A report released today aims to quantify the historic loss of life, land and precious resources for 10 Native nations historically in Colorado, and asks the state to help “mend all that has been broken between Colorado’s original inhabitants and the settler community.”

The privately funded study took two years to complete and is over 700 pages long. It draws on treaties, governmental records, scholarly works, magazines, journals, newspapers, and other sources. It calculates the total market value of dispossessed land at $1.17 trillion.

“My role in this is to try to find the truth about what happened to Indians in Colorado,” said Rick Williams, who helped spearhead the project. He’s Oglala Lakota and Northern Cheyenne and chairs the Truth, Restoration, and Education Commission (TREC).

“We don't want to alienate anybody. We just want people to think about that this is somebody else's homeland.”

He said a driving factor behind this research effort was to have as much history as possible in one place. The origins of the project date back to 2021 when it became clear that for over 150 years, the official language used to start the Sand Creek Massacre was never revoked, even after Colorado achieved statehood.

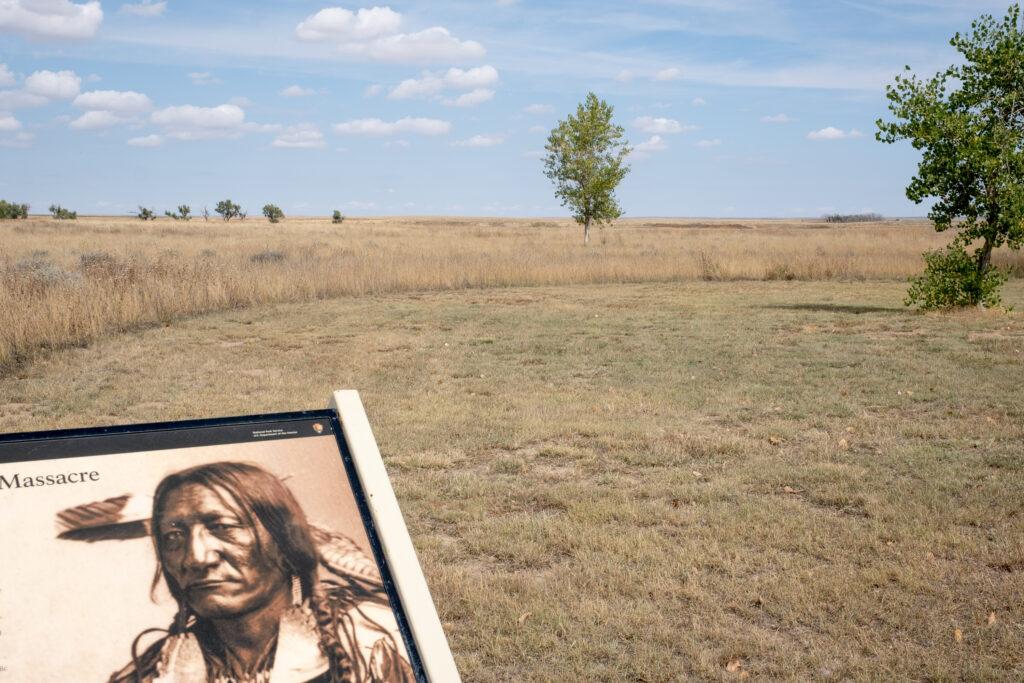

It’s one of the most notable incidents of violence against Native Americans in the history of the West. More than 200 Cheyenne and Arapaho people, mostly women and children, were killed at Sand Creek in an unprovoked attack by the American military, in part of a campaign across the region to kill Indigenous people and cultures.

After that discovery, Gov. Jared Polis officially rescinded the proclamations at the Colorado State Capitol.

The new report goes far beyond the Sand Creek Massacre. The goal is to foster dialogue and provide resources for tribes and state leaders. It also asks Colorado for reparations and to restore some of the state’s public lands and hunting and water rights back to the tribes.

“It would be really wonderful to have the Colorado state government announce that they're going to recognize welcoming back the nations that were alienated and helping them recover and restore in their homeland. Wouldn't that be a wonderful thing? That's all we want,” said Williams.

The proposal is for a 0.1 percent fee on new real estate transactions that would be distributed to the tribes depending on where the transaction occurs. The tribes that could get money under the proposal include the Apache of Oklahoma, Cheyenne & Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma, Comanche, Kiowa, Northern Arapaho, Northern Cheyenne, Eastern Shoshone, Ute Tribe of Utah, Southern Ute, and Ute Mountain Ute.

It also recommends that the U.S. Congress and the state resolve an illegal land transfer related to the Fort Wise Treaty of 1861 by restoring part or any of the land to the Northern Cheyenne or the Northern Arapaho.

“We're not going to ask any person that has private property to give up any land,” said Williams. “That would defeat the purpose because our people understand what it was like to have to give up their land and move away. And we never want that to happen to anybody else.”

In recent years the state has taken action to start to reconcile with its historical treatment of Indigenous people. In 2014, then-governor John Hickenlooper officially apologized for the Sand Creek Massacre; the state is constructing a memorial; and has undertaken efforts to get rid of offensive school mascots and rename mountains that carry the names of people who terrorized tribes.

Williams said none of that goes far enough to account for the way Indigenous people were murdered and forcibly removed from Colorado. For example, he points out that there is no reservation land on the Front Range, even though it was promised to tribes.

However, many of the report’s proposals would need legislative approval. The first step is likely trying to work with the legislature’s bipartisan American Indian Affairs Interim Study Committee that is meeting this summer and fall.

Democratic Sen. Jessie Danielson sits on the committee and is arguably the legislature's biggest advocate for the Native community. She sponsored a number of laws over the years including an office for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Relatives, and a law that allows American Indian graduates to wear traditional regalia to celebrate.

Danielson said she has not read the report yet but plans to. She has long said lawmakers need to pay more attention to these issues, and that one challenge is the lack of representation at the statehouse.

“I work on issues facing the Indigenous community," said Danielson, who is not Native herself. "We've only ever had one Native person ever serve in the legislature in the state of Colorado.”

Terri Bissonette grew up in Colorado and is a member of the Gnoozhekaaning Anishinaabe tribe. She also worked on the report. She said throughout her life she’s constantly had to answer questions about whether there are any American Indians living in Colorado.

“We feel like we've been rendered invisible here, and we believe that that's not by accident,” she said.

The report asks the state and the City of Denver to collaborate on constructing an American Indian Cultural History Center. This center would house offices for any tribal nation that ceded land in Colorado and function as an information hub. Williams’ organization, People of the Sacred Land, is also working on a school curriculum based on the TREC’s findings.

Bissonette wants every Coloradan to know and understand the state’s history, and more importantly, she said, to understand that the historical trauma their ancestors experienced continues to manifest itself today.

“We are at the top of every bad statistic. We are at the bottom of every good statistic. And it repeats itself year after year after year,” she said.

Williams added, “How do we create a better future for our people? And how do we make ourselves so we're not invisible anymore? Why is it, are we an afterthought? We're only recognized when we dance. It’s kind of sad.”