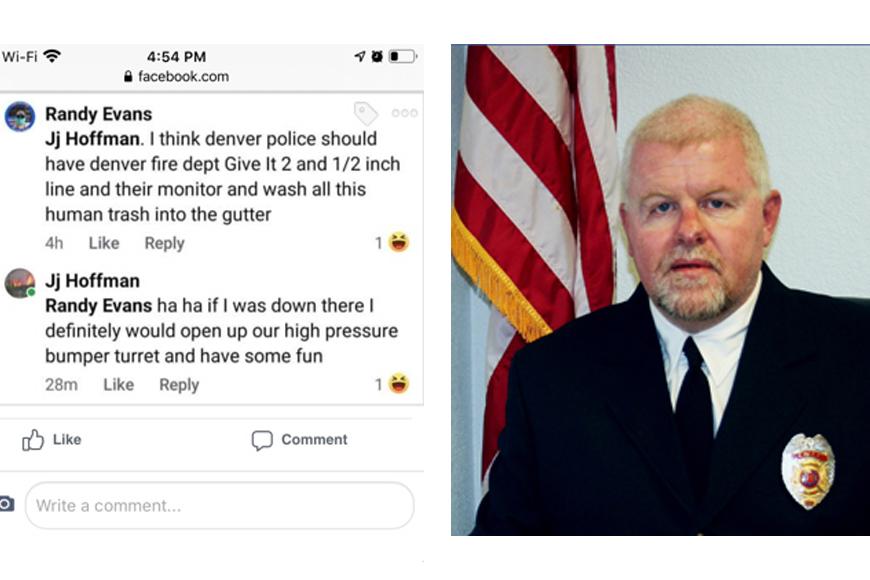

Meyers spent the summer feeling isolated after he pushed back against remarks Lyons’ then-fire chief JJ Hoffman made on his personal Facebook page about protesters that many, including Meyers, felt were racist. Hoffman, who is white, resigned in June, after the first post was made public, but the controversy has continued to ripple through Lyons.

Many people back the long-time fire chief and feel he was quickly judged and unfairly condemned. Others believe community leaders have not adequately addressed what happened or the fight for racial justice unfolding across the country. How the situation played out is one of the reasons Meyers decided to move away from Boulder County for the first time in his life, to a more racially diverse part of the state.

While Colorado’s largest marches and protests against police brutality have happened an hour south in Denver, they’ve exposed fault lines in Lyons, a mostly white town of around 2,000 people.

“There was no statement from the town, no statement from the mayor [about the fire chief’s post]. I feel like their lack of action said something in and of itself,” Meyers said.

The Lyons Fire Protection District covers the town and some surrounding communities. Its firefighters are almost all volunteers, but Hoffman was paid. The board issued a statement in early June, before his resignation, saying it accepted Hoffman’s apology but would formally reprimand him for his “insensitive remark.”

The district put out another statement later in the summer when an online comment from the interim fire chief surfaced that also appeared to deride protesters. In that instance, the district defended the interim chief, saying his comment was misinterpreted. The fire district did not respond to CPR’s request for comment.

Lyons’ mayor Nick Angelo acknowledged that the chief’s resignation has split the community and said he wants to hold a public forum when things settle down to try to alleviate tension. He said he will use his own money to hire an outside mediator to educate people in Lyons about what it’s like to be Black in America in 2020.

“I hope that we can come together as a community again,” said Angelo, who has lived in Lyons for three decades. “The saying that we used after the flood was ‘Lyons strong.’ And I just hope that we can achieve that again: have respect for one another, tolerate one another… Since we don't have a large, or hardly any, African American population. It's very difficult for all intents and purposes, [as] privileged white people to understand the Black experience in America. It's impossible.”

According to the Census Bureau’s most recent American Community Survey, Lyons is 88 percent white, while 2 percent are Black. Overall, just 1 percent of Boulder County’s population is Black, according to the State Demography Office.

The largest protests against police brutality and racism have been concentrated in big cities. But their impact extends far beyond those racially and ethnically diverse urban areas, to communities where racial disparities haven’t taken the center stage before. In recent months, rural communities like Gunnison and Rifle have hosted Black Lives Matters protests.

The Lyons Social Justice Committee continues to host protests every Sunday against police brutality. While demonstrations in Lyons have been peaceful, dealing with issues around race in practical everyday life can be messy.

A Facebook comment with lasting consequences

In late May, Hoffman joined a Facebook thread on his personal page criticizing protesters. After another person commented that Denver Fire should turn its hoses on the demonstrators, Hoffman replied: “ha ha if I was down there I definitely would open up our high pressure bumper turret and have some fun.”

Meyers was the first person to publicly raise concerns; he posted a screenshot of Hoffman’s message in a different Facebook group for current and former Lyons residents. It’s a place to air concerns on a range of topics; everything from bear proof garbage cans to vaccines, and a lot of people check the community forum daily.

Meyers said his mother grew up in the south during the Jim Crow era and the height of the Civil Rights movement and his teenage son had been at the protests in Denver that weekend. Along with Hoffman’s post, Meyers added an image of what it called up for him: high-pressure hoses being used against demonstrators in Birmingham in 1963. Meyers said he was aware that by speaking out, and adding the image, it might ruffle feathers and upset some people in Lyons.

“I knew I would pay a price.” But he said when he thought about what he would say to his own children, he knew the cost was worth it. “Nothing would have bothered me more than doing nothing,” he said.

While a lot of people sent him words of encouragement and posted similar concerns, he said others took Hoffman’s side immediately. Meyers said some people he considered friends printed “We love JJ” bumper stickers for their cars. Signs supporting Hoffman were outside near the fire station in downtown Lyons for weeks.

Hoffman did not return CPR’s request for comment. In his initial apology, he said he was sorry if he offended anyone and he wasn’t trying to “belittle history,” but was upset when protests turned to “riots.” In his resignation letter, Hoffman said his “thoughtless remark” reflected poorly on the district and himself.

Meyers said he was even angrier and discouraged when weeks after Hoffman resigned screenshots of additional private Facebook comments became public that showed Hoffman participating in conversations that were broadly critical of protestors.

“I personally don't want to focus on what exactly happened, but I want to focus on, what do we do now?” said Kerry Matre, the former president of the Lyons Fire Fund. She resigned publicly from the organization in protest of Hoffman’s Facebook comment but said she never expected him to step down himself.

“Whether it's an issue of leadership taking advantage of their position, or racial undertones that have definitely bubbled up in conversations, we need to figure out what's next and not just ignore it cause that's not going to help us.”

Matre would like the fire department to review and update its training policies and for the town to look at how it can be more inclusive.

She said it hasn’t been an easy time and she’s faced backlash for not supporting Hoffman, including from people who believe she brought the issue to the attention of Democratic state lawmaker Jonathan Singer and the Boulder County branch of the NAACP, something she denies doing. Matre said the situation has cost her friends, notably Hoffman, with whom she had worked closely.

She, however, stands by her decision and said a number of people reached out to thank her for speaking up.

“It is extremely hard on the people of color in the area,” Matre said, who is white. “There's so few of them. And I do know that the ones that I've spoken to feel very outcast from the town. This is such a great community and people come together and they help each other. But right now there's a group of people who feel not included... And, you know, we need to fix that, change that.”

Lyons united and divided

The 2013 flood changed the fabric of life in this town nestled near the mountains about 20 minutes north of Boulder. It took years to rebuild.

“It was the most solidarity that I've ever experienced in any community in my life,” said resident Kim Franco of that experience. In contrast, the discord over the fire chief is the most divided she’s seen people since voters defeated an affordable housing measure after the flood.

Franco considers the current situation “heartbreaking” and said she wishes people could be together. She lives a few blocks away from the fire station and frequently walked by the signs supporting Hoffman. She didn’t weigh in online but watched everything unfold.

“Something like COVID, we’re instructed to be apart, [which] makes it harder to have the conversations that we need to have to have this kind of solidarity,” she said.

Lena Cinnamon moved to Lyons a year ago with her husband, whose family has lived in the area for generations. Cinnamon grew up in Russia and is of Korean descent. She is among the small percentage of Asian American residents in Boulder County.

She’s supportive of the Black Lives Matter movement and has personally faced discrimination, especially during her childhood. But she stands behind the fire chief and wishes he had not resigned. She said Hoffman is beloved in this tight-knit community for helping people and for his role during the flood. He was the fire chief for more than a decade and she feels people outside of Lyons rushed to cast him aside without understanding the full picture.

“The flood played a big role in this community. It has changed a lot of lives. It affected a lot of people and [the] fire department — the core people in that scene that helped and did all kinds of things — and it saves lives. You know, they come and rescue people. It saved my family,” Cinnamon said.

A changing area

Lyons has experienced something of a population shift since the flood. The waters washed away a mobile-home park that was never rebuilt, erasing some of the town’s most affordable housing. In the years since, housing has only become more expensive, forcing out some long-term, but less affluent residents.

The changes have led to some resentment, and calls to preserve what makes this town special, but Meyers said those conversations can also feel tone-deaf. He points to a separate online discussion that unfolded around the same time as the controversy with the fire chief.

Someone posted an image of a sign from the Long Island, New York town of Montauk. “Respect Montauk,” it declares. “We should make these with ‘Lyons’ on them,” the post said, taking particular aim at newcomers who complain about music being played downtown. The sign continues, “You came here from there because you didn’t like there, and now you want to change here to be like there. We are not racist, phobic or anti-whatever-you-are. We simply like here the way it is and most of us actually came here because it is not like there, wherever there was.”

A lot of people “liked” the post but Meyers took a different view of it, responding, “So this sign is *actually* OK with you all? This is literally the kind of signage used to keep POC out of ‘sundown towns.’ I can’t believe how many of you think this is anywhere near acceptable.”

Ben Rodman, an acquaintance of Meyers who has lived in Lyons for 20 years, is disappointed with how the community has handled everything. He thinks it’s unfortunate the local conversation has started to die down as people focus on the broader national discussion and other concerns. To him, Lyons missed an opportunity to confront an important issue at the local level: racism.

He’s sorry Meyers moved away.

“What a shame. That we not just let him leave, we made him leave.”

Rodman, who is white, said the situation with the fire chief is especially complicated because in a small community everyone knows everyone else and firefighters deservedly garner a lot of respect for doing a dangerous, difficult job for little-to-no pay.

“This going to sound a little trite, given how much it's been in sort of the national dialogue recently, but I think we need to just reexamine our privilege and our preconceptions and our prejudices, and just understand how systemic and pervasive these kinds of attitudes are, and then reflect. As Americans, we recite an oath to uphold liberty and justice for all,” Rodman said.

For Meyers, he’s looking forward to building a life in Pueblo, where he's already closed on a new house. For the first time ever, he said, his neighbors are not white. He plans to continue his auto repair work like he always has, enjoy a slower pace of things and get familiar with an entirely new community.

“I’ll be spending less time worrying about racism and I’ll do what I want to do, and live my life as a human being. I don’t want to live where I’m pointed out as the Black guy. My whole life it’s been like that.”