On a winter weekend, Sara Lee peers through the library window at Woodland Park High School. She’s outside looking in — to the special place that she and her student library advisory board created. It’s filled with plants, couches and murals. It looks like a pathway of books in a forest.

But Lee can’t go back into her high school library. She was involuntarily transferred to an elementary school.

“I was devastated,” she said, her voice breaking.

Lee was that teacher who was welcoming to everyone, who makes that extra effort with a student who was feeling down or who needs that extra guidance to graduate. The kind of teacher who let kids watch World Cup soccer in the library during their lunch break — and made them popcorn when the U.S. played. Who encouraged the special education students to be in charge of taking care of the library’s plants. Who oozed positivity and excitement.

She ran into one of her students last night.

“Her face just fell and she said, ‘But what are we going to do without you?’”

Teachers in this small district northwest of Colorado Springs, like teachers across the country, are scared and uncertain about what they can and can’t say in school. A new national RAND survey shows many teachers are “walking on eggshells” in response to restrictions on how they can address race- or gender-related topics, or any other topics that appear controversial. They reported a “chilling effect” in their classrooms. Lee believes she was involuntarily transferred to an elementary school as a warning to other teachers to stay in line.

District officials declined to comment for this story.

Eighteen years with the district, the last 11 at the high school, Lee did a bit of everything starting with teaching theater.

“We did some amazing productions,” she enthused. “It became my home. I would spend 16 hours a day here.”

She was the dean of students during COVID-19. She was the library media specialist. She developed an orientation program to welcome new “Panthers” to the school. She oversaw several of the school’s major tests. She advised a Sources of Strength class, a national suicide prevention program. Lee was also the unofficial person to make sure the school bulletin boards were full and colorful.

“I try to bring positivity to the school. My class did a lot of paintings in our building … Things like, ‘we believe in you to be the leader you are,’ ‘your life makes a difference.’ Sayings and writings that are very colorful are on our walls, making a real difference in the feel of the school overall.”

Now she worries about the students who will wonder why she’s not coming back.

Woodland Park is a tight, collaborative school district where teachers spot and support each other on a daily basis.

Lee said things in the district were going pretty smoothly until voters elected a new school board a couple of years ago. It billed itself as “conservative” and ushered in a charter school that was previously denied, a new policy on teaching controversial subjects and adopted the conservative American Birthright social studies standards. In Lee’s and other teachers' minds, three words describe how they’re feeling now.

“Targeted, threatened, and unsafe.”

This is at the same time employers are asking educators to make sure students have practiced “soft skills,” including navigating different viewpoints and opinions.

“Are they critical thinkers? Can they work in groups? Can they handle discourse?” said Lee, who tried to show students what they were learning mattered.

What happened to Lee?

So how did this happen to Lee, someone who is loved by so many students and effusive about her own love for the school? Did Lee cross a line or was she unjustly punished?

One day in the class this school year Lee advised, Sources of Strength, a student who sat on a school board committee asked her classmates for feedback on the candidate for interim superintendent. The students didn’t know anything about him. So, they asked Lee questions about the candidate, Ken Witt.

The district hired Witt Dec. 21 last year.

“I answered them to the best of my ability,” Lee said. “I encouraged them to go to the websites to look up the name of the sole candidate Ken Witt. I asked them, go home, please go home and talk to your parents. Ask your parents what they think.”

Lee gave them her opinion. She can be passionate. Teachers are allowed to do that. The kids started looking up Witt’s past in the Jefferson County district. He was board president there from 2013-15 when he’d tried to push controversial changes to the history curriculum. JeffCo students walked out at several high schools across the district. It drew national media attention. Eventually, Witt and two other board members were recalled in a rancorous election. The information made the students pause.

“They started asking, what can we do about this?” recalled Lee.

Lee said they had a frank discussion about free speech and the ways people have made their voices heard, from social media campaigns to walkouts. Woodland High students walked out of the school in favor of gun rights in 2018. The students asked their advisers to leave the room so they could discuss the matter on their own, something typical in Sources of Strength classes.

“I didn't want them to think that they had to say things that we agreed or disagreed with, right?” Lee said. “I wanted to give them the freedom to continue the conversation without the adults in the room.”

A student who was at the meeting confirmed Lee’s account of what happened.

“The advisers gave them facts and a little bit of their general opinions, keeping in mind that it was just their opinion, and they encouraged us to research on our own and make our own opinions,” said one student, whose parents allowed them to speak to CPR on the condition of anonymity.

A big part of Sources of Strength involves launching campaigns on issues that matter to students, whether it’s suicide prevention, bullying, or other matters that affect their lives in and out of school, said the student.

“We saw this as the same process as doing a “Sources” campaign, focusing on positive things, supporting our teachers, targeted messaging – who do we want to know? And we said we want the whole community to know. News stations were called and it came together within 24 hours,” said the student. Before making their decision public, everyone texted their parents for permission to do a walkout.

“We didn’t make the decision until after the adults were out of the room,” said the student. “We planned the whole thing. Really, I don’t think it’s fair that anyone else would be given credit for what we did.”

The bell rang, the students left.

Lee didn’t know what they’d decided. Following district policy on controversial topics that come up unexpectedly in class, Lee told her principal about the discussion. On Dec. 14, 45 minutes after a walk-in protest against Witt, Lee was placed on administrative leave. By the end of the day, Lee was cleared to come back, but with a two-page letter of reprimand.

The letter said she’d participated in unprofessional behavior and a lack of discretion. It said her passion in sharing biased personal information about Witt was inappropriate and insensitive. It said she didn’t follow district policy on teaching controversial issues in a way that students “feel free to form and express their own points of views.” It told her she couldn’t discuss the school board process or decisions with students.

The district passed a policy last year that gives the parents the right to opt their children out of controversial subjects, which is defined as “any problem, subject or question about which there are significant differences of opinion.” Among other things, it states that teachers can share their own opinions but don’t have the right to persuade students to their own viewpoints.

A school board member told the press that adults had manipulated the students — and were beneath contempt for doing so.

That made some students furious. They showed up to a board meeting that night.

“Adults are not instigating us. This is our say. We are our own people!” said one student at the meeting to cheers from the audience.

After the meeting, school board president David Rusterholtz promised the students a one-on-one interview with candidate Witt the following Monday. The students worked hard on their questions. They even had “in-text” citations. But that Monday, Rusterholtz visited the school and told the students it was inappropriate for students to interview Witt but said he’d try to ask their questions at a public interview that night.

And this is what got Lee in trouble a second time.

The students wanted to ask a specific question relating to an incident in Jefferson County when Witt publicly disparaged a student group and its leader, stating he wouldn’t associate with them. But the board president instead asked a generic question, one the students did not ask.

“How will they feel valued and not bullied by your approach of style or leadership?” he asked Witt, who answered the question.

At that point, Lee couldn’t contain herself. She calls out to the board president that he wasn’t valuing students by not reading their questions as written. She left the auditorium. The next day the district placed Lee on administrative leave again. For a month she had no word on her fate until mid-January when she learned she was being transferred.

Lee calls herself a ‘mama bear’ when it comes to her students

“There comes a time in everyone's life where there's a line. And when you misrepresent my students, when you lie to my students, that's my line. They crossed my line. They crossed it hard…because those young humans, this is their lives we're messing with. Nobody has a right to misrepresent them or lie to them or treat them like they're not important. And so, I will fight for them.”

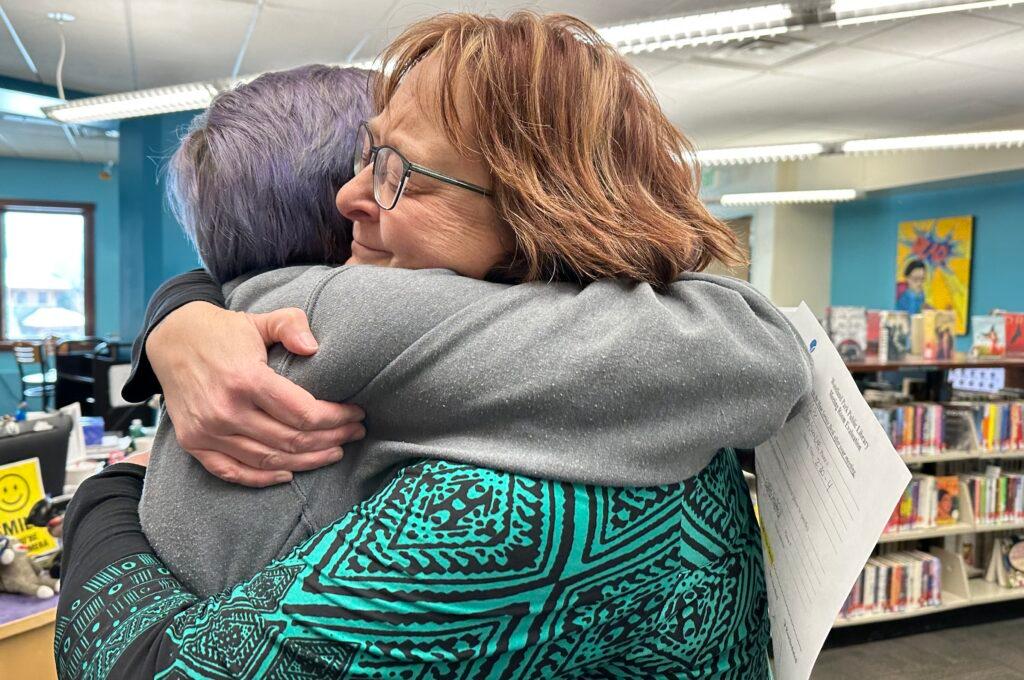

Lee has a hard time describing how much she misses her students and colleagues at the high school. Seeing them on the street, getting a hug in Walmart or chatting with a former student in the public library, makes her feel better.

She looks to her in-box in her phone, filling up with messages from former students. One reads:

“You inspired me in so many ways, loved me, and taught me to do hard things. I will never forget what you have done for me and how you have touched my life.”

And another:

“Sometimes I felt so alone but then I remembered I had you on my side no matter what.”

She’s grateful she had a tiny role in helping them become who they are.

“I hope I've touched some lives, so that when they are, 10 or 15 years away, they can look back and say, that person saw me. That person believed in me. That person gave me space to be me.”

The Woodland Park teacher’s union has filed a formal grievance on behalf of all member educators, alleging retaliation against Lee and arbitrarily reassigning her without due cause. It alleges that’s had a chilling effect on teachers who want to be able to have open dialogue without fear of retaliation, it said.

Correction: This story has been updated to correct a quote from one of the members of the Woodland Park District school board. The board member told the press "that adults had manipulated the students — and were beneath contempt for doing so."